Modern-day movies often try to be bigger and better than anything that’s gone before – in the 1920s, they really were.

It was the decade that saw a huge growth in the film industry and Hollywood starting to concentrate on full-length feature films for a fast-growing global audience.

Before that, it had been mostly shorts and two-reelers, films that weren’t considered long enough to be called features, running at under 40 minutes including often lengthy intros and end credits.

David Griffith from Kentucky may not be the best-known name in cinema today, but in the preceding decade his movies had shown what could be done.

Griffith made films that were huge, sprawling epics compared to so many shorts of the time, not least The Birth Of A Nation, his landmark blockbuster released in 1915.

At well over three hours, its length alone was a sensation – costing $100,000 to make, they reckon it has since made $100 million, and it was so long it needed a dozen reels and audiences got an intermission halfway through.

And it was silent!

It was also deeply controversial, telling the story of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination and the lives of two families during and after the American Civil War.

The film was also among the first to have a score for an orchestra, to have hundreds of extras and even a souvenir programme to read during it.

But it portrayed black people in a negative way and is said to have given the Ku Klux Klan a big boost.

It revolutionised the movies, though, and we would see all sorts of new ideas and audacious new methods used in the films of the 1920s.

Way Down East would be the biggest movie of 1920, and it too was directed and produced by Griffith.

Starring Lillian Gish, the silent romantic drama had the sort of ending that had those early audiences gripping their seats, already completely caught up in the story, which had lasted over two hours.

Compared to shorts by Charlie Chaplin and others, this was a brand-new type of thrill for cinemagoers.

There were gasps in cinemas across the land as Gish’s character was rescued from certain death on an icy river.

The story that had built up to this had been based around another controversial idea – Gish played a poor country girl tricked into a fake marriage and then left behind when she got pregnant.

When her baby dies, she wanders the land, seeking work, and rejecting other men’s advances along the way.

It would make a powerful and much talked about film now, a hundred years later, so the mind boggles at how it must have affected 1920 audiences.

The only thing not shocking is the amazing business it did that year.

Over The Hill To The Poorhouse, that year’s second-biggest movie, was also silent and also full of misery and despair.

It starred Mary Carr, alongside several of her own real-life children, and was the tale of a woman who never gets a shot at enjoying life because, well, she has so many children.

This one stretched to 11 reels, and if you think the USA went to the movies to cheer itself up between the world wars, it seems that was not the case.

Another of that pivotal year’s biggest films was shorter and needs little introduction.

Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde, starring John Barrymore, was of course a belter, originally penned by Robert Louis Stevenson.

Barrymore, a man who became such a big-screen icon and well-known face that they called him The Great Profile, hadn’t always wanted to act.

He’d fancied being an artist and in recent years had appeared in brainy highbrow pieces like Richard III and Hamlet, some saying he was America’s greatest living tragedian.

In this one, he was Henry Jekyll, London-based doctor of medicine who has a habit of turning into someone far nastier when he imbibes his mysterious potion.

There was quite a clamour to see it upon its release, with audiences seemingly turning from nice, calm people into vicious monsters too.

As one paper reported: “A door and two windows were broken by the crowds that tried to see it on its first showing in New York.”

Mass-audience movies, it seemed, and long ones at that, had truly arrived, and things would never be the same again after 1920.

The following year saw Charlie Chaplin getting into full-length work and his attempt became one of 1921’s biggest successes.

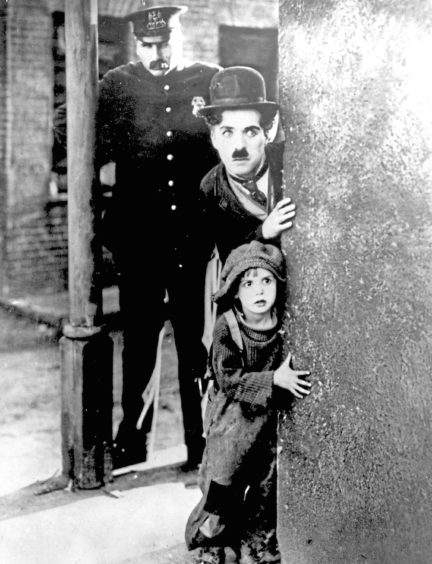

The Kid only lasted around the hour mark – there are 68-minute and 53-minute cuts – but it looks as wonderful today as it did 99 years back.

