It was the storm of storms, with towering 50ft waves and raging winds of up to 128mph destroying homes and knocking out roads, railways and power stations.

More than 2,000 people from Scotland, Ireland, England and the Netherlands would lose their lives in the North Sea Flood of January31, 1953.

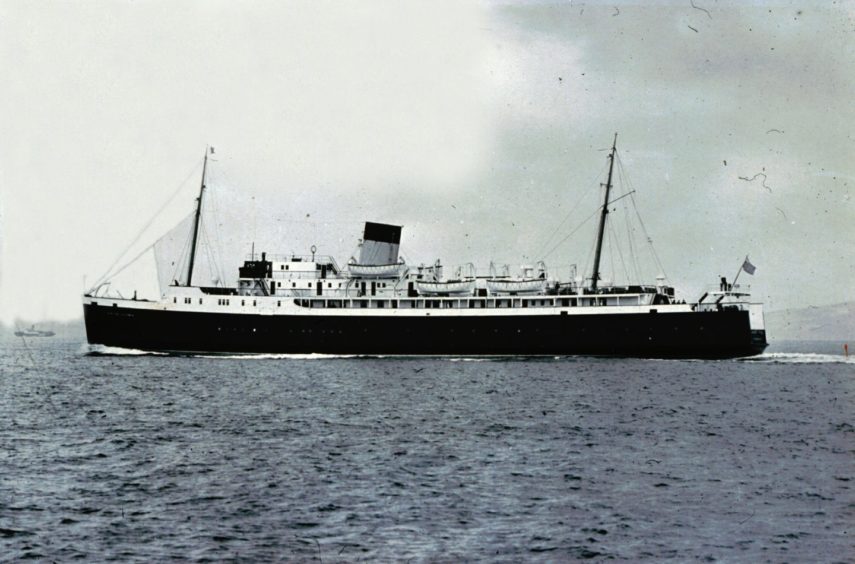

On Scotland’s south west coast The MV Princess Victoria ferry from Stranraer to Larne sank in the North Channel with the loss of 133 men, women and children, the biggest peacetime maritime disaster in British territorial waters.

The cause of the devastation was a deep Atlantic depression that had moved south-west to join gales and high spring tides off Scotland’s north coast, sparking huge tidal surges.

The cost of the damage was £50 million, the equivalent of more than £1 billion today.

Here, as the anniversary of the tragedy approaches, The Sunday Post remembers the catastrophic storm.

They lived together, worked together, died together and are buried together in a line

From his lounge, James Ferguson can see the sea that claimed the life of the grandfather whose name he bears.

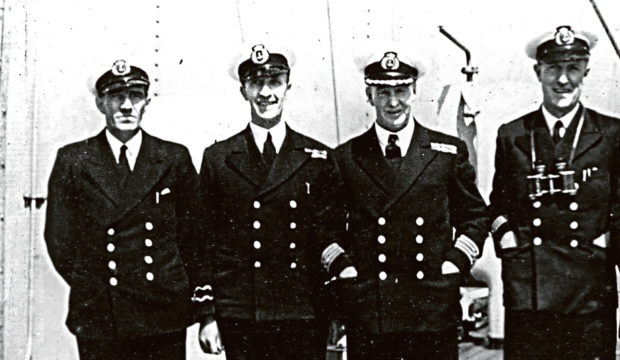

Captain James Ferguson, skipper of the Princess Victoria, was last seen standing at salute on the ferry’s bridge in the moments before it sank beneath the waves. She was only five miles from safety.

Mr Ferguson, 54, who was born after the tragedy, said: “It is quite hard to understand how a ship got into trouble so close to port. That was what most upset my late father Jim, an accountant. He did not speak about it until later years. He told me he had been at a football match in Glasgow and saw the disaster on the newspaper hoardings. My dad said he missed his father every day. He was 18 in the year of the storm and 81 when he died in 2015. It never left him.”

Each year the head teacher and dad-of-three attends a service of remembrance at the Stranraer memorial to the victims. Other memorials are in Portpatrick and Larne.

His grandfather’s home overlooked the harbour where the 55-year-old’s neighbours included his chief officer Shirley Duckels and radio officer David Broadfoot, who was posthumously awarded the George Cross for his bravery in the disaster. Like all those on duty on the bridge that day, none survived.

Stranraer historian Jack Hunter, 87, said: “It is tragic. They lived together, they worked together, they died together and are buried together in a line at Inch churchyard two miles from Stranraer.”

