This time of year is when the world is reminded of one of its most distinctive voices ever.

When White Christmas floats out of radios, TVs and streaming devices everywhere, the unmistakable voice of Bing Crosby wins a whole new generation of fans.

Not that the great Bing only had one hit, or was just a singer.

The man born Harry Lillis Crosby, Jr on May 3 1903, in Tacoma, Washington State, would become one of the best-known showbiz superstars of all time.

He’d live to the age of 74, have two wives, seven kids, and a triple career as a comic, actor and singer.

Not to mention that he was a very handy golfer and racehorse breeder, helped develop video recorders and studios’ recording process and was the first man to pre-record radio shows and save them on magnetic tape.

Crosby was a man of his times and a man ahead of his time, and if the gentle charmer of the big screen was what appealed to most of us, there was also a genius in many fields behind the smile, too.

Born into a house that his father had built himself, perhaps we should have known that Bing would grow into a very capable jack of all trades.

The fourth of seven children, he also had to be special to stand out, but Bing Crosby would find standing out no problem at all.

Bing would once claim that he got the nickname because as a toddler he would shoot passers-by with two wooden revolvers, yelling “Bing!” as he did.

It was only later that a neighbour corrected this version, Valentine Hobart insisting that he got the name from her nickname for him, Bingo From Bingville, after a comic in a local paper, The Bingville Bugle.

Harry, she said, looked just like him, and the nickname was soon shortened to just Bing.

Crosby was also still young when he witnessed the act who would inspire him and propel him towards a life in showbusiness.

Aged 14, he had a summer job at a local auditorium that hosted some of 1917’s biggest stars, and the teenage Bing was overwhelmed by Al Jolson, who did parodies of Hawaiian songs to everyone’s amusement and effortlessly made up his show as he went along.

Bing would call the performance “electric” and he certainly tried to take that off-the-cuff approach into his own work in the years ahead.

For one thing, helped by developments in technology, he would develop the crooning style that everyone would soon recognise, getting up real close to the microphone and half-talking, half-singing.

As his record sales would prove, it was an approach the world would love, and still does.

Just ask Bryan Ferry!

He graduated from school in 1920 and, though he attended university for a few years, Bing didn’t get a degree, although he was impressive on the baseball team.

By 1937, he was so popular that they gave him an honorary doctorate, anyway, and if you go to Gonzaga University now, you’ll find plenty photographic and other evidence of his life, career and schooldays.

He was still just into his 20s when he and friends headed to California to try and make it big.

Although he made good contacts, his first recording was done at the wrong speed, meaning his voice was too high-pitched when played at 78rpm.

Perhaps that was another reason for him getting to know how studios worked so intimately – to avoid any further mishaps!

New York beckoned next, and Bing got to perform alongside some huge names, like Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Bix Beiderbecke and Hoagy Carmichael.

Being in the same halls and studios as those men rubbed off, and he was soon doing well as a solo star himself.

Ol’ Man River in 1928 gave him his first No 1 hit.

At the time, he was part of a band called the Rhythm Boys, but his solo spots stole the show.

Inevitably, the other guys soon became unnecessary, and he got a solo recording deal, leading the group to part ways.

One person he was keen to get together with, though, was Dixie Lee, who became his first wife in September 1930.

A nightclub singer and actress, Dixie would die of ovarian cancer in 1952.

The couple had four sons together, Gary, Lindsay and twins Dennis and Phillip.

Gary, too, lost his life to cancer aged just 62, while Phillip died of a heart attack in 2004.

Tragically, Lindsay and Dennis both shot themselves dead, aged 51 and 56.

His marriage to Dixie, however, was a happy one, and Bing seemed to have thrown himself into his work even more thoroughly than usual.

In early September of 1931, Bing made his nationwide radio solo debut.

If the thought of that made any singer nervous, Crosby coasted it ending the year by signing with Brunswick and CBS Radio.

Songs such as Out Of Nowhere and At Your Command were among the year’s best sellers, and of the Top 50 songs of 1931, Bing featured on 10, solo or part of a band.

He spent part of the following year doing his first full-length film, The Big Broadcast, one of almost 80 movies he’d make.

It did so well that he got his first contract with Paramount. Bing’s weekly radio shows and earlier commercials also happened at this busy time, making it clear how quickly he became a household name.

In the Depression, with record sales dipping as nobody had money for such luxuries, Bing Crosby’s records were the exception to the rule, selling like hotcakes despite that.

Steve Hoffman, an audio engineer, would point out: “Bing actually saved the record business in 1934, when he agreed to support Decca founder Jack Kapp’s crazy idea of lowering the price of singles from a dollar to 35 cents!”

If he had taken inspiration for ad-lib from Al Jolson, he certainly didn’t follow Jolson’s singing style.

Jolson was known for belting because he had to holler loud enough without a microphone for those in the back rows to hear.

It wasn’t to Bing’s taste at all.

He trusted in getting right up at the microphone, so that you could hear every breath between the lyrics and his musical ideas saw him click with other artists.

Louis Armstrong, one man Bing admired deeply, became his pal almost as soon as they first met.

Their friendship had Bing fighting to have Armstrong in a movie with him, against studio bosses’ wishes, paving the way for other African Americans to also get film parts.

Bing also made sure Louis would receive the same prominent billing as the film’s white stars and Armstrong would often speak of Bing’s progressive attitude towards race.

Crosby’s earliest movies did well, but very few had the critics lavishing him with praise.

The 1933 film Going Hollywood was a good example of this.

The movie did well, but his performance was damned by faint praise.

Words like “amusing”, “modest” and “pleasant” were used, which must have been frustrating for the cast and crew when so much effort was put into these flicks.

So Sing You Sinners, from 1938, would have been a welcome change of pace, as critics seemed to recognise that he was coming out of his comfort zone and trying new roles.

“A new and interesting Bing Crosby emerges,” wrote one, “a likeable ne’er-do-well who believes that the secret of success lies in taking gambles.”

The story of three singing brothers who head for California seeking fame and fortune, must have struck a chord with his own story.

The film also introduced Small Fry and I’ve Got A Pocketful Of Dreams, both of which would become Crosby hits, the former done as a duet with the great Johnny Mercer.

As if he wasn’t a big enough star by 1940, Bing chose that year to launch himself on a series of movies that would send him into the stratosphere.

The Road To series, seven films in all, would play a huge part in Crosby’s success, making him the biggest star in the world, both through and after the Second World War.

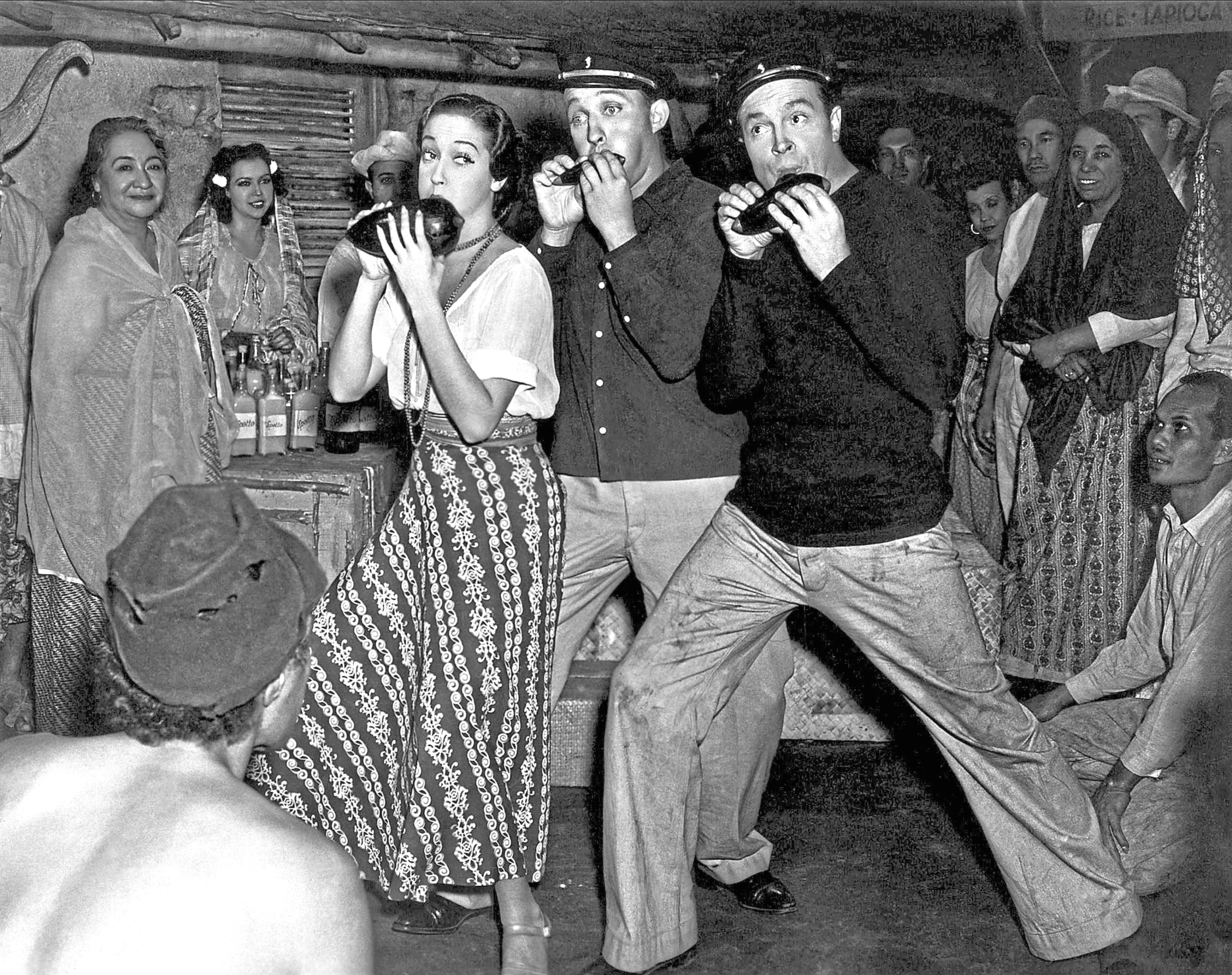

He starred in the comedies alongside Bob Hope and Dorothy Lamour, which were so popular that even the threesome were taken aback at how well the first one did.

Road To Singapore saw Bing and Bob as two playboys who head to Singapore in an attempt to recover from failed romances.

They meet a beautiful woman, Lamour, who they rescue from her dance partner which is where the music and comedy begins.

Fans will know that the Road To movies featured a few gags that would be repeated in each film.

One was the pat-a-cake, which would see two actors distracting someone by playing patty-cake before turning the game into a fist-fight which would let them escape.

Other jokes that would reappear throughout the series included references to Bing’s “spare tyre” and the two leading men usually performing as con men.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © LMPC via Getty Images

© LMPC via Getty Images

© Allstar / MGM

© Allstar / MGM