Greig was sitting on his bed by the open window, blowing smoke towards the Ochils. He was in the year above me at school. We hadn’t been friends for long.

I had turned up at his door one day. His mum had died and I wanted to say I was sorry, that I knew what it was like to lose someone close, but it was also a strategic move. He was rumoured to have a lot of good albums.

“What’s this?” I asked.

He squinted, through the smoke, at the tape.

“Oh,” he said. “The Velvet Underground.”

I looked at the box. The titles had been written out, none too neatly, in blue ink. Sunday Morning. I’m Waiting For The Man. Femme Fatale.

“Are they French?”

“No.”

“Can we put it on?”

“No.”

We were listening to the Sisters of Mercy. We were always listening to the Sisters of Mercy.

“You can borrow it.”

I took it home. Didn’t bother to rewind. A song began. Spidery guitar then, gently, a beat, and then, a voice: weary, numb, stumbling, American – “I…don’t know…just where I’m going.”

Seven minutes later, in some hard-to-define way, life had changed. The song was Heroin. The singer was Lou Reed. It was unbelievably exciting, not just physically and emotionally, but intellectually, too.

The way the drums sped up and the strings screeched to suggest the effect of the drug – that was so clever, an idea you could feel in your brains and your veins.

It is a regrettable fact that there can only ever be one first time you hear The Velvet Underground. That was mine. I was 16. For a new generation, the moment may be about to arrive.

The Velvet Underground, by the American director Todd Haynes, comes to Apple TV+ and cinemas this month.

The two-hour documentary lingers on the band’s emergence from New York’s experimental filmmaking and avant-garde composition scenes of the early to mid-1960s, taking its aesthetic from those widdershins worlds.

The film, like the band, becomes more conventional as it goes along, but is in no hurry to get there. John Cale, three-quarters of an hour in, says: “The idea that you could combine R&B and Wagner was around the corner.”

Cale, now 79, is one of three surviving members of the group, along with the drummer Maureen “Moe” Tucker and Doug Yule, who replaced Cale in 1968.

It was Cale’s appetite for confrontational improvisation, matched with Lou Reed’s ability to conjure melody, that defined the VU sound. “As soon as Venus In Furs hit,” Cale says, “I knew that we had a way of doing something in rock’n’roll that nobody else had done.”

Venus In Furs is a shibboleth. If you get that song, you’re into the Velvets. Amplified viola and detuned guitars define its sound world, while Reed’s evocation of sado-masochism – “Whiplash girlchild in the dark” – is seductively transgressive.

It was recorded in Los Angeles in 1966, but that’s not what it feels like. That magnificent droning dread seems to be coming out of Paris in 1919, or Jerusalem during the First Crusade.

It irradiates the culture and has no half-life. It doesn’t matter how often you hear the song; doesn’t matter if it’s used in adverts or soundtracks. Venus In Furs never loses its power.

I remember driving across Rannoch Moor late one night and it came on the radio. Autumn darkness, the shining eyes of deer at the sides of the road, and that song. It had never sounded better.

“This was not just music, but a kind of drug,” Haynes observes in his director’s statement. “This was music that singled you out, identified you not only as someone who suffers and transgresses but who believes in it.

This was music that aroused creative desire. And somewhere within its cavernous sound an understanding that creativity itself comes, at least in part, out of subjugation.”

What he’s getting at there, I think, is that the narcotic and carnal explorations so associated with the group should not be regarded as subject matter, but rather as part of their creative core.

These aren’t songs about sex and drugs, these songs are sex and drugs, with all the pleasure and pain that goes alongside, in that they have the power to shape the identities and perceptions of those who experience them.

Brian Eno’s aphorism that hardly anyone bought the first Velvet Underground album, but everyone who did formed a band, does not go far enough in stating their impact.

They have had a clear influence on generations of musicians, writers, visual artists, fashion designers, filmmakers, thinkers and creatives of all sorts. But more than that: they have the capacity to change anyone who hears them, so that the world is forever tilted.

“I don’t know just where I’m going/But I’m gonna try for the kingdom if I can.” Those words are on page 36 of the book sitting on my desk as I write this. Pass Thru Fire contains the collected lyrics of Lou Reed.

