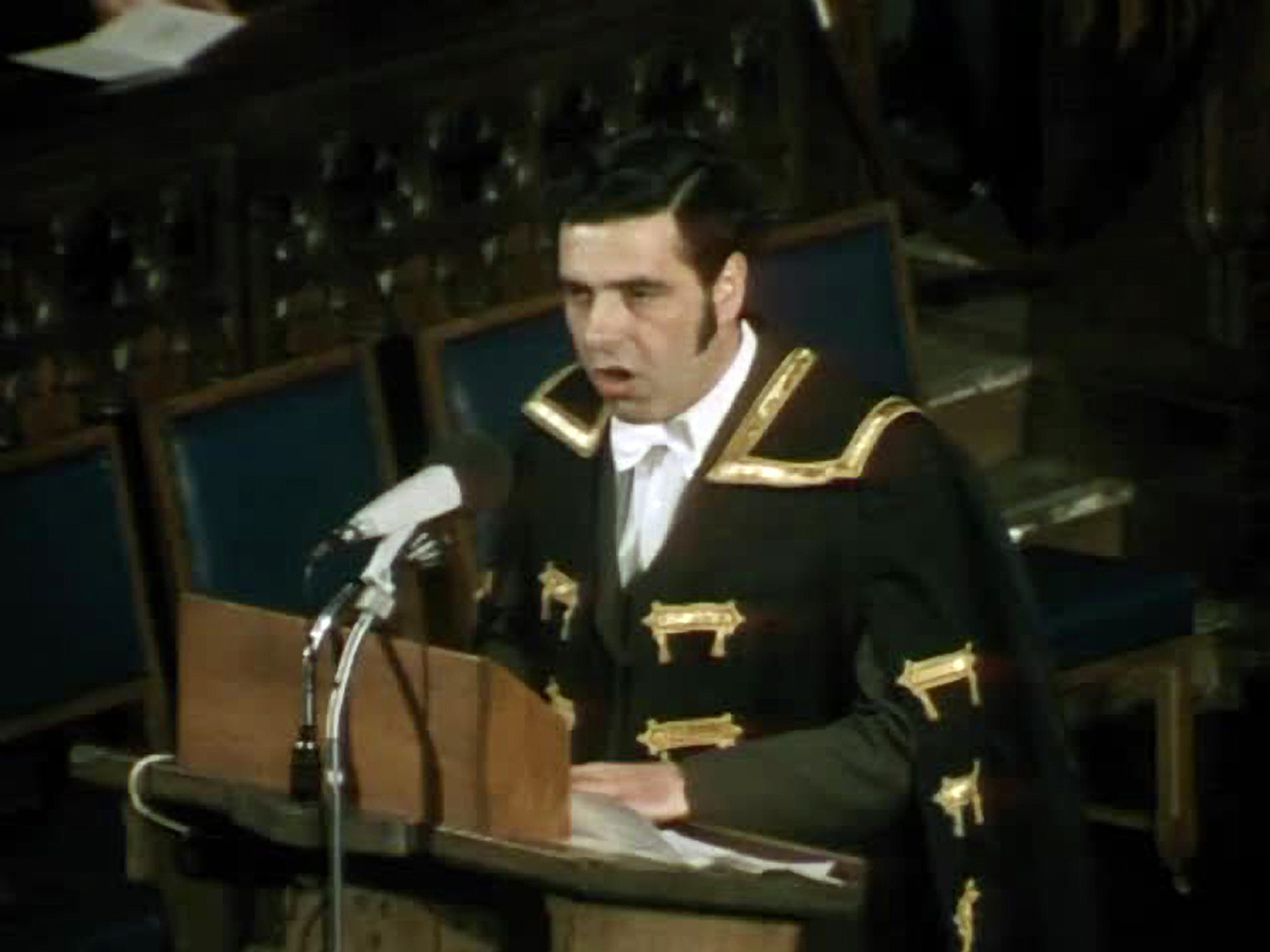

HIS speech wasn’t just covered by the Scottish media, but by the world at large.

While appreciative reporting might have been expected from some Scottish papers, the coverage in the New York Times could never have been anticipated.

It reprinted Jimmy’s speech in full, describing it as the most important speech since Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Praise, indeed, and from an unexpected but authoritative source.

Jimmy’s speech resonated so widely at the time because he had encapsulated the feelings of many towards monopoly capitalism.

Many saw their work and livelihood being bought and sold before their very eyes with little care for the consequences for them or effects on the wider community.