The author of The Loss Of The Princess Victoria, published by Stranraer & District Local History Trust, said no women or children were among the 44 survivors.

Of the 49 crew on board, 19 from Stranraer and 20 from Larne drowned.

His account tells how soon after leaving the shelter of Loch Ryan the skipper tried to turn back but the sea ripped off the rear doors to the cargo deck, flooding it with water. Continuing to present its stern to waves would have been disastrous. A desperate bid to take the vessel home in reverse failed and it appeared the captain had little choice but to attempt to nurse the stricken vessel, one of the first roll-on, roll-off ferries, on to Larne.

Mr Hunter said: “The Victoria was on a 20-mile route. Had it been a clear day she would have been in sight of land the whole time. Yet she got lost and sank.”

Today, Mr Ferguson looks out to sea and remembers his grandfather: “Sometimes I walk along the shore and allow the water to flow around my feet. It is strange to think it is the same water that took my grandfather all those years ago.”

The captain was on the bridge, at salute, as the ship rolled over

Courageous radio officer David Broadfoot sent the first distress message in Morse code shortly before 10am on January 31, 1953. Four hours later the ferry rolled over and sank. The loss of her radar in the storm and misunderstandings over her position meant help did not arrive until 50 minutes after she went down.

“It must have been a day of stark terror,” said historian Jack Hunter. “Conditions on board, especially for the last hour and a half, were horrendous. The Victoria at that point was virtually on her side. The radio operator was standing on the ceiling to send out his SOS messages. She lost electricity and was in semi-darkness towards the end.

“People were being sick. It’s reckoned that quite a number simply gave up, went to their cabins and waited their fate, numbed by the horrors they were witnessing. She went over slowly with many people jumping on to rafts, into lifeboats, or into the water. Some brave souls clambered over the port guardrail as the ship rolled and ran up the hull. Then, as she turned turtle, made their way along the keel before jumping for safety.”

The skipper and wireless operator were not among them.

“Captain Ferguson was seen on the bridge at the salute as the ship rolled over while David Broadfoot made no attempt to leave his wireless cabin. The time of his last message, 13:58, was almost exactly when the ship keeled over.

“She lingered for a few moments, long enough for one of the three lifeboats launched to be smashed against her by a wave and the occupants thrown out, and then sank.”

According to Mr Hunter, an inquiry ruled the ferry’s loss was due to the inadequate strength of her stern doors and the lack of sufficient scuppers on the car deck to clear the water. The ship’s owners, The British Transport Commission, and her London-based manager were held responsible.

I remember it took just three waves to knock one house down. It was total devastation

The fearsome storm also caused devastation on land and the Moray Firth fishing villages of Gardenstown and Crovie were among the worst hit on Scotland’s north east coast.

Coastguard’s daughter Eleanor Hepburn, 79, was 12 when the storm struck and watched the drama unfold from the safety of her home, high above the harbour.

Great-grandmother Eleanor, founder of the Gardenstown Heritage Centre, revealed with the help of her former headmaster James Slater’s school log entry, how the “waves were the biggest ever seen”.

She said: “The boat building yard used to store wood. I remember looking out and seeing huge planks sailing across the road into the harbour. A lot of the sheds at the harbour were washed away and the seawalls were broken down. It was total devastation.

“There were two houses together right at the end of the village that were both destroyed. It took only three waves to knock one of them down.

“Friends who lived in Crovie came and stayed with us that night because their house was completely washed out inside.

“We went to see it the next day, it was like stepping on to a beach. It was covered in stones and sand.

Gardenstown resident Maureen Reid, 77, was nine when the waves came crashing down on the cottage she shared with her parents 12ft from the sea. She had to be rescued through a skylight. The retired nurse and carer remembered: “We thought we hadn’t a hope. We had no windows at the back of the house but there was a two-foot wide skylight in the eaves. My dad put a big plank of wood across it, tied a rope around it and around me, and lowered me out. Waves were coming over the roof. I was soaked.”

Neighbours waiting at the top of a lane that ran alongside the house ran down to catch her. Her parents then made a parlous escape.

Maureen Watt, 79, lived with her grandparents at No 55 Crovie – the highest point in the village. She recalled: “The waves were coming up and round about the house and the water was coming down the chimney, it was that bad.

“I remember my granny standing beside me, saying, ‘It’s alright now. The Lord will look after us.’ She must have been afraid. A lot of people left Crovie after the storm and didn’t return.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Alamy

© Alamy

© NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED

© NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED © NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED

© NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED