Not many stars can straddle country, gospel and rock ’n’ roll – Johnny Cash did it so well that he was recognised in all three Halls of Fame.

The man with the all-black wardrobe and deep baritone voice was a huge star while still in his 20s, and in his twilight years was putting out some of his greatest recordings.

He could sell out tours across the globe, had the most distinctive voice in music and seemed to get cooler the older he got, but he still told each concert audience, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash” as if they might not be sure who he was.

Maybe it was that mix of modesty and brilliance that made him a legend to fans of every description and age range – you really did see five-year-olds and 100-year-olds at Johnny Cash gigs.

With over 90 million records sold, he was one of the best-selling artists of all time, and also a very decent actor and writer.

Born in Kingsland, Arkansas, on February 26 1932, JR Cash had English and Scottish roots.

When he met Major Michael Crichton-Stuart, laird of Falkland, Johnny was able to trace his surname to 11th-Century Fife, a long way from the prairies and American landscapes he loved singing about.

His parents were Ray Cash and Carrie Cloveree, and he was the fourth of their seven children. It was only when he tried to enlist in the US Air Force he was told he couldn’t simply use JR Cash as his name, so he changed it to John R Cash.

And in 1955, signing for Sun Records, he began to use the name Johnny Cash all the time.

That was all in the future, though, and his earliest memories would be of Dyess, Arkansas, a place where poor families were given a chance to work the land as part of a colony and, if they did it well, they could end up owning it.

This was why he found himself working his backside off in cotton fields at the age of five, but he sang his heart out to make the time pass, a sign of what would make life much more bearable in years to come.

Johnny would recall experiences like these grim early days when he wrote songs, and Cash was usually on the side of the poor, downtrodden working man and his penniless family.

He would also never forget his beloved big brother Jack. In 1944, he got dragged into a table saw and suffered terribly for a week before dying, aged just 15.

Johnny would often speak about the guilt he and his parents had felt, and of how Jack had visions of Heaven and angels on his deathbed.

A man of deep faith, Cash would speak the rest of his life about how he looked forward to being with Jack again when he, too, went to Heaven. Church played a big part in his childhood and youth, and he loved gospel music.

His mother taught him some chords on guitar and, though his voice was amazingly high as a kid, he would later develop the much deeper sound the world came to love.

Cash apparently also loved Irish traditional tunes, which he would hear on US radio stations.

He was only months into his 18th year when he enlisted with the US Air Force, where he worked as a Morse code operator, intercepting Soviet transmissions.

If this was quite a job for a young man, he also managed to find time for The Landsberg Barbarians, his oddly-named first band. It was also at this time that Johnny got the distinctive scar on his jaw, though it was nothing to do with fighting Soviets – he had surgery to remove a cyst.

In the summer of ’51, aged just 19, he fell for 17-year-old Vivian Liberto, not literally, at a skating rink and he and the Italian-American became an item.

They married in 1954 and had four daughters, including Rosanne, who would become rather famous herself in the music world.

With 11 No 1 country singles in the US, she almost rivalled her dad at times.

Sadly, the marriage would last just a dozen years, with his first wife blaming his alcohol and drug abuse for driving them apart.

The year 1954 was a big one for Johnny for other reasons, too. He and Vivian had moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he became an appliance salesman while learning to be a radio announcer.

In the evenings, he would play with other musicians and eventually he dropped in on the famous Sun Records studio and suggested he might be worth a recording deal.

Sam Phillips, who would also play a pivotal role in the careers of Elvis, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and others, is said to have poured scorn on Cash’s gospel material.

“Go home and sin, then come back with a song I can sell!” is what some reckon Phillips told him, although Johnny later denied this had been said.

Either way, he did indeed come back with songs that Sam liked a lot more – Hey Porter and other early recordings at Sun met with success, and Cash was on his way.

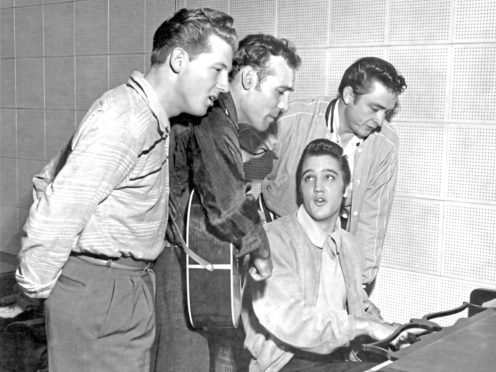

Some amazing old tapes were recorded back then but only released in 1990 – The Million Dollar Quartet was a Sun recording featuring Cash, Elvis, Carl Perkins and Jerry Lee Lewis.

The interesting aspect, apart from the fact we had four of the greatest rockers of all time on the one session, was how high Cash sang – placed furthest from the microphone, he sang that way to blend in with Presley’s voice!

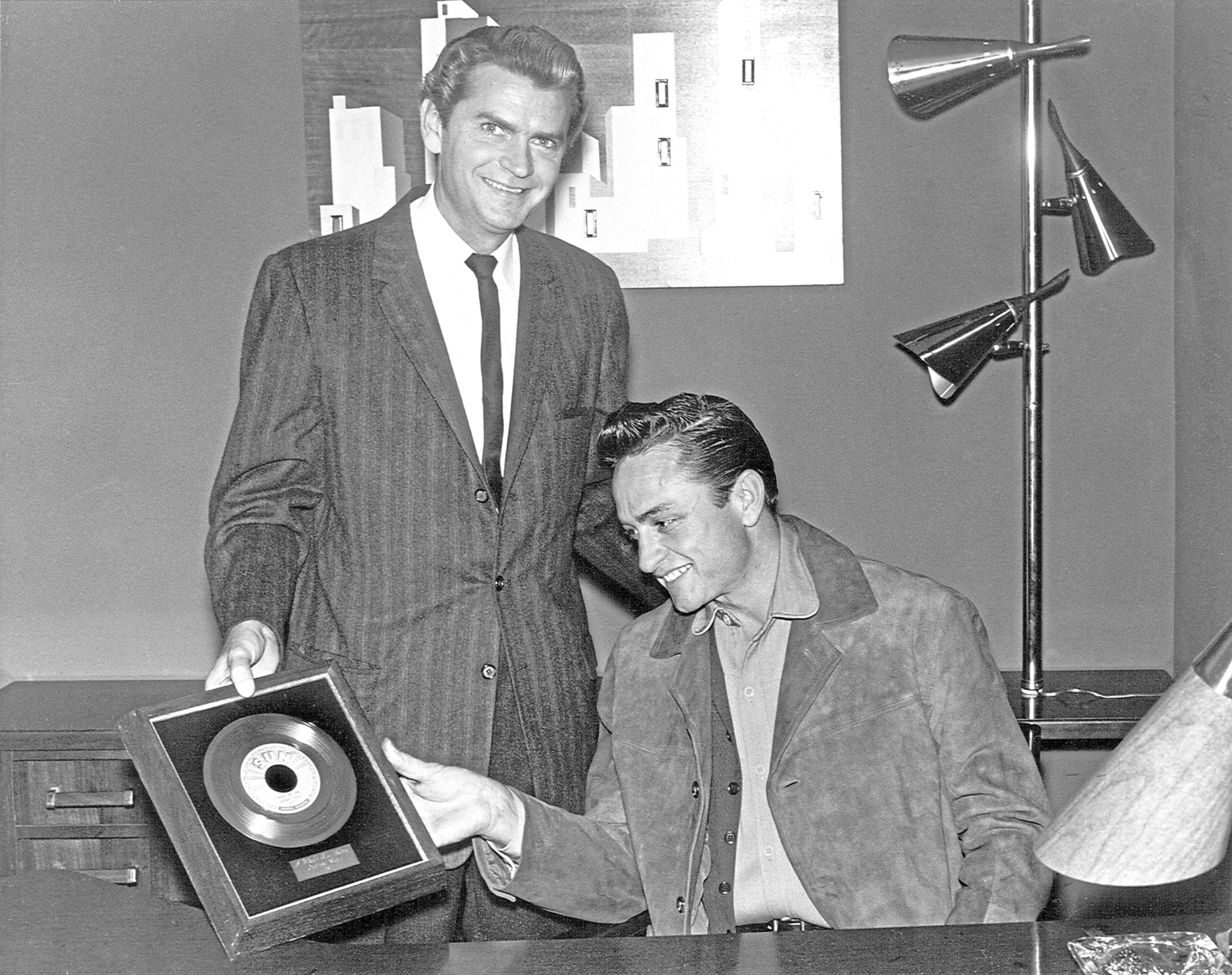

You can’t really write about the career of Johnny Cash without mentioning a man who was often his polar opposite, and yet who helped Cash’s career no end. This was his manager, Saul Holiff, and a magnificent film about the pair was released in 2012, made by Holiff’s son, Jonathan.

He was inspired to direct and produce it after finding audio diaries and documents, as well as a framed gold record for A Boy Name Sue, in his late father’s storage locker.

It seems that, with Cash being a born-again Christian and Holiff an atheist, they didn’t always see eye to eye, and it was a fragile relationship at times, if also lucrative.

The movie is full of amazing footage of the pair back in their heyday, and well worth a look if you’re a Cash devotee. Not that Johnny ever needed other people to make great music, he was always adaptable, onstage and in the studio.

For instance, when he was without the luxury of a drummer, Cash simply folded a dollar bill under his strings and made sure the microphone picked up its percussive qualities. This became another part of the signature Johnny Cash sound.

Johnny’s signature song, Folsom Prison Blues, was also written and recorded back in the Sun days, making the top five in the country charts.

It is famous, or infamous, for the line “I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die” and while it’s true that Cash did spend the occasional night behind bars, those short stays were for lesser demeanours.

Describing writing it, he would later explain, “I sat with my pen in my hand, trying to think up the worst reason a person could have for killing another person, and that’s what came to mind.”

Still, it would sound strange, to hear him sing such a line to real convicts when he came to do his legendary concerts in US prisons.

For now, though, his career was just getting up a head of steam, and when I Walk The Line made top spot in the country charts and also troubled the pop charts’ Top 20, Cash was thrilled.

He would also become the first Sun artist to put out a whole long-playing album, but behind the scenes Johnny was wondering if he couldn’t get more money and more success elsewhere.

Elvis had already left Sun and Sam Phillips was focused on making Jerry Lee Lewis as big as he could, so perhaps this was also in Johnny’s mind.

Whatever the reasons, he would soon leave Sun behind and head to Columbia Records, who had given him a fantastic offer.

The switch got off to a great start with Don’t Take Your Guns To Town being a massive hit, one of the biggest he ever had.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

© Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images © Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

© Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images © Colin Escott/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

© Colin Escott/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images