The ability of individuals to act or react was limited and a sense of powerlessness was growing. That frustration, as well as fear, was encapsulated in Jimmy’s short speech.

But what also mattered was that he said it needn’t be. He challenged and stood up to what had simply been taken for granted. He gave hope and belief that there was a better way. No wonder it resonated on the Hudson as well as on the Clyde. Given the success of the UCS work-in, there was also some ground for optimism.

It was to project Jimmy to a new level of popularity. He was no longer merely a very articulate shop steward, but a figure who could argue for a cause disdained by most.

Opportunities came to raise his own individual profile which he took to like a duck to water. Jimmy was a natural in front of the camera as well as on the political platform.

He was not just articulate and erudite but charming and thoughtful with it. The Communist Party remained keen to keep his profile high and pushed Jimmy relentlessly.

In October 1971, he appeared on the ITV programme Face the Press and performed remarkably well, sustaining an argument for the workers and socialism in a manner that was passionate but unthreatening. It most certainly wasn’t the monologue of an angry shop steward that many had expected.

People from all across the country wrote to the programme and to him personally. Those who were supportive of the socialist case were delighted to have such an appealing advocate and even those who disagreed, respected his reasoning and logic.

In 1973, he received an invitation to appear on the chat show hosted by Michael Parkinson. It was on at a prime-time slot on a Saturday night when television had far fewer channels.

He was beamed directly into people’s living rooms and the viewing figures were huge. Several weeks before, the comedian Kenneth Williams had been on the show and, having strident right-wing views, was scathing about socialism.

Condemnatory of trade unions, he had even accused them of ‘jeopardising their fellow man’. Michael Parkinson interjected at one stage to challenge Williams on some of his more outlandish claims, particularly when he contrasted his own actions as an aspiring actor with those working men.

It was thought appropriate to get Williams back on to the show along with an articulate trade unionist, no doubt to see what sparks might fly.

With Jimmy’s stock being high, what better contrast could there be than the plummy-voiced English actor and the Clydeside communist.

Many, and certainly the haughty actor, thought there would be no contest between the two. Parkinson later related how prior to the show, Williams had sought to belittle Jimmy. Williams quoted lines of classical poetry and arrogantly asked Jimmy if he knew who had written them.

He was gobsmacked when Jimmy accurately named the poet. Jimmy in turn went on to quote other lines and asked Williams if he knew who had written them. Williams had to confess that he didn’t and was astonished when Jimmy replied that he had.

The TV appearance was to be a surprise for the viewers who might have expected the shipyard worker to be pounded by the actor. As it was, Jimmy wiped the floor with Williams.

His breadth of knowledge along with his calm demeanour and general humility was a welcome contrast with the conceited manner of Williams.

‘A man of three parties but one clear vision’

Jimmy Reid was a member of three political parties but never elected to parliament.

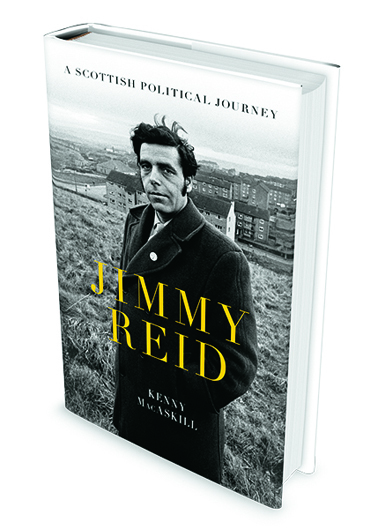

Kenny MacAskill, the former SNP justice secretary who has written a new biography of the Clydeside firebrand, believes that was the making of him.

Reid’s core beliefs remained constant throughout his early life as a Communist, his period as a Labour candidate in the 1970s, and when he finally joined the SNP in 2005, according to the former SNP Justice Secretary.

Mr MacAskill said: “Jimmy’s socialism was more rooted in morality than Marx. It was Christian socialism without the Christianity. He changed parties but not his fundamental values.

The biographer said that Jimmy, who died in 2010, was able to “rise above the battle because he was not narrow, partisan or self-seeking.”

And the former minister turned journalist and author said being in the Commons would not have suited the Govan-born man.

“In many ways he was fortunate he was never elected to parliament,” Mr MacAskill said.

“Had he been, he would probably have been unhappy, a backbencher who would have made some remarkable speeches but who would not have achieved what he did.”

Mr MacAskill decided to write the biography because he thought it was “rather shameful” there was no public chronicle of Jimmy’s life, which took in politics, trade unionism and journalism.

He said Reid’s passion and politics still resonate today: “He was a visionary in many ways.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe