The year 1923 was an interesting one for film.

Although the United States was still miles ahead in releasing multiple big-budget and epic-length movies, there were plenty of stars and great film-makers in Britain.

Some were learning the ropes but some had been working on silent shorts for a while.

One was Alfred Hitchcock – in his early 30s and still two years away from his full directorial debut.

The man cinema would soon know simply as Hitch did some uncredited directing in 1923’s Always Tell Your Wife, a short comedy starring Seymour Hicks and Gertrude McCoy.

Bonnie Prince Charlie saw Welsh actor Ivor Novello starring, and the story goes that he got so used to wearing the kilt while filming in the Scottish Highlands that he would often sport a kilt in years to come, much to his delight and the surprise of everyone else.

A silent historical drama about the Jacobite Rebellion, it is thought to be lost now, which is a shame as it sounds intriguing.

The Covered Wagon was a different story, made in the USA on a huge budget for its time, bringing in an absolute fortune and telling a wonderful tale.

This silent Western, from Paramount, was based on a novel about a pioneering group heading through the Old West from Kansas to Oregon. They came up against snow in the mountains, hunger for large parts of the journey, Indian attacks and desert heat.

Part of what made the movie so incredible was the real Native Americans hired to appear in it, along with genuine covered wagons that had been used by real-life pioneers.

The wagon owners and their families and animals were all paid to appear and go about their business as their forefathers would have done, lending the film an amazing realism.

No wonder, then, that it attracted a mass audience.

Like many of the films we’re talking about, it was released so long ago that it is now in the public domain, owned by no-one, and you can find it and many more on the internet and download them to keep.

It took a great man and a great woman to bring us 1923’s other box office sensation.

When we think of the classic epic The Ten Commandments today, producer-director Cecil B DeMille is the name that comes to mind, and he certainly knew how to make a film on a huge scale.

This one was the first part of his trilogy that would also include The King Of Kings and The Sign Of The Cross. No need to ask what they were all based on.

But it was the lesser-known Jeanie MacPherson who really put the whole thing together.

Boston-born Abbie Jean Macpherson had been an actress, but turned to writing and directing, working closely with DeMille and DW Griffith, the other giant of 1920s US cinema.

With her roots in Spain, Scotland and France, she had been sent to a fancy posh school in Paris before her parents ran into money troubles.

She came home, got a job and at the same time earned a degree and began dancing and doing stage work.

Jeanie was a decent singer too, but when films caught her eye her future was mapped out.

Having learned every aspect of acting and film-making, perhaps it was not such a surprise that she was able to write perfect screenplays – although for a woman to be doing it at that level in her day and age was incredible.

The Sea Hawk, 1924’s biggest hit, was pretty incredible too.

Directed by the great Frank Lloyd, it starred matinee idol Milton Sills, a man so good he would effortlessly make the tricky transition from silents to talkies but die of a heart attack just as his new talkie career was going into overdrive.

He played a wealthy baronet blamed for another man’s death and captured by Spaniards and made a galley slave.

Oliver Tressilian, his character, finally escapes to the Moors and reinvents himself as Sakr-el-Bahr, the enemy of Christendom. It would make a headline-hogging blockbuster today, and it did just that back in its own day.

Many silent stars, of course, would fail miserably to keep their careers going in the right direction once sound came in. Apart from anything else, some just had dreadful voices or accents a mass audience wouldn’t understand.

Few had learned to make talkies either, and while many an established star would disappear, Sills revelled in the new thing. How sad that he died while playing tennis with his wife, completely out of the blue, at just 48.

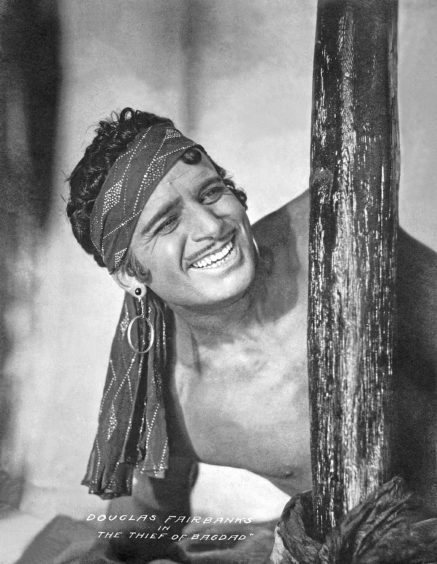

Douglas Fairbanks was the perfect example of a man who had been a massive superstar in the silent era and just didn’t cope with the talkies.

But he was the star of 1924’s other top flick, The Thief Of Bagdad.

It was another swashbuckling adventure, and cinema audiences back then clearly came to movies to be thrilled, scared and inspired.

Fairbanks, too, would not live a long life, dead at 56, but he would play a huge part in the history of cinema.

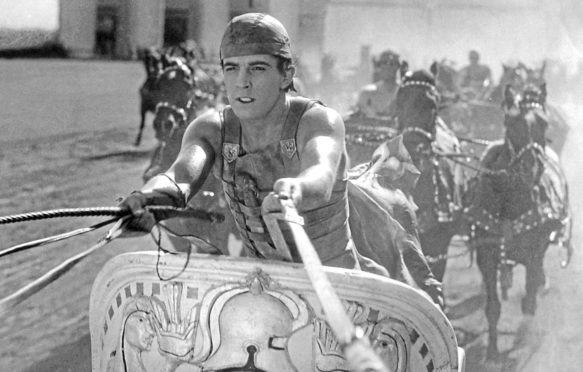

Ben-Hur, released 34 years before the version starring Charlton Heston, was the silent version and the biggest hit of 1925. This one starred Ramon Novarro, born in Mexico in 1899 and known in his heyday as a sex symbol.

Novarro had started with modest bit parts and boosted his income as a singing waiter, but friends reckoned he had the aura and looks to rival Rudolph Valentino.

We often hear how this and that actress’s revealing costumes caused outrage or sensation, but it was Novarro’s revealing outfits that got so many headlines for Ben-Hur.

When Valentino died the following year, Novarro became his natural successor for certain roles, and every actress wanted to be his leading lady.

Although he would do well in his first foray into talkies, work would later dry up, but Novarro had been shrewd enough to use his money sensibly and set himself up for life with one of Hollywood’s most admired homes.

The Big Parade, directed and produced by the magnificently-named King Vidor, gave Ben-Hur a run for its money in 1925.

A silent drama about a wealthy young man who joins the Rainbow Division of the US Army, it starred John Gilbert as James Apperson, the rich lad in question.

Apperson, who had been good at doing as little as possible back home, sees for himself the horrors of trench warfare but also finds true love with a French girl.

In the end, he lives up to his father’s hopes for him, becomes a man by what he goes through at the Front, and comes home to find everything in America has changed.

He has also had a leg amputated after being shot during an act of extreme heroism, and when he tells his family about the girl he loves in France he is told to go straight back there and find her again.

Lots of drama, a love affair, bravery and a nice morality tale – it had it all, and would surely have been top of the lot that year but for that pesky Ben-Hur.

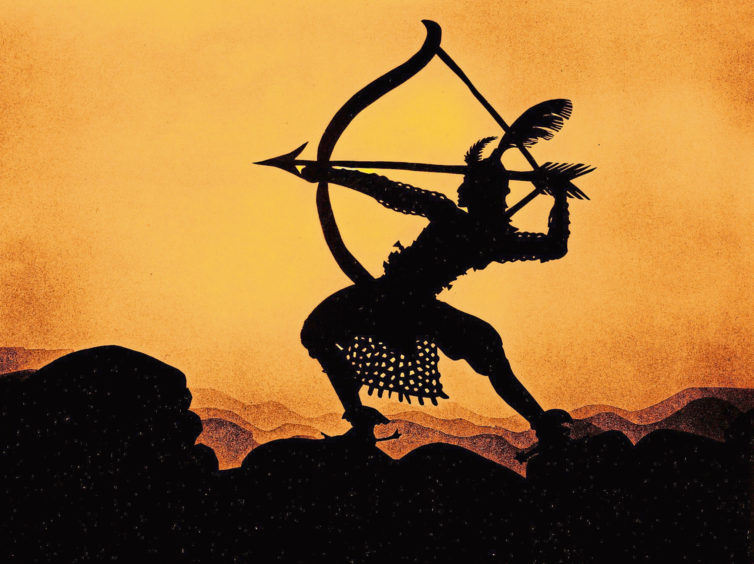

February of 1926 saw the making of a film that is little-known now but remains unique.

The Adventures Of Prince Achmed, an animated feature film released in the Weimar Republic, is now the oldest surviving animation of that length.

That year would also make cinema history as the one in which Rudolph Valentino’s death and funeral led to riots, even suicides, and it demonstrated just how important the world of films had become.

Which means Aloma Of The South Seas must have been pretty special.

The biggest film of the year was this silent comedy, with a bit of drama thrown in, and starring Gilda Gray as an erotic dancer.

It was one of the biggest movies of the whole decade.

The beautiful Gilda Gray had been born Marianna Michalska in Krakow, then part of Austria-Hungary but part of Poland today.

She made the so-called shimmy dance popular and, judging by the box office results, millions of people were only too keen to watch her dance, erotic or otherwise!

For Heaven’s Sake, produced by and starring the wonderful Harold Lloyd, ran Aloma close.

With his big, round spectacles and always on the hunt for money, fame and fortune, his character is ranked right up there with Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin.

This is the guy who was hanging from the clock hands high above the street in Safety Last, and a man who would lose a thumb and index finger after an accident with a prop bomb.

He really lived the job, doing his own stunts and churning out so many movies that, though Chaplin’s did better, it was Lloyd who made more money in total.

The remaining years of the decade would bring yet more cracking films.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © United Artists/Kobal/Shutterstock

© United Artists/Kobal/Shutterstock © Allstar/IMAGE ENTERTAINMENT

© Allstar/IMAGE ENTERTAINMENT