Jackie Coogan, who is also remembered for Uncle Fester, a very different role, several decades later, played the Kid to perfection.

They do say never to work with children or animals, but Charlie Chaplin worked extremely well with both.

Seen as one of the silent era’s best movies, and one of the best films of any era, Chaplin played The Tramp who finds the abandoned orphan and looks after him.

Personally, I went out and bought the DVD of this film a few months back and had forgotten how charming and hilarious and moving it was. What a genius Chaplin was.

The little boy throws stones at windows to smash them, then Tramp turns up to fix them and make a few dollars, with the cops always on their trail.

Meantime, though, the mother who abandoned Kid has become a famous and rich actress and she is going round, helping the poor. She even crosses paths with the Kid but fails to recognise him as her own.

In the end, she is shown the note she left when she abandoned him and, following a very surreal dream sequence featuring angels and devils, mother, son and Tramp are reunited.

The only movie to outperform The Kid that year was very different.

The Four Horsemen Of The Apocalypse stretched to well over two hours, an epic war flick based on the Spanish novel of the same name with Rudolph Valentino among its cast. It was, in fact, the film that made Valentino a star, and many also reckon it was the first anti-war film.

Yes, if 1920 audiences had wanted misery all the way, 1921 seems to have been the year when all extremes were welcome.

Italian-born Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Rafaello Guglielmi di Valentina d’Antonguella – you can see why they shorted it to Rudolph Valentino – proved very popular with men who loved good acting and women who loved good-looking men.

Valentino would be dead in a few years, aged just 31, a tragedy that caused mass hysteria in the United States, and it was because of the great job he did in movies like Four Horsemen.

One of the highest-grossing silent movies ever, it was also one of the first movies to make over a million dollars.

In 1926, when he died, Valentino’s health issues were so unusual that they were given their own name.

Valentino’s syndrome, they called it, as he had perforated ulcers that appeared to be mere appendicitis.

When he developed other symptoms and died, more than 100,000 mourners turned out in Manhattan for his funeral and there were reports of fans committing suicide.

Windows were smashed and a riot broke out, while an actress who claimed to be his fiancee collapsed at his coffin. Mussolini was said to be behind four actors in Fascist blackshirts turning up as a guard of honour.

As acting careers, and funerals, go, Rudolph Valentino’s was a bit special.

As was the cinema king of 1922, Robin Hood, written and produced by its star, Douglas Fairbanks, father of the Junior who would also become one of the most famous men in Hollywood.

Robin Hood was special, with a budget of a million dollars that was just about unheard of – it was also the first motion picture to get a Hollywood premiere, at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre.

After all the spending and big launch, thankfully it lived up to it, becoming the smash hit of that year.

Fairbanks would be best known for such swashbuckling roles, and this was one of his best, ranking with The Mark Of Zorro.

He would also go on to found United Artists along with Chaplin and others, and he would become known simply as The King Of Hollywood.

Alongside wife Mary Pickford, they really were America’s royalty.

Jackie Coogan was in the news again with that year’s other hit.

Oliver Twist proved immensely popular, with Jackie as Oliver and Lon Chaney as Fagin.

It’s little remembered now but, in those days long before Sir Sean Connery – not even born yet – or Deborah Kerr – born the previous year – a Scot played a major part in its success.

Frank Lloyd, born in Glasgow – Cambuslang, to be precise – directed this classic Oliver Twist.

All of which makes you wonder how they managed to lose it. It was only by chance that, in Yugoslavia in 1973, a print of the “lost” movie was found.

Thankfully, Jackie Coogan was still alive to help them restore some of the titles.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Moviestore / Shutterstock

© Moviestore / Shutterstock