By the late Forties, Billie Holiday was riding the crest of a wave.

She had been earning what was a fortune in those days, was regularly voted one of the biggest female stars around, and had plenty reasons to be cheerful.

Sadly, she still turned to artificial stimulants to keep her happy, and in May of 1947 was arrested for narcotics possession in New York.

She would say that her time in court felt like it was the whole USA against her.

Feeling sick and unable to eat, she pleaded guilty and asked to be sent to hospital. After she was sent to a West Virginia prison, things changed.

She got out early for good behaviour but her management were unsure how she would be accepted at her first concerts. Billie herself was nervous about it.

They needn’t have been – Carnegie Hall sold out in record time, most unusual for someone without a current hit.

When a box of gardenias arrived from an admirer, she turned them into “My old trademark,” she said, “took them out and fastened them smack to the side of my head.”

Alas, there was also a hairpin, and though she sang on with blood streaming down her face, she collapsed after a third curtain call!

Despite all this, she was arrested again at the start of 1949, in her hotel in San Francisco.

She’d used pretty serious drugs since the start of the decade, and, after the 1947 incident, was barred from playing anywhere that sold booze.

If this side of her life disappointed some, it made little difference to her peers. Even Frank Sinatra said she was his biggest influence.

“Every major pop singer in the US during her generation has been touched in some way by her genius,” he said.

“It is Billie Holiday who was, and still remains, the greatest single musical influence on me. Lady Day is unquestionably the most important influence on American popular singing in the last 20 years.”

She had fans of every sort. Billie tells a great story in her book about a man showing up when her car was broken and literally getting his hands dirty fixing it for her, before driving her and friends to a posh hotel for a few drinks.

It was only when he was cleaned up a bit and she got a proper look at him that she realised it was Clark Gable.

As the Fifties approached, her style was definitely changing, with slower songs taking up more and more of her recording and live repertoire.

They suited her world-weary vocals, and seemed to bring out the best in her.

Many fans have said they appreciate how technically perfect and glorious Ella Fitzgerald and others sang, but only Billie Holiday had that intangible something that could break your heart.

As her drinking and drug abuse worsened, and one man after another treated her badly, the pain in her voice would only grow.

What wasn’t growing, however, was her fortune – the royalties coming in would shrink continuously in her later years, which is shocking when you think that all these years later people still make a fortune from each new generation of Holiday fans buying her albums.

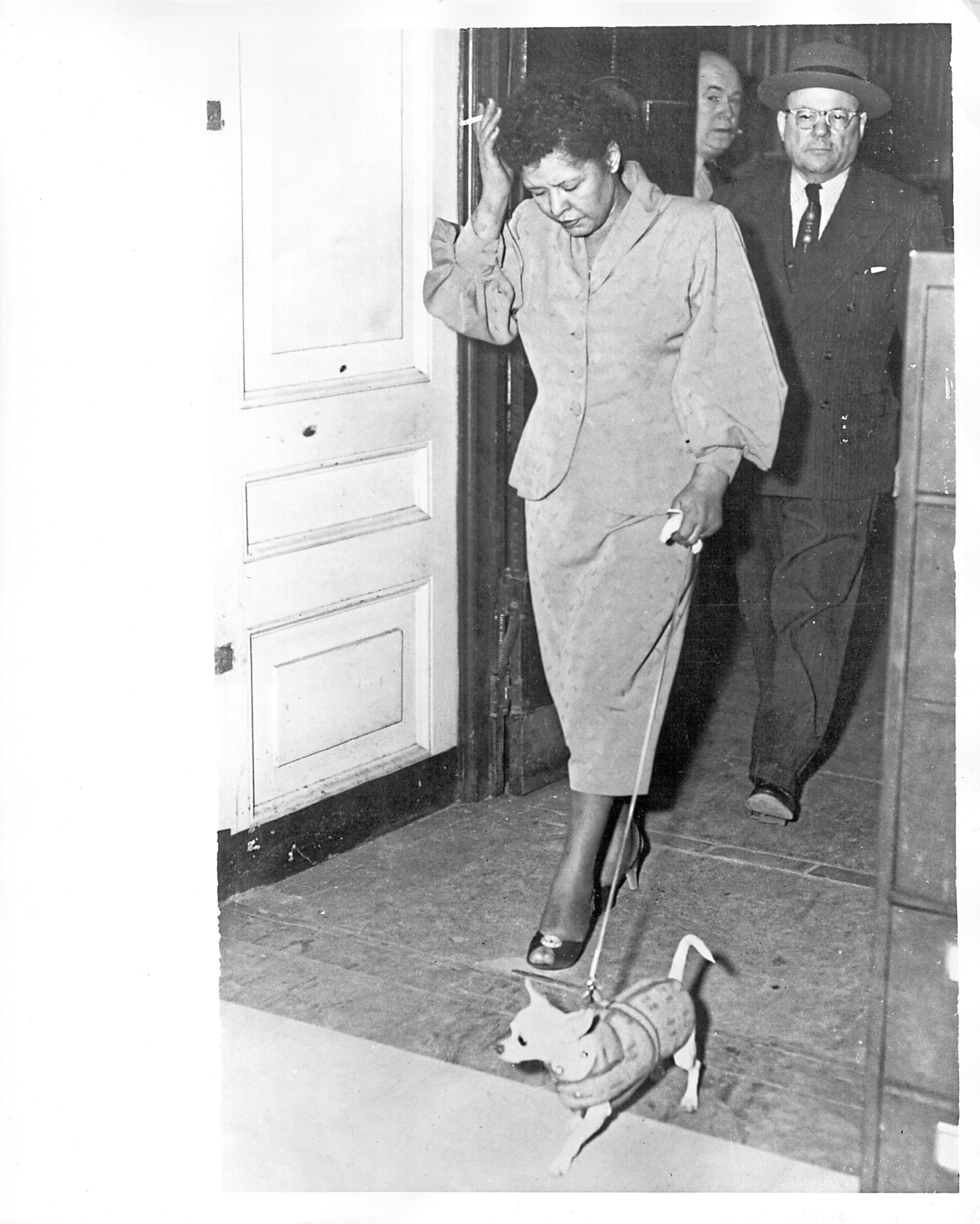

The one thing she could rely on wasn’t a record company boss or a lover – it was a dog.

Mister was his name and he was ever-faithful, by her side in the dressing-room before concerts, and waiting outside the prison gates when she got out.

She lovingly talked of how the dog leaped on her on one such occasion, with passers-by fearing he was attacking her.

“He began lapping me and loving me like crazy,” she said of her canine best pal.

Europe would be good to her, too, though, and her first foray into that continent went well.

The Jazz Club USA tour started in Stockholm, Sweden and continued through Germany, the Netherlands, France and Switzerland.

Billy

Billy

If Billie’s recordings from these later years showed a new, darker, sadder voice, they were and are classics in their own right.

They were done for the Verve label, beginning with 1956’s Lady Sings The Blues.

Released at the same time as the autobiography of the same name, it got rave, five-star reviews, and was the result of two recording sessions with two completely different bands.

Many reckon this was the last album on which her voice was the confident, bold version the world had got used to, and her later releases would show a more hesitant, unsure approach.

Body And Soul, from 1957, did indeed show a new voice, but still a great one. Clearly, however, fans could hear the results of her poor health and stressful life. Classics like They Can’t Take That Away From Me and Moonlight In Vermont actually seemed to benefit from the new singing style.

Moonlight In Vermont, the standard famed for its lines that don’t rhyme, was a good choice for Billie at this time, and she had lost none of her talent for selecting the best material and the best musicians.

The year 1957, though, demonstrated that she was still capable of bad decisions.

She married Louis McKay, who was not only a Mafia enforcer but seems to have been yet another man who treated her badly.

They were no longer together by the time of her death but that didn’t put him off the idea of opening a whole chain of Billie Holiday vocal studios, as others had done with dance schools.

Not that many people would believe you could simply bring kids in and teach them how to sing like Billie Holiday. That was something you were born with or not.

If Billie couldn’t seem to pick a good man, she was more often than not spot on with her music.

Her other album from that busy year, Songs For Distingue Lovers, was proof that she had not lost her taste and her wisdom when it came to what she sang and what recordings she put out.

Day In, Day Out kicks it off, and she also tackles One For My Baby (And One More For The Road) and Gershwin classics They Can’t Take That Away From Me and Let’s Call The Whole Thing Off.

Fans who have the 1997 version, where remastering it made it sound like Billie and band are right in the room with you, will know it’s a must-have for those just finding out about her.

The fact that the albums Stay With Me, All Or Nothing At All and Lady In Satin were all released in 1958 show just how much was expected of artists back then.

These days, if an established act puts out something new every few years, that is perfectly acceptable.

We can only be grateful that singers did that much recording, because Lady In Satin would prove to be the last Billie Holiday album released while she was still with us.

It was recorded for the Columbia label, whose producer Irving Townsend revealed that Billie came to them knowing exactly what she wanted.

“She said she wanted a pretty album, something delicate,” he explained. “She wasn’t interested in some wild swinging jam session, she wanted that cushion under her voice.”

If some of her vocal power was gone, she still had the phrasing that makes you listen to every word of any Billie Holiday recording.

Trumpet player Buck Clayton, who had worked with her much earlier, pointed out that he preferred this older, darker, smokier Holiday voice, even if it took a while to realise what a great record Lady In Satin is.

For bandleader Ray Ellis, the man Billie had requested to provide that “cushion”, with his massed violins, cellos and flutes: “The most emotional moment was her listening to the playback of I’m A Fool To Want You.

“There were tears in her eyes. I must admit I was unhappy with her performance, but I was just listening musically instead of emotionally. Weeks later, I realised how great her performance really was.”

The album turned out to be so good, in fact, that in 2000 it was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. What even those around her failed to get right away, Billie Holiday had understood the whole time.

Sadly, time was short now. In early ’59, she was diagnosed with cirrhosis. Billie quit booze but relapsed, and she had lost 20lb by May.

Nobody, it seems, could quite persuade her to go to hospital.

Finally rushed there on the last day of the month, she was arrested by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and handcuffed for drug possession, as she lay dying.

She passed away on July 17, of pulmonary edema and heart failure caused by cirrhosis of the liver. She was just 44 years old.

Billie had 70 cents in her bank and a tabloid payment of $750 on her person.

She was buried at Saint Raymond’s Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City.

Billie had virtually no musical training but had an incredible sixth sense about who should play on her records, who should produce and how she should bend and twist words and notes to get her unique sound.

And, as someone who had often said she wanted her voice to sound like another instrument in the mix, she had done that successfully.

She also gained plenty of knowledge of how mean and greedy the world could be, and the way she self-destructed suggests she eventually just couldn’t be bothered dealing with it any more.

At 44, she had left us more classic recordings than many who have released far more and lived much longer.

Not many singers can break hearts or inspire joy quite like the unique Lady Day.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

© Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images