“It’s a treasured possession. He signed it for me, and wrote a kind note, when we met in Copenhagen in 2005. I’ve interviewed hundreds of famous people over the years, but he’s the only one I think of as a truly historic figure, someone without whom the 20th Century would not have been quite the same.

“It is a war story – My Fight With Lou – in that he was as performatively hostile towards me as with most journalists he encountered. But it is also a love story; I had a chance to talk with and thank a songwriter whose work has enriched my life since the day I picked up that tape.

I told him about that experience, hearing Heroin in my teens and being impressed by the cleverness of it.

Yes, he said, but I must remember that, when it came down to it, they were a bunch of young musicians having fun. “We certainly did enjoy what we were doing and we were very pure.

“One hundred per cent devoted to music as music without any other considerations. That’s why it was great to be picked up by Warhol, who loved us just the way we were and didn’t try to change anything, except, y’know, give us a chanteuse.”

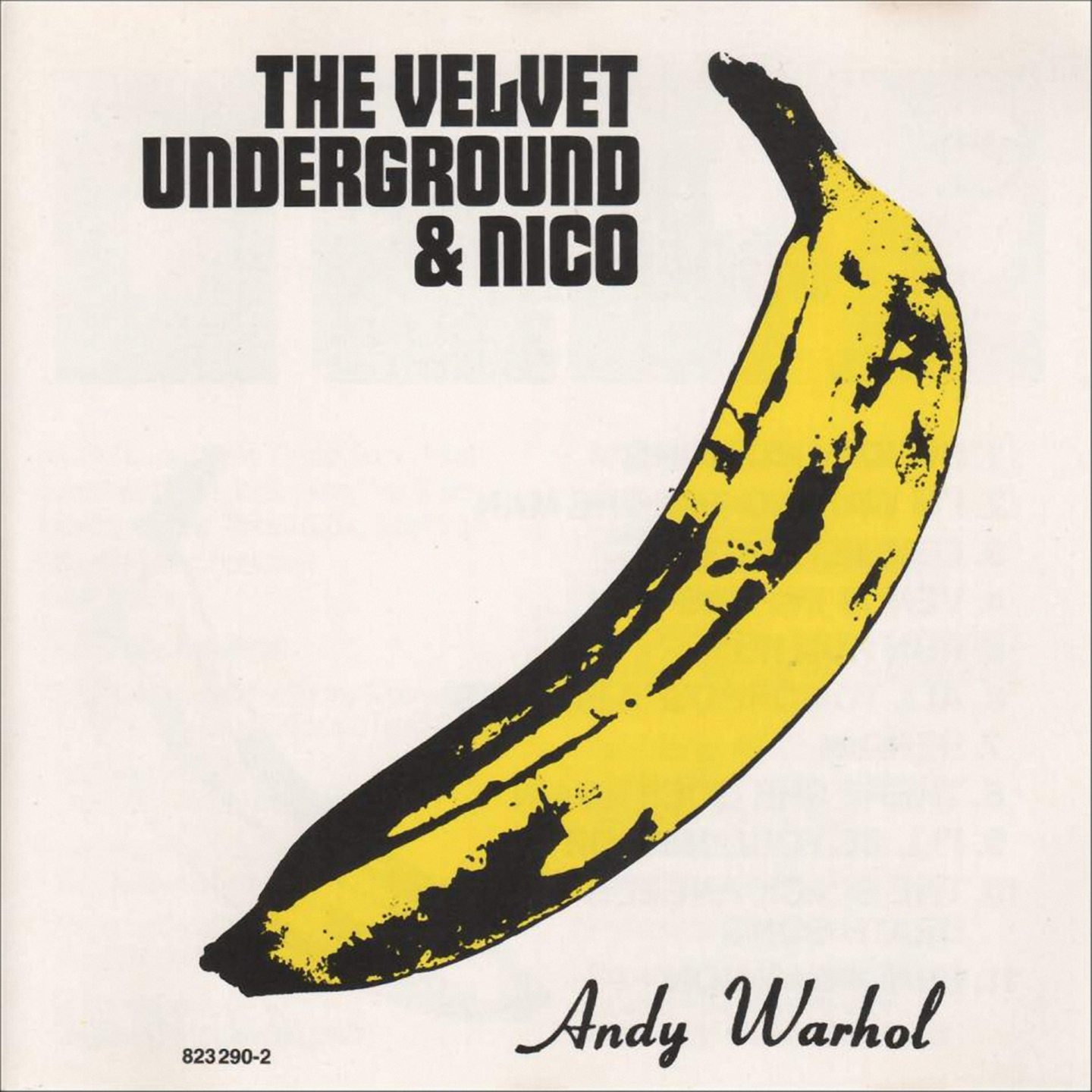

Andy Warhol managed the band between late 1965 and the summer of 1967, and created the classic banana sleeve of their debut album.

The chanteuse is Nico, the German musician, model and actress whose performances – Femme Fatale, I’ll Be Your Mirror and All Tomorrow’s Parties – gave that album a stately and dignified melancholy, as if to be anything other than sad would be a breach of etiquette.

She is too often seen as being a satellite of the Velvet Underground, a minor star in their orbit, or, worse, as some sort of mannequin over which the creations of the men were draped. In fact, Nico was a unique musician and performer who brought to the collective her own gravity and wounded grace.

“To me, this was like being in the presence of Michelangelo,” says Jonathan Richman, in the documentary, of his time as a teenage fan hanging out with the band.

That sounds like hyperbole, sure, but let’s also acknowledge the truth of it: the Velvet Underground were great artists and it is so exciting to think that there are people who are about to encounter, for the first time, the always beautiful, sometimes brutal art that they made.

I wish I could feel that rush and run again.

The Velvet Underground will be on Apple TV+ and in cinemas from Friday

It rocks but is so twisted. Raw power.

I am gone, flattened. The roar increases

In the first edition of his What Goes On fanzine, MC Kostek remembers the first time he ever saw The Velvet Underground in March 1969. He was 16.

“This next song’s called Heroin.” The thin figure dressed in black on stage looks nervously around. ‘It’s not, uh, for or against it. It’s just about it.’

The two South Deerfield, Mass., cops at the side entrances are momentarily distracted from their evening’s boredom (the only relief provided by teen drunks and gate-sneakers).

Now this weirdo with the black leather jacket and sunglasses is talking to them about heroin.

“This song’s been banned in San Francisco. Hope you like it.”

So imagine you’re a kid, and you’re at your second concert ever, and you’re sitting in 1969 with whatever there is of the small farming town area hippie slick of kids. These people with nasty clothes get on stage and BANNNGGO! Such noise!

This guy who sings funny is waving a guitar, another’s hunched over the keyboards unearthing some mighty odd sounds, another’s hunched over the bass, and the drummer, who looks like a woman, is playing with big mallets (the kind that kick the bass drum on regular kits), the better to bang her bass drum, turned on its side as a snare, with.

From the first screech, I’m transfixed. The songs, about waiting, love, call my name, all fly by in a vicious torrent. During the break, we dare each other to go chat with them. It’s tempting, but they’re too forbidding, and we try to relax.

A few buzzheads dance near the front of the stage, but the rest of the few hundred hipsters sit immobile on the floor, trying to deal with this howl. It gets late, and the “leader” says they’re going to do this story-song.

He kicks out this riff, and while things before were intense, they are now erupting, they slowly build, and begin to fly. The singer’s yelling something about his “ding-dong” and they kick into a harder, faster wail.

The singer’s hand is a blur, stroking and making this 12-string shudder and scream, the bass player’s got another guitar and is ripping up on that, the organist is leaning, slapping the keys.

And the drummer – not only has she stood all night, but she’s pounded steadily with those big mallets all the while, raising one up over her head for the big BAMP-BAMP-BAMP. Steady. I’m not quite sure how long this went on.

It seemed a half-hour – but time, space, meant nothing. I was gone, flattened by the raw power. It rocked but it was so twisted. The roar increased, then built until I could hardly stand it.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe