IF any aspiring pop stars feel like giving up after their first singles sell poorly, they could do worse than get a bit of David Bowie’s attitude.

The late rock star, who passed away in January 2016, went from being a fan of The Kinks, Beatles and Stones to rubbing shoulders with them and even outselling them.

And he did it all despite suffering one flop after another in his early years – Bowie just kept on going and worked obsessively on his songwriting talent, musicianship and concert skills.

Mind you, he didn’t always do it as David Bowie.

He was born David Robert Jones in Brixton on January 8, same birthday as Elvis, 1947.

His first single, Liza Jane, was released under the name Davie Jones and The King Bees.

It did precisely nothing in any chart, and nor did the next one, with a new band The Manish Boys.

I Pity The Fool was slightly better but nobody noticed it either.

Next came You’ve Got A Habit Of Leaving, as Davy Jones and The Lower Third, followed by Can’t Help Thinking About Me. This last one, also with The Lower Third, was the first single to feature his new name, David Bowie.

And it also did zilch in the charts. Was the Brixton boy for giving up and getting a regular nine-to-five job? No, thanks.

Do Anything You Say, I Dig Everything and Rubber Band saw Bowie try new styles and sounds constantly, and he’d become a master at reinventing himself.

None of it worked, but then came a song that he would spend many years trying to forget about, even if the real Bowie fanatics loved it.

Complete with speeded-up gnome voices, dreadful gnome puns and a bizarre little tale done in his best Anthony Newley Cockney voice, The Laughing Gnome finally got him a tiny bit of attention.

Alas, it was soon back to failure with yet another single, Love You Till Tuesday. Clearly, something big needed to happen to get him some serious attention.

The Moon Landings were just that thing, and although the original idea had been sparked by the Space Odyssey movie in 1968, Bowie’s tale of Ground Control failing to get Major Tom back from his mission was the big moment he’d dreamed of.

Space Oddity would become a classic, but Tony Visconti – the man who would work closely with Bowie for much of his career and produce some of his greatest records – thought it was a bit cheesy and didn’t fancy working on it. The American producer, also a great bass player who would marry Mary Hopkin, did the rest of Bowie’s Space Oddity album, but left the single to others.

He has since, on more than one occasion, held his hands up and admitted that yes, Space Oddity was and is rather good.

You wonder how Tony felt when Chris Hadfield did a version of it from the International Space Station. Last time I looked, the video of it on YouTube had been enjoyed by 44 million people.

If it seemed after that astonishing summer of ’69 that Bowie had arrived and could do no wrong, that was far from the case.

The Space Oddity album sold OK but nothing special, and Bowie went back to the drawing board.

This time, instead of the folksy, whimsical peace-loving hippy stuff on Space Oddity, he grew out his curly hair and had it straight and down to his backside and tried a heavier, guitar-drenched album, The Man Who Sold The World.

If he was trying to sound like the big macho rockers of the day, he certainly didn’t go for the jeans and leather look. Bowie being Bowie, he wore a “man’s dress” for the album sleeve.

Looking for all the world like a young Lauren Bacall, he lounged on a couch, with playing cards strewn around him on the floor.

You can only imagine how the record company must have despaired, but he did at least have a decent contract and they clearly believed that if he could write a Space Oddity, there would be more good material in this guy.

The Man Who Sold The World itself was a nice song, later done in a funky version by Lulu, Bowie accompanying her on voice and saxophone.

If other tracks on the album were a bit dark, dealing with such things as megalomaniacs and mental illness, well, these were the sorts of topic that Bowie would tackle again and again.

He would often talk about tyrants, Hitler or Stalin types, a topic that fascinated him, and he also spoke of the mental troubles that some members of his family suffered and that he feared he might have himself one day.

He had an older half-brother, Terry Burns, who would introduce the impressionable David to everything from Buddhism to jazz, the Beat Poets to the best London music clubs.

Bowie witnessed him having psychotic episodes and, after a life in and out of mental institutions, Terry walked in front of a train in the 1980s and killed himself.

If The Man Who Sold The World was, therefore, mostly dark and scary, it also showed this latest Bowie was more interested in writing songs that meant something to him, rather than just chasing hits, fame and fortune.

To his record company’s relief, the run of albums and singles that many consider his greatest achievements were just around the next corner. They would make Bowie bigger than the recently-dissolved Beatles or anyone else for a few years and see him with multiple singles in the charts at the same time.

Even The Laughing Gnome would become a hit all over again, and in the album charts he just ran riot, with six at the high end of the UK charts simultaneously.First, though, Bowie did what Paul McCartney and every other top rock star had done before him.

He locked himself away in a room full of instruments and went through blood, sweat and tears to master the songwriting craft and play piano almost as well as he could play saxophone and 12-string guitar.

The end result was a flood of songs, so many that he took his band into the studio and recorded Hunky Dory, one of his best-ever collections, and The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, many fans’ favourite.

Hunky Dory was produced by Ken Scott, who had worked as a young engineer on The Beatles’ White Album.

Scott had begun at just 16, working in the Abbey Road tape library – if you see pics, he looked even younger – and he happily admits that it never occurred to him with Bowie that Hunky Dory and Ziggy would still obsess millions of fans to this day.

Although it was the brilliant Rick Wakeman who played the trickier piano parts on Hunky Dory, it was clear that Bowie’s material was better now, and being able to write on piano rather than just a few guitar chords had helped.

You write things on piano that you could never dream up on guitar, simply because of the way the keys are laid out compared to six or 12 strings.

Bowie’s dedication to becoming a very useful keyboard player would revolutionise the way he wrote and the quality of his songs.

Life On Mars and Changes would become hugely important songs in the Bowie catalogue, while Oh! You Pretty Things was released as a single by Peter Noone of Herman’s Hermits fame, Bowie accompanying him on piano.

It reached No 12 in the UK charts, so now Bowie was not just having his own hit singles, but writing them for others, too.

In years to come, he would write the classic All The Young Dudes and simply give it away to Mott The Hoople, who would revive their career by having a massive hit with it. For a man who had struggled to get his first hit, he could be a very generous man with his material.

Even a nice light song suitable for Peter Noone, however, had Bowie hallmarks that would become familiar.

Black magician and occultist Aleister Crowley was referred to in the lyrics, as was Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher whose work became associated with the Nazis and the idea of a super race.

David Bowie, even at the age of 24, didn’t do light pop songs without some kind of dark edge.

The rest of Hunky Dory was incredible in its variety, and he did a few songs that were a nod to his heroes.

Song For Bob Dylan spoke of how he’d love to meet the American legend, while Andy Warhol was a whimsical little song about the Pop Art guru.

There then came another overnight change, the sort that Bowie fans would happily get used to over the years.

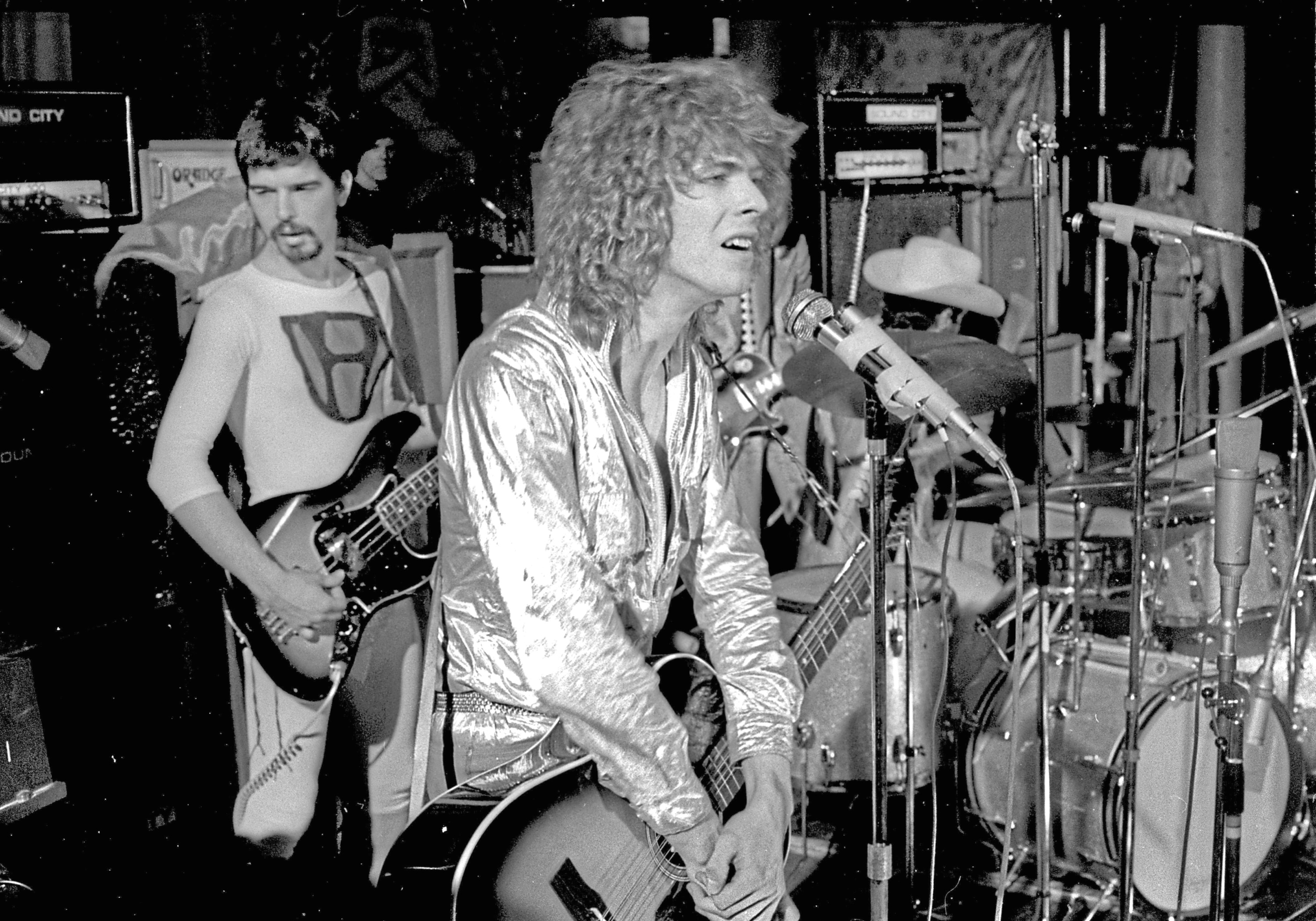

Between the Hunky Dory sessions and the Ziggy ones, he lost the long blond hair and the man dresses and Oxford bags, got his hair cut in a punky, short style and dyed carrot-orange and took to wearing a jumpsuit or outrageous outfits of every description.

Then he pulled on his platform boots, applied his mascara, cajoled his reluctant band to dress up similarly, and launched Ziggy Stardust.

As you’ll see in next week’s second part of our David Bowie series, Ziggy would take over the world.

Alas, he would also take over Bowie, who got so lost in the character that he began to forget he was actually David Bowie, or Davie Jones.

It would take him a while to sort himself out, but while he did so he became a megastar to rival any of his teenage heroes.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Ray Stevenson/Shutterstock

© Ray Stevenson/Shutterstock