SIR DAVID ATTENBOROUGH was delighted with the recent naming of a 430 million-year-old fossil shrimp in his honour.

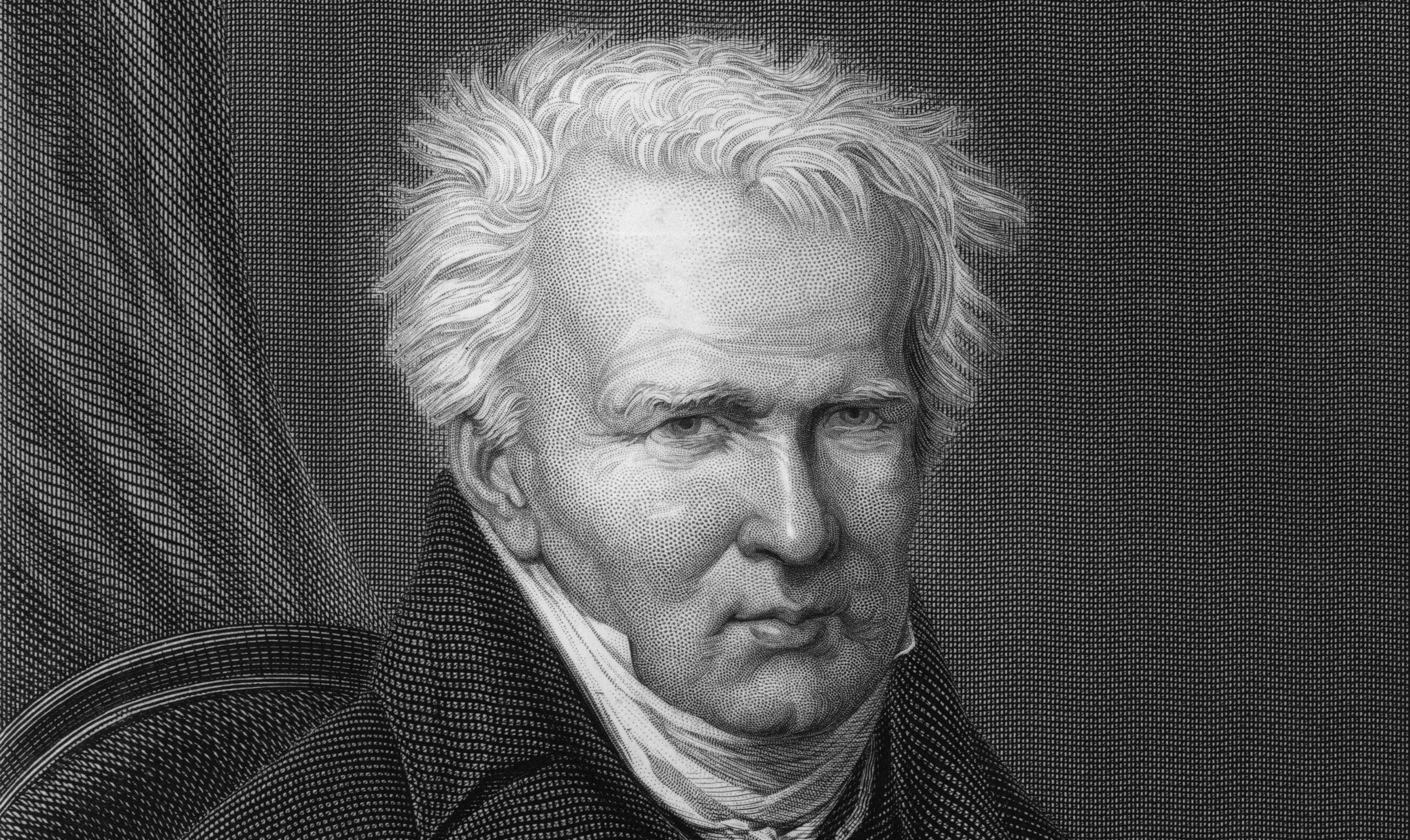

But the esteemed naturalist has some way to catch Alexander Von Humboldt, the man with more places and living things named after him than anyone else on Earth.

They include Humboldt penguins, monkeys, an orchid, a glacier, rivers, towns, mountains, an ocean current and even a sea, Mare Humboldtianum — on the moon!

And yet many people have never heard of Humboldt. What did he do to merit such honours?

Born in 1769, Humboldt was an intrepid explorer and naturalist from Prussia whose adventures took him to Latin America and into China.

In 1800, he and companion Bonpland paddled in a canoe for weeks, mapping crocodile-infested rivers in Venezuelan rainforest.

They were tortured by swarms of mosquitos that fogged the air and came face to face with deadly jaguars on land.

At Calabozo, in Venezuela, he heard from locals about electric eels that lurked in pools.

Very little was known about electricity so Humboldt was eager to see the creatures.

At six feet long and capable of a shock of 600 volts, capture and study posed problems.

Locals provided a grim solution — they drove a large group of wild horses into the pool.

The horses reared and thrashed in agony from violent electric shocks from the eels. Screeching in panic and pain, some crashed down and were trampled and drowned by others.

Gradually some charge from the eels was dissipated.

They still gave painful shocks as Humboldt and Bonpland discovered as they carried out tests such as touching the eels with their hands, then with metal implements and in circuit.

Wherever Humboldt went, he took frequent precise measurements of temperature, magnetic field and air pressure.

He even measured the blueness of the sky. It’s with this data that he later devised the isobars so familiar now in weather maps and also identified the magnetic equator.

He also took his treasured scientific instruments on the trek up Chimborazo in Ecuador, believed at the time to be the highest mountain in the world.

Suffering severely with altitude sickness, he and his party of four battled through snow and fog along precipitous ridges.

A ravine 1,000ft short of the 20,000ft summit thwarted the attempt to conquer it, but Humboldt had reached a greater altitude than anyone else in history.

Here, Humboldt had a flash of inspiration combining all the things he’d seen into a unified picture of nature.

He developed a theory of a web of life.

He knew that each strand was linked to and was co-dependent on so many others and that patterns were repeated across the globe. It is at the heart of modern ecology studies.

It’s to Humboldt that we owe our earliest theories on man-induced climate change.

At Lake Valencia, he noted how the felling of forest for timber caused soil erosion and flooding.

Trees provide cooling shade, restrict evaporation and maintain humidity.

He predicted the devastating effects their continued loss could have on climate.

In his published works, such as his masterpiece Cosmos, he argued forcibly for change in deforestation practices.

He also saw links between life forms on widely separated land masses, particularly South America and Africa.

He knew they had to have been joined at one time.

Humboldt had inched along on his stomach to peer into live volcanoes and attributed the movement of the continents to vast subterranean forces forcing them apart, long before anyone knew about plate tectonics.

Humboldt’s travels later brought him to London, and his insatiable curiosity took him and his scientific instruments to the bed of the River Thames.

He joined engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel in a two-ton diving bell as it was lowered to a depth of 36ft to inspect the troubled works of the first tunnel under the Thames. The bell’s windows were two feet thick. The painful increase in pressure on the descent caused blood vessels in Humboldt’s nose to burst.

Elsewhere, in his expedition to Russia in the 1820s, Humboldt predicted where the first diamonds in the country would be found.

He loved the summer steppes, ablaze with wild flowers, though again was plagued by mosquitoes. When they encountered an area devastated by anthrax, Humboldt ploughed onwards.

Eventually, he reached the border with China. He was delighted to spend a few hours with a Chinese commander and then a Mongolian leader in their respective yurts on opposite sides of a river.

The legacy of Humboldt, who died on May 6, 1859, aged 89, can be found in many modern environmental studies, so it’s little wonder Andrea Wulf, in the title of her excellent biography, attributes to him The Invention of Nature.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe