A 97-year-record for the biggest rod-caught salmon in Scotland will never be broken as their numbers have plummeted, experts warn.

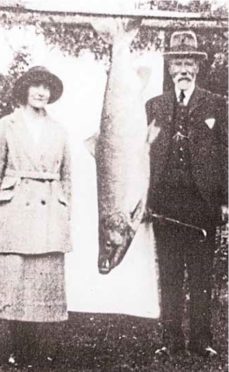

Ghillie’s daughter Georgina Ballantine entered angling legend in 1922 when she landed a 64lb salmon on the River Tay.

But experts fear the chances of such a fish ever being caught again have dwindled to nothing as salmon numbers suffered catastrophic decline.

Last week, we assembled an international coalition of experts to demand Scottish Government ministers urgently implement a range of practical measures which could ease the threat to the iconic fish.

Environment secretary Roseanna Cunningham was urged to “bang heads together” to secure plans to protect wild salmon.

Documentary-maker Will Millard, who attempted to break Miss Ballantine’s record while writing a book about fishing, said: “I love the fact it’s a woman who holds this record.

“The fish was extraordinary. It was 64lbs. We will never see a fish that big ever again.

“I’m pleased in a way she’s going to hold on to the record as the story of the capture is so iconic and romantic.

“Equally, it’s a tragedy that we’ll never see the likes of those big fish again.”

Scientific studies have shown that the number of wild salmon is in catastrophic decline and also that the proportion of large fish has dropped significantly.

Professor Craig Primmer, from the Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences at the University of Helsinki, was involved in a study which found that evolution was driving the species to become smaller.

Salmon migrate out to sea from their home river, spending up to five years in the marine environment.

The fish need to spend years at sea to have a chance of growing to impressive weights which would have a chance of coming close to the 1922 record-holder.Mature fish are now outnumbered by younger salmon, known as grilses, which have only spent one year at sea before returning to their home river to spawn.

The number of older salmon in the southern region of the north-east Atlantic, including around Scotland, fell by 81% between 1971 and 2010. Grilses numbers fell by 66%.

Overall, numbers have fallen by more than half in the same period but, in Scotland, the proportion of grilses increased by 86% while the multi-sea-winter salmon decreased by 42%.

Prof Primmer said the changes made evolutionary sense for the species as the longer they spent at sea, the more likely they were to die before they could return to their home river to spawn.

He said: “These fish that are getting up to more than 40lb will have spent at least three years at sea.

“What’s been changing over recent decades is that, overall, the abundance of salmon has been decreasing.

“So the number of salmon in the sea and returning to spawn is decreasing.

“In addition, the proportions of fish returning that have spent many years in the marine environment, the multi-sea-winter fish, are decreasing. So you’re seeing a much higher proportion of grilses than of salmon in the fish that are returning.

“That means you have a much higher number of the smaller size.

“I wouldn’t bet someone is going to catch a fish of 64lb or more in the near future.

“At the same time, I would never say never. The odds would be pretty low.

“If there was a concerted effort to make sure the conditions in the river were as optimal as possible for salmon and that potential risks in the marine environment were reduced as much as possible, then it’s not impossible for the large salmon to return.

“But at this point in time it seems that from an evolutionary perspective it’s a much more sensible strategy to be a small salmon than a large salmon.”

The Scottish Government says it is committed to protecting wild salmon and is waiting for comments on a draft plan to the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organisation which should be finalised by November.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe