Savage, destructive gales are becoming ever more frequent. The last few have been particularly terrifying, bringing the climate turmoil and true force of nature to our attention.

On the night of November 26, 2021, Storm Arwen hit many areas of Scotland, causing fearsome damage. In some places, the highest recorded gusts reached 177km/h (110mph).

At the beautiful Cluny House Gardens near Aberfeldy, famed for its rare Himalayan flora and spectacular trees, the storm’s severity was brutal.

As the mighty trees fell, they, in turn, caused further devastation to other precious plants at their feet, smashing rhododendrons and rare shrubs and shattering burgeoning young trees.

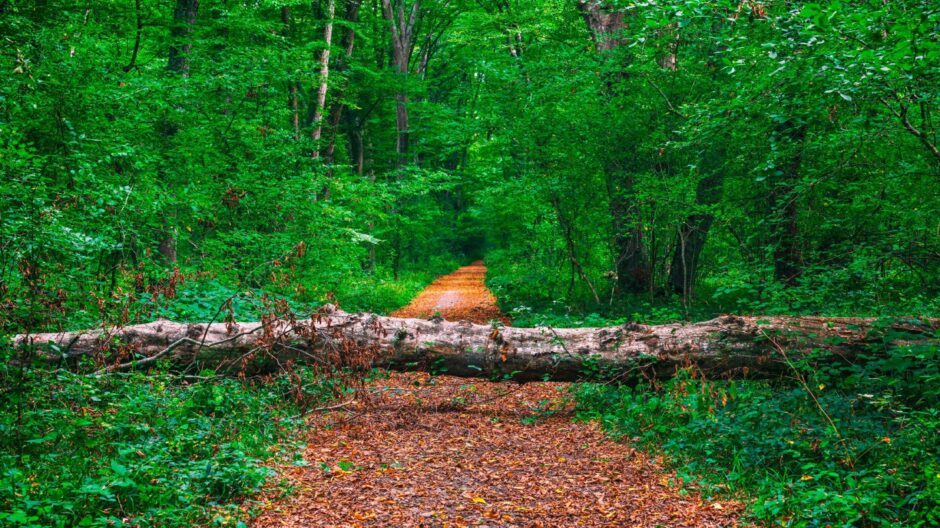

Garden owners Wendy and John Mattingley lay in bed while the sounds of the wind’s terrifying screaming and the ear-splitting bangs of falling trees filled the night. “In the house, the storm’s angry roar was louder than any we had ever witnessed; even interior doors and pictures trembled with the force,” Wendy says. “We had to sleep on the ground floor for fear the windows would implode. We heard explosive cracks and other petrifying loud creaking sounds as massive trees came down all around us. We were terrified of what would happen and what we would find as day broke.” By dawn, the calm was ominous. The Mattingleys found their garden devastated. Torn branches, ripped up vegetation and hundreds of giant redwood cones, as hard as golf balls, covered the 2.5 hectare (six-acre) site.

The garden was cut in half as eight 30-metre (98-foot) shelter belt conifers had come down, crushing other precious trees and numerous treasures beneath.

A 200-year-old walnut tree with a canopy spread of 15 metres (49 feet) lay ruined. It was a favourite of Cluny’s thriving red squirrel population, and now only its stump remained, pointing heavenwards – an irate warning finger stark against a bruised sky.

A pair of 200-year-old trees also demolished the Mattingleys’ full woodshed, and heavy limbs from numerous others landed on paths and flowerbeds, breaking everything. The woodland canopy creaked and groaned as suspended branches balanced like mammoths on a trapeze. Danger lurked everywhere. Huge trees had flattened perimeter deer fencing, too, while other sylvan giants had their roots so badly loosened that they will now have to be removed for safety reasons.

As well as the mayhem of finding an arboreal wasteland, the Mattingleys were concerned over the unseen wildlife dependent on Cluny’s rich ecosystem. Bats, birds, and one of the most significant red squirrel populations in Scotland were in jeopardy.

At Cluny, you are guaranteed to see these glorious arboreal acrobats. Visitors sit quietly, watching as they feed or bury stores in the leaf litter or dance nimbly like lithe gymnasts through the swaying canopy. Unfortunately, dreys and numerous bird and bat boxes were wrecked, and with the loss of the trees, natural shelter and nest sites have gone too.

Many enchanted visitors have described Cluny as heaven on earth. Bobby Masterton and his wife Betty bought it in the early 1950s. Then there were a few magnificent trees on-site, including conifers, beeches, and oaks, but most notably two vast redwoods, one with a girth of more than 11m (36ft). Although more than 150 years old, these natives of North America are still youngsters, for they can live for a thousand years. Happily, both behemoths remain intact. The Mastertons’ main interest was Himalayan and North American woodland plants that thrive in Cluny’s rich, damp loamy soil. Many of the seeds they lovingly nurtured are now large trees, but some are in the long list of casualties taken out prematurely. After Bobby died in 1986, the Mastertons’ youngest daughter Wendy and her husband John Mattingley took over.

“I took early retirement to work in the garden,” John says. “I loved to come at weekends and holidays to work alongside Wendy’s father, who taught us so much about Himalayan plants, Asiatic primulas, trees and shrubs. He loved creating something new, and we retain that ethos.

“We don’t use any chemicals or pesticides here and always garden with nature. It’s why Cluny has such a rich ecosystem. Dead wood is vital here too. When we had the chance to take it on, I knew that such opportunities only come along once in a lifetime. It was something outstandingly special, a way of life.”

“We are just amateurs,” adds Wendy with her trademark modesty as John bamboozles me with another blast of Latin names and tells me about some of the world’s rarest primula.

One of the many spectacular trees for which the garden is famous is the mature handkerchief tree, with its white leaf forms hanging like ghostly papers in late spring. Numerous Japanese maples, enkianthus and other berry-bearing trees and shrubs provide an impressive splash of colour in autumn.

Unfortunately, many of these will now have to be replaced. It will be vital to replant to give the garden structure and shade to bulbs and tuberous woodland perennials in the areas that have been laid bare.

Even at the age of five, Wendy, a naturalist of repute, knew more about plants than she ever did about dolls. She also has a particular passion and extraordinary knowledge of birds of prey. As a key member of the Tayside Raptor Study Group since its conception in 1991, she walks miles to keep long cold vigils in the hills monitoring merlins, hen harriers, eagles and ravens.

“Birds were always my first love,” she says, “But, now it’s fair to say it’s the garden too – and of course squirrels.”

Cluny is famed for John and Wendy’s sensitive approach, where a natural ethos lies in harmony with mosses, lichens, fungi and native flora. Moss fringes shaded paths beside eerie cobra and giant Himalayan lilies and the sculptural drama of ferns. Alien forms of electric yellow and green skunk cabbage grow in wet areas.

Clearings explode in spring with a profusion of colour, swathes of trilliums and vast spreading clumps of vibrant dog’s tooth violets mingle with stands of different species of Asian primulas, many exceptionally rare.

Only natural materials are used to make paths, bridges and bank reinforcements on the steep slopes, and new plants are carefully propagated by seed sourced from accredited collectors.

John and Wendy mentor numerous volunteers and young people who are interested in botany and garden maintenance, and some have gone on to become leading arborealists and horticulturalists.

One is Tom Christian, who then trained at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh and was based there working closely with the International Conifer Conservation Programme. He is one of the UK’s leading experts on conifers.

With help from their loyal friend, Fiona Broad, the Mattingleys have dedicated their lives to this unique arboretum to retain its extraordinary magical atmosphere.

The cost of restoring the garden will be exorbitant – deer fencing must be urgently replaced, and heavy lifting gear that can operate on steep slopes, as well as specialist tree surgery, is paramount.

Cluny is not only a priceless part of Scotland’s horticultural heritage, nationally renowned as one of the significant collections of Himalayan flora and rare species and an important visitor attraction in the heart of Big Tree Country, it is also far more.

It is a haven of solace, an ecological oasis for the endangered red squirrel, myriad birds, bats, fungi and invertebrates, a place of peace – of rich biodiversity in perfect balance in a troubled world.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM