The long debate around Not Proven – Scotland’s unique third verdict – is again coming to a boil as calls for it to be scrapped escalate.

Campaigners are leading calls for a switch to a two-verdict system with First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said to be persuaded by the need for change.

Critics, including Rape Crisis Scotland, say the verdict has no logical or practical purpose and may be partly responsible for Scotland’s low conviction rate in rape and sexual assault cases, which the first minister has described as “shamefully low”.

But some leading lawyers argue that removing the not proven verdict would destroy the balance of the existing system, making it more likely that innocent people could be convicted.

With around a thousand cases a year “not proven”, including an average of 10 murders, around 100 attempted murders, and around 110 sexual assaults and rape cases, is it time for change?

Here, we ask the experts on both sides.

The bar must not simply be lowered, since every innocent voice from behind the jail wall shames us all

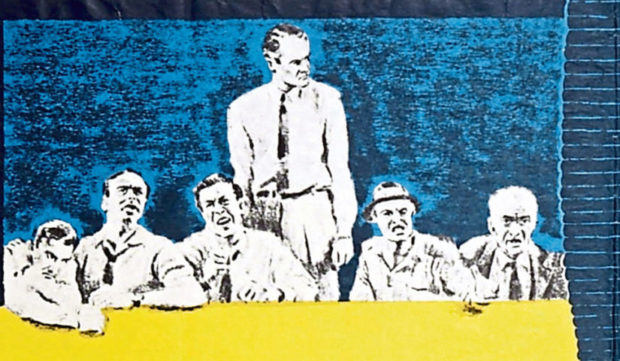

Ronnie Renucci, vice-dean of the Faculty of Advocates, warns against removing a verdict that, he believes, helps preserve fairness and balance.

He said: “Given the uniqueness of the Scottish jury system with 15 jurors, three verdicts and a simple majority to convict, it has long been recognised that the not proven verdict cannot be scrapped in isolation without other fundamental changes being made to the jury system, particularly in relation to the size of any majority required for conviction.

“It’s difficult to understand how not proven has become the scapegoat for decisions that, although unpopular with some, have been carefully considered by a jury who have had the benefit of hearing all of the evidence.

“It should not be forgotten that in cases involving allegations of sexual offences juries are the only members of the public who hear all of the evidence as the complainer’s evidence is heard in private.

“This time last year jury trials themselves were under threat. This year it is our not proven verdict. The more cynical among us would claim no surprise if next year it is the presumption of innocence itself under threat.

“If the not proven verdict is somehow seen as a barrier to conviction by some, then removing it is akin to removing a safeguard, and in a system where a simple majority can result in conviction such a safeguard is necessary.”

Tony Lenehan, president of the Scottish Criminal Bar Association, warns against lowering the bar to prove guilt.

He said: “People who may not be guilty of a crime must not be convicted of it. Our system of justice is predicated on that. When you lower the bar for proving guilt you will draw some people into jail who should not be there.”

A majority of eight out of 15 jurors is required for a guilty verdict. “Where is the nearest Western democracy with our mere 8/7 majority for guilty?” said Lenehan. “And yet loud voices want to lower the bar further.”

He said juries, rather than campaigners or commentators, were the best people to decide a defendant’s guilt or innocence.

“Juries are the ones who hear the evidence,” said Lenehan. “Who watch the witnesses. Who watch and hear the accused and the arguments.

“They are schooled by judges in this most important of civic responsibilities.

“Reading about a case filtered through the minds of journalists or bystanders or special interest groups does not equip you to criticise what that jury did, because they are in a better position than you to decide. The bar must not simply be lowered, since every innocent voice from behind the jail wall shames us all.”

“Our system of criminal justice has for centuries been regarded as a beacon to other civilised societies, and honoured in replication around the world.

“We live in times where every month seems to bring yet more restrictions of what an accused person is allowed to tell a jury. Lawyers trusted to keep the innocent out of jail feel and see a definite shifting of values against the accused.

“Let this debate eschew the dog whistle and let it be about exploring any improvement in communication from juries that keeps the innocent out of jail, and is proud to do it.

“Picking emotive cases as vehicles for cheap changes undervalues the world class refinement the centuries have wrought in our criminal courts.

“Every case is emotive in its own way, and from many viewpoints. Our system of criminal Justice has risen above the unbalancing pull of emotion for five hundred years, and juries the same.

“The voices for endangering those who are not guilty must resist the ‘comfort thinking’ of populism and equip themselves properly before they criticise a jury’s verdicts.”

Tony Lenehan, Scottish Criminal Bar Association.

It is illogical and has no place in a modern justice system. It simply leaves the jury bamboozled

After two decades as a High Court judge, Lord Uist is very clear that the not proven verdict has no place in a modern justice system.

He believes the third verdict simply confuses a jury, increases the possibility of a miscarriage of justice, and is illogical and lacking in common sense, and so a hindrance to justice.

Lord Uist said: “The Scottish criminal justice system is respected around the world.

“But nowhere else has adopted the not proven verdict for a very good reason – it has absolutely no place in a modern justice system.

“It is illogical, it lacks all common sense, and it should be abolished.”

The judge, now retired, said he spent 20 years telling juries there were two versions of acquittal.

He said: “As a judge, I was not allowed to define not proven to them.

“In fact, it is a legal concept which cannot be defined, the only one that I know of which cannot be.

“It’s something which simply leaves the jury bamboozled.”

“An accused person in Scotland is permitted to offer only one of two pleas before his trial – guilty or not guilty.

“No one has ever heard of an accused pleading not proven to a charge. Why should there be a verdict open to a jury which is not a plea open to an accused?” said Lord Uist.

“Juries who returned a verdict of not proven often thought that by doing so they were leaving open the possibility the accused could be prosecuted again on the charge and were amazed to find out later it meant no such thing.

“If there is no difference between a verdict of not proven and one of not guilty, what is the point of having the two verdicts?”

Defence QC Thomas Ross agrees Scotland’s criminal justice system needs only two verdicts, but not guilty or innocent. He argues not proven should be the alternative to proven.

He said: “It’s common sense to have just two. Having three verdicts can be confusing, particularly when the judge is prevented from explaining the difference between them.

“The function of the jury must be focused entirely upon whether or not the prosecution has proved their case beyond a reasonable doubt, or not, and that comes down to the quality of evidence and witnesses. We must be careful about getting embroiled in making this a political issue or one driven entirely by victims’ rights campaigners. It’s become a political football with even the first minister saying doing away with not proven could somehow improve the conviction rate for sexual offences.

“Rape and sexual offences are among the most difficult cases because of the quality of evidence available compared to a murder or serious assault where there may be many sources and witnesses.”

Campaigners fighting for justice for victims of crime are calling for not proven to be scrapped. Sandy Brindley, of Rape Crisis Scotland, says the not proven verdict is found disproportionately in sexual offence trials, with almost a third of cases receiving that verdict.

She said: “Scotland’s third verdict creates confusion, frustration and worsens what is an already incredibly difficult and re-traumatising process.

“Imagine coming to the end of a long, drawn-out process of seeking justice for sexual violence, only to be handed down a verdict that most people don’t understand, and doesn’t even have a clear meaning or purpose.

“Years of your life given to a process that doesn’t even have a conclusion. We know from survivors that this controversial verdict leaves more questions than answers. When it comes to one of the most difficult periods of their life, survivors need and deserve answers. We all do.

“It is not enough to pretend that this verdict gives some sort of comfort to survivors, when that is not what they are telling us and it is not what the research indicates.

“It’s not enough for those who favour the verdict to argue that it should stay because it’s always been this way. That is not a valid argument and it certainly doesn’t answer the question of why it is so overwhelmingly used in cases of sexual violence where we know that widespread public attitudes and misconceptions about rape and how people respond stand in the way of justice.

“Fundamentally this is about removing unjustified ambiguity from our justice system so that we can move forward with clarity and conviction.”

Domestic abuse campaigner Marsha Scott, chief executive of Scottish Women’s Aid said: “The not proven verdict disproportionately impacts survivors of gender-based violence.

“This is not only confusing for juries and the public but it leaves the survivor who has gone through this system and been scrutinised along the way, without any justice or certainty.

“As a country with the gold standard in domestic abuse law, we believe Scotland can do better.”

Sandra Brown OBE who, more than 20 years ago, founded the Moira Anderson Foundation in memory of the childhood friend she suspected was murdered by her paedophile father Alexander Gartshore, agreed.

She said: “Over the years we’ve supported thousands of victims of all kinds of abuse and violence, and I believe the three-verdict system leaves too much room for uncertainty in what the jury has really decided.

“Having just proven or not proven would make it much clearer and simpler for victims and juries. Three verdicts leaves too many victims of crime struggling in a limbo that’s impossible to resolve, leaving them with lifelong psychological distress and concern they weren’t believed.

“We believe the appointment of a new Lord Advocate and Solicitor General is an ideal opportunity for a whole raft of long overdue change, such as separating the roles from government and improving the system to ensure justice is more accessible to victims with far more rape and abuse cases actually making it to court.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe