HE may have been the greatest dancer on Earth, but Fred Astaire really wanted to be the man who wrote the songs that made us dance.

This year marks six decades since Astaire appeared in the first-ever TV show recorded in colour – and it was far from the only historic event in his remarkable life.

Born in Nebraska in 1899 and dying aged 88 in Los Angeles in 1987, Fred shone as a dancer, singer, actor, presenter, choreographer and even percussionist.

He would marry twice and have two children and he became one of the planet’s most recognisable faces. But for most of those 88 years, he wished he could be just a songwriter!

In some ways, Astaire was a man of great contradictions – a conservative who hated the permissive, promiscuous Seventies but also a “silly kid”, breaking his wrist while skateboarding at the age of almost 80.

He loved daft schoolboy jokes and his friend David Niven called him “a timid pixie”.

He was also capable of deep passion, pursuing his first love until she finally married him and was then unable to get over it when she died after 21 years of blissful marriage.

A devoted dad who would regularly dance down the stairs in the morning, just to delight his kids, Fred and Ava, he was also a fashion icon into his old age, wearing old ties or scarves instead of a belt, and much-copied for his elegant style.

Although he would become one of the greatest superstars of all time, and influence dance like nobody before or since, Fred was also deeply modest about his talents and reputation.

“I just put my feet in the air and move them around,” he would insist, when they tried to give him a big head with their compliments.

As time went by and even he could see that he really was special, he became even more self-effacing, insisting, “The higher up you go, the more mistakes you are allowed. Right at the top, if you make enough of them, it’s considered to be your style.”

In time, he did master the songwriting thing, putting the music to Johnny Mercer’s lyric for I’m Building Up To An Awful Letdown, which made No 4 in the 1936 Hit Parade.

He also recorded his own material, such as It’s Like Taking Candy From A Baby, with Benny Goodman – but it would be for his dance and acting, and his real-life reputation as one of the business’s genuine good guys, that he will be best remembered.

Fred, of course, had recognised this by the time of his passing. Not long before he died, he acknowledged that Michael Jackson was the biggest thing in popular dance at that time. “I didn’t want to leave this world without knowing who my descendant was. Thank you, Michael,” Fred said of the man who brought us the Moonwalk.

One reason that Fred Astaire’s image has never been tarnished since his death is down to certain powers he made sure he had, even beyond the grave.

Often approached for permission to portray him in film, Fred always said no. He then had a clause inserted in his will to prevent it from ever happening.

“However much they offer me, and offers come in all the time, I shall not sell,” he revealed, saying of the clause, “It is there because I have no particular desire to have my life misinterpreted, which it would be.”

What a life it was!

He was born to Johanna and Frederic Austerlitz, an American and an Austrian. His father had come from Linz and his parents had converted from Judaism to Catholicism.

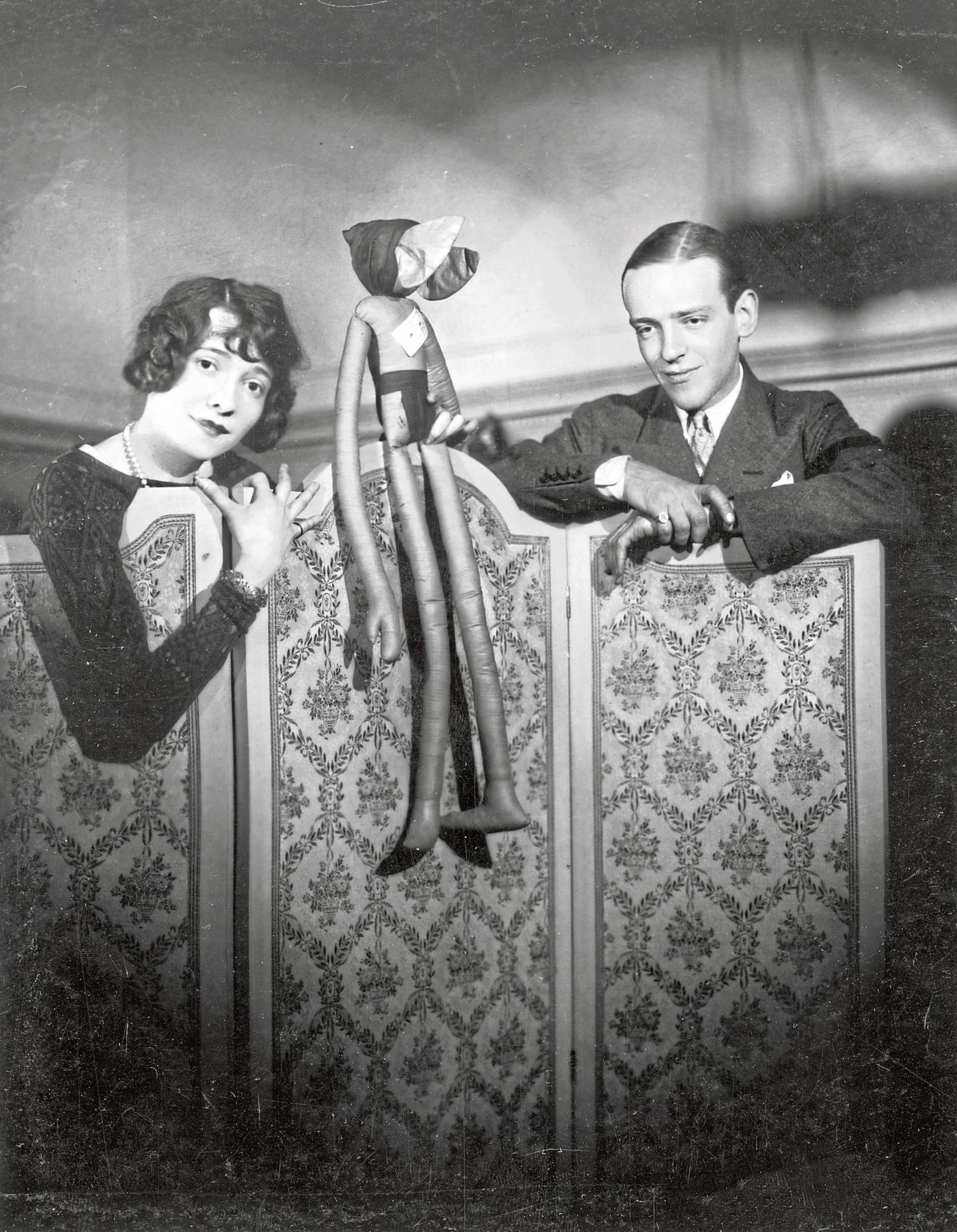

The young Fred’s sister, Adele, born a few years before him, showed signs of being a brilliant natural dancer, and the two of them were still kids, barely school age, when they began entertaining together.

Adele, who would propose to and marry lord Charles Cavendish, son of the Duke of Devonshire, was vivacious and showy, and her brother picked up every dance trick he could by watching her.

As you can imagine, there was more than an element of competition between the siblings, too, but in later years would claim that they agreed she had the talent and he had the strength.

It was actually in these formative years that their own mother suggested the name Austerlitz was wrong for them – it sounded like the name of a battle, she said, so why not try Astaire?

The story goes, though nobody is quite sure, that there had been an uncle by the name of l’Astaire, but wherever it came from the new name stuck and did rather well.

A bit less interesting was the name of their first act together – Juvenile Artists Presenting An Electric Musical Toe-Dancing Novelty doesn’t have a great ring to it, really.

It did, however, feature Fred in top hat and tails in the first half, an outfit the world would grow used to seeing him in. Some believe that Fred took to wearing the top hat to make him look taller, as his big sister towered over him.

For the second half, though, he wore a lobster outfit!

If it was all a bit childish, they clearly could dance, and local papers reported positively on these early shows, one even dubbing them “The greatest child act in vaudeville.”

Height, however, really was getting to be an issue. The brother and sister were becoming laughably different in size.

Although their father had convinced some serious venues to give his kids a chance, Adele was now shooting up in height and the family took the decision to temporarily give up on their shows until Fred added a good few inches and caught up.

After a two-year break that must have had Fred and Adele champing at the bit, they came back as if they’d never been away, Fred even writing music and organising all the songs for their shows. By the late 1910s, it was becoming clear to the siblings that Fred’s skills were outpacing his sister’s, and it was Fred himself who prepared the choreography so well that it wasn’t always obvious.

They even appeared together on Broadway in the Twenties, and in London. Their British shows included the Gershwins’ Lady Be Good in 1924.

By 1930, audiences on either side of the Atlantic could see that Fred Astaire was head and shoulders above everyone else, regardless of his height. One critic said in that year, “I don’t think that I will plunge the nation into war by stating that Fred is the greatest tap-dancer in the world.”

It was in ’32, when Adele fell head over heels for her Lord – it would be a tragic marriage – that Fred and his sister parted company. Lord Cavendish would die in his thirties of acute alcoholism and all three of their children would die shortly after birth.

Fred, meantime, tasted Broadway success without his sister and the offers began pouring in from Hollywood. As he would find with the death of his first wife, being split up from Adele was deeply traumatic, but he would conquer his feelings and get on with his career.

His new partner was Claire Luce, who would reveal that she had to cajole Fred into making their pairing more romantic.“Come on, Fred, I’m not your sister, you know!” she would yell at him. He made it work so well in The Gay Divorce that it became a huge hit and the success of the stage play was put down to Fred and Claire’s good work.

So much for missing his big sister!

In recent years, footage was uncovered of Fred performing in The Gay Divorce with Dorothy Stone, Claire’s successor, making it the earliest-known Fred footage.

We have all heard of the RKO screen test they did on Astaire around this time, the one where his report read “Can’t sing. Can’t act. Balding. Can dance a little.”

It was like saying Van Gogh was a dreadful home decorator, but if you placed some oil and canvas in front of him…

It was Fred himself who clarified that there really was such a report. However, cinema legend David O Selznick at least showed a modicum of intelligence, admitting, “I am uncertain about the man, but I feel, in spite of his enormous ears and bad chin line, that his charm is so tremendous that it comes through even on this wretched test.”

Incredible that they came so close to missing out, although someone else would surely have discovered Fred Astaire.

IN PART TWO: Fred’s career shot into overdrive as soon as Tinseltown realised what a talent he was – and Astaire would repay them with incredible success, the likes of which the business had never seen before.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe