Johnny Cash had shaken off his drug and drink issues and kept well away from jails by the end of the 60s.

Ironic, then, that two of his greatest works from the era happened behind bars.

The live albums At Folsom Prison and At San Quentin, from 1968 and 1969 respectively, rank among the greatest concert recordings of all time.

He’d fancied doing it for a while, but it was only the arrival at Columbia Records of Bob Johnston that allowed him to proceed.

Other executives at the company had been worried about such an outlandish idea, but Johnston was not just a great record producer, responsible for Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen, The Byrds and Simon and Garfunkel – he was also a maverick who liked taking on the bosses and getting the better of them.

Cash, smelling a chance to put his prison notion forward again, to ears that might listen this time, took his opportunity and Johnston went for it.

Just weeks younger than Cash, Johnston was a Texan whose mother had written songs for Gene Autry and he was a man who, according to Leonard Cohen, knew how to turn the studio into a home-from-home, where musicians could relax and give their best.

Even if “home” was a crowd of entertainment-starved, scary-looking prison inmates.

At Folsom Prison was a triumph, and they hung on Cash’s every word, every move, every drop of sweat. Listening to it today, many would give up a year or two behind bars just to have been there.

He started, of course, with Folsom Prison Blues and the version of Jackson with June Carter singing harmony got a huge roar of approval, too.

If she was nervous with all these incarcerated gentlemen, who had not seen a woman in quite a while, staring at her, her voice did not waver.

Luther Perkins, who was on guitar alongside Carl Perkins, no relation, had just the right look for such a gig – rarely smiling, deadly serious, intent on his instrument, Johnny liked to joke: “Luther’s been dead for years, but he just doesn’t realise it.”

With such consummate musicians and the ideal singer beside him, Cash roared through his set and the entire thing was a huge triumph for him.

Little wonder he was so keen to do another, this time at San Quentin.

This time, he ended his set with Folsom Prison Blues and he pulled off the impossible – it was even better than At Folsom Prison and sold huge amounts of records.

I Walk The Line – a storming version – and A Boy Named Sue were standouts, as was San Quentin, which he had to do twice as they loved it so much.

The question was, with such all-conquering days just passed, would the 70s love Johnny Cash as much as the previous decades had?

Where would The Man In Black fit in with an era where men wore high heels and mascara and sang about spacemen, or London lads in ripped jeans yelled about anarchy and sniffing glue?

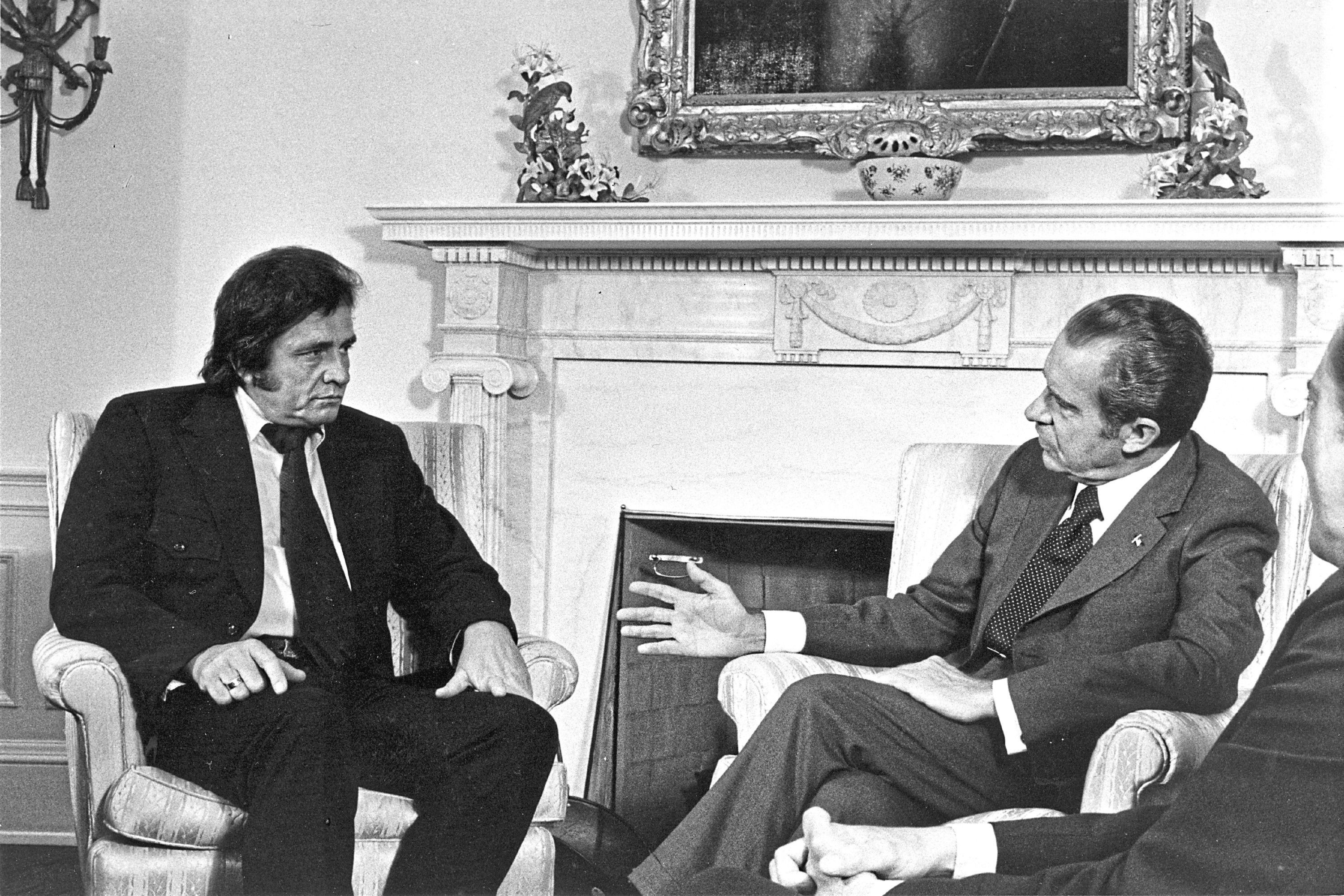

He was such a big name by the 70s that one day he might be meeting President Nixon to discuss prison reform, the next he might be making a movie about Jesus or protesting about the treatment of US soldiers in Vietnam.

The Johnny Cash Show was a huge US TV hit and everyone from Neil Young to Louis Armstrong would appear as guests. Cash even talked the reclusive Bob Dylan, a neighbour, into doing more public appearances.

Kris Kristofferson’s waning career got a huge boost from his appearances on the show and even if Johnny did get into amphetamine use again in the late 1970s, life was pretty good.

Sadly, as he got older and the pop and rock worlds got younger and more outrageous, Johnny Cash began to go through a bit of an old-fashioned phase.

His older fans still bought the records and watched the shows, but he wasn’t on top of the heap as he had been.

Fighter that he was and with a voice that was awesome at any age, he would be back making extraordinary records in the last years of his life.

In the meantime, though, he had the 80s and more recent decades to get through and Johnny would also have to face up to more battles in rehab against drugs in the 1980s and 1990s.

He would still pop up on TV and many loved his roles in such shows as Little House on the Prairie and Dr Quinn, Medicine Woman.

US Christmas specials would see him appear for some of the year’s biggest telly audiences, too and the studios knew they could always rely on Johnny Cash to make folks stay tuned.

Another US President who would become a close pal was Jimmy Carter, who was actually a distant relative of wife June.

You can safely assume that Johnny bent his ear with plenty advice on how to help the poor, the Native Americans and whoever else he felt needed assistance.

The year 1980 saw a very proud moment, when he became the youngest living inductee into the Country Music Hall Of Fame at 48.

He would also tour with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kristofferson as The Highwaymen and there was a memorable appearance on The Muppet Show.

The Man In Black and the green frog, face to face. It was a surreal success, of course and it was always funny to see that Johnny Cash didn’t actually take himself too seriously.

When in 1988 he visited Waylon Jennings, recovering from a heart attack, his pal said Johnny should get himself looked over, too.

That idea ended with Johnny having preventive heart surgery, almost as if Jennings had sensed something needed fixing with his friend.

The 80s had also seen Cash grow angry with his record label, who he felt treated him as an invisible man – and he clearly believed he still had something to say as a musician.

He wasn’t wrong.

It was in the 90s, as the end of his remarkable life was looming, that he started recording stripped-back versions of his favourite songs, material from way back but also modern-day stuff.

American Recordings, released in 1994, had been recorded in a living-room and in Cash’s own cabin, back-to-basics stuff, as raw and uncomplicated as a first demo tape by a kid.

It was a sensation, gaining him a huge new audience of younger folk as well as thrilling his older fans. Incredibly, it was his 81st album release and right up there with the best.

No wonder he had been frustrated with his old record company, with all this still in him.

From now until his death, he recorded similar albums at a frantic pace, almost as if he was in a race against time to get it all on tape before he left us forever.

Unchained came next, featuring I’ve Been Everywhere and a wonderful version of Memories Are Made Of This.

The talk of the music world was the incredible, gutsy comeback of one of the old men of rock and Cash must have felt thrilled to see how these albums were being lauded.

Solitary Man, including a version of U2’s fantastic song One, Tom Petty’s I Won’t Back Down and the traditional Wayfaring Stranger, only built on Cash’s remarkable comeback, just as everyone thought he was yesterday’s man.

The Man Comes Around saw him tackle songs by everyone from The Eagles to Depeche Mode, all in this new, sparse style, just a piano or a guitar backing him.

If his voice sounded old, tired and wise, well, that’s how he was. Johnny was 70 now, but putting out stuff the teens could not dream of matching.

There was more to come, some released after his death on September 12 2003, all of it proving once again how special The Man In Black had been.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © ITV / Shutterstock

© ITV / Shutterstock © White House Photo Office/PhotoQuest/Getty Images

© White House Photo Office/PhotoQuest/Getty Images © Beth Gwinn/Redferns

© Beth Gwinn/Redferns