It seemed an unlikely resting place for one of the ancient world’s most esteemed rulers.

But, in a curio museum beside Niagara Falls, after being plundered from his tomb, bought by a Scots doctor for £7 and gifted to a friend, the mummified body of King Ramses I, the founding pharaoh of ancient Egypt’s 19th Dynasty, became an attraction for gawking tourists.

His ignoble fate, discovery and repatriation is among the stories charted by Maria Golia, in her book, A Short History Of Tomb-Raiding.

Once buried underground to ensure a bountiful afterlife, the beauty and mysticism of the treasures unearthed from Egyptian tombs have fascinated us for centuries. Yet, it often wasn’t archaeologists who first uncovered ancient artefacts like highly decorative coffins, gilded death masks, or even royal mummies, but thieves.

“Almost everything we know about Egypt comes from tombs, because they had this religious tradition of burying people with riches and objects they would use in the afterlife,” said Golia, an American with a passion for Egypt, ancient and modern.

“All of the collecting for museums that took place in the 1800s was done with the assistance of Egyptians. In many cases, this meant tomb raiders. They needed to make a living, so whatever they found they sold. And that’s how these artefacts were spread around the world.”

These included the mummy of King Ramses I, which now lies in the Luxor Museum in Egypt after spending 150 years as a nameless exhibit in the US until it was identified and returned to Egypt in 2003.

James Douglas was a Scots physician who made multiple visits to Luxor (formerly Thebes) in Egypt during the 1860s. There he met Mustafa Agha Ayat, vice-consul for Britain and America in Luxor. Ayat also enjoyed a lucrative side hustle, trading in antiquities stolen by the notorious Abdel Rasul family who raided tombs across the Theban Necropolis – a huge burial site that included the Valley of the Kings, Valley of the Queens and Tombs of the Nobles.

“Douglas purchased several mummies from Ayat,” said Golia. “He kept two for

himself and sold the third, a fine mummy in double cases that he bought for £7, to a friend, Thomas Barnett, who ran a curio museum in Niagara Falls. The mummy sat there for 150 years next to Sitting Bull’s moccasins and a two-headed calf, and later moved around local museums advertised as Nefertiti.

“One day an Egyptologist examined it, looked under the loincloth and said that was definitely not the case! Not only was the mummy male, it had its arms crossed in a position typically reserved for royal mummies.

Other Egyptologists agreed it was royal and, because of the timing, where it was bought and from whom, they suspected it was the missing mummy of Ramses I.”

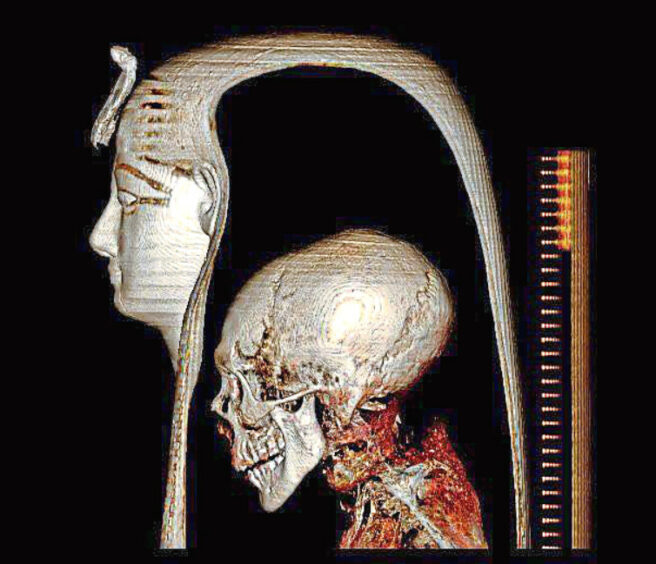

By this time, the mummy was owned by a museum at Emory University in Atlanta. Further CT scans, X-rays, skull measurements and radiocarbon dating tests carried out by researchers suggested it was most likely Ramses I, whose short reign ran from 1292 to 1290 BC. He was also grandfather to Ramses II, often regarded as Egypt’s greatest ruler.

“It was big news at the time,” said Golia of Ramses I’s repatriation to Cairo in 2003. “There was a lot of fanfare surrounding the long-lost king returning home.”

Tomb raiding is an age-old crime that Golia’s book tracks from antiquity to just before the Egyptian Uprising of 2011.

“The raiders of Gurna were burrowing in tombs that had already been pillaged non-stop for 3,000 years,” she said. “At one point, there was so much theft, with temple and palace officials in on the take, that the wealth being recovered from the graves actually became the basis of Egypt’s economy.”

The ancient Egyptians understood that burying their wealth underground would attract grave robbers, and took both practical and mystical precautions against theft. This involved less giant boulders and more clever architecture, with a few spells and booby traps thrown in for good measure. “Architects would booby-trap shafts to pour sand when opened, install dead ends, shafts leading to fake doors, dummy doors and huge granite plugs designed to fall and block a shaft. But the raiders were experts and could avoid those obstacles by tunnelling from elsewhere. Areas of a necropolis could become so crowded that they could tunnel from one tomb to the next undetected,” said Golia.

“There were also magic spells and curses that would await those who defiled the tomb.”

The discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 fuelled a renewed interest in Egypt and also gave rise to the myth of the “mummy’s curse”, despite the fact no one present at the opening of his tomb met a swift and gruesome fate.

Superstitions held by grave robbers in Egypt varied according to their beliefs, noted Golia. “In medieval times, following the Arab conquest of Egypt around 640, indigenous Christian Egyptians had an interest in counterbalancing that magic. They would use incense and incantations because there was a strong belief in the supernatural and they were trying to fight fire with fire.”

Some early raiders were privy to inside knowledge of treasure-laden tombs, Golia added. “There was a police guard in the necropolis called the Medjay but they couldn’t be everywhere and might even be on the take. Those who helped build and decorate the tombs swore an oath of secrecy but not everyone honoured it, especially when they saw all these riches buried while they weren’t living as well-off as those in power.

“There are parallels in tomb raiders’ motivations today: the greed, the desperation, and also rebellion. These riches weren’t buried for fun but to ensure their place in the afterlife. The notion of eternity was sacred. The raiders weren’t just thieves, they were breaking every law in the books about how to live in a way that would see you enter the afterlife. So they were transgressors in a big way.”

Among Egypt’s most infamous grave robbers were the Abdel Rasul family, described by Golia as an “Egyptian tomb-raiding dynasty”. They cemented their place in history in the early 19th Century when they discovered the Royal Cache of more than 40 royal mummies hidden in the Tombs of the Nobles.

“That was strange because usually royal mummies were buried alone with all their riches. Several thousand years before, priests had moved the mummies to one place because theft was rampant. Then, 3,000 years later, the raiders got to it in the end,” Golia explained.

“The Abdel Rasul family lived in the Tombs of the Nobles. It was their home and hunting ground as they traded the antiquities they found. One day, they made this incredible discovery of these important ancient pharaohs like Seti I and Ramses I, buried in these beautiful, human-shaped mummy cases that were around four metres high, and surrounded by countless artefacts. The Abdel Rasuls started selling the artefacts, including Ramses I.”

The beginnings of Egyptology and the study of hieroglyphs proved their undoing. “They didn’t realise Jean-François Champollion had discovered how to decipher hieroglyphics, so people could read the names on these artefacts. The Antiquities Service eventually realised they were seeing the same names pop up and realised someone must have discovered a royal tomb. The most likely suspects were the Abdel Rasuls. The authorities caught them because the tomb raiders couldn’t read hieroglyphs but the archaeologist could.

“The older brother cut a deal with the authorities that he would show them where the cache was if they let the family off and gave him a job, ironically, as a guardian of the Theban Necropolis.”

Golia, who resides in Cairo, became interested in the history of tomb raiding when she heard of houses in the city collapsing for an unusual reason. “In 2007, I read about houses collapsing because people were tunnelling underneath them looking for treasure, which I thought was strange,” she said. “Then I discovered they’ve been doing this all this time.”

Rather than exalt the daring heists or priceless finds of tomb raiders across the centuries, Golia is more interested in the impetus behind grave robbers stealing and trading their country’s artefacts.

“Essentially, this was happening when Egypt was economically in a bad place because of the global downturn; the Suez Canal was not doing well, tourism was not doing well, so people were hurting,” she said. “I wondered if the two things were related; when Egyptians are broke, do they grab a shovel?

“Satellite imagery of Cairo and the surrounding desert suggested an uptick in theft during this economic time, in the same way it was around the Uprising of 2011, when security was lax. In Egyptology, periods when central government breaks down are called intermediate periods; times of unrest and uncertainty, when there are also more thefts. I went back to the very beginning to understand that connection.

“Tomb raiding has been going on for thousands of years and, while security is a lot tighter in Egypt these days, there are some who are swayed by these stories and are out there looking for the jackpot.”

Warrior king had great teeth: Scans shed light on mummies

The discovery in 1881 of the resting place for more than 40 royal mummies at Luxor, including some of the greatest pharaohs in history, was celebrated across Egypt.

Yet the authorities faced a problem – how to move the mummies and countless artefacts before they were stolen.

The Egyptian government sent Émile Brugsch, head of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, to oversee their safe delivery.

Coming face to face with enormous mummy casks that held Egypt’s greatest rulers, surrounded by piles of ancient artefacts, was a jaw-dropping moment. Brugsch later wrote: “Collecting my senses, I made the best examination of them I could by the light of my torch, and at once saw they contained the mummies of royal personages of both sexes. Their gold coverings and polished surfaces so plainly reflected my own excited visage that it seemed as though I was looking into the face of my own ancestors.”

It took more than 300 men three days to move the artefacts from their tomb to a boat headed for Cairo.

“Their minds were blown by what they found,” said Golia. “Yet they realised they had to get it out of there as soon as possible before it was stolen. So they hired men to help in this tremendously laborious process to remove the artefacts from the tomb, wrap them in straw matting, then carry them two miles across the floodplain to the Nile, then across the river and on to the museum steamer that would take them to Cairo.”

Custom officials were perplexed with how to process this unusual cargo: “When the museum steamer arrived in the port of Bulaq in Cairo, customs officials were perplexed about how to classify the mummies because there was no category for importing such a thing. As the Egyptians are slavish bureaucrats, they had to classify it somehow, so they classified it is dried fish.”

Eventually, the haul made it to the Egyptian Museum where the mummies were examined and placed on display. Exhibits like the mummy of Seti I, found in the cache, can still be seen in the museum today.

The mummies found in 1881 included that of warrior king Pharoah Amenhotep I. Last year, X-ray scanning revealed fresh details about the ruler when radiologist Sahar Saleem said: “We show that Amenhotep I was approximately 35 years old when he died. He was approximately 5ft 6in, circumcised, and had good teeth. Within his wrappings, he wore 30 amulets and a unique golden girdle with gold beads.

“Amenhotep I seems to have physically resembled his father…he had a narrow chin, a small narrow nose, curly hair and mildly protruding upper teeth.

“Mummified bodies were well preserved. Even the tiny bones inside the ears were preserved. No doubt Amenhotep’s teeth were well-preserved. Many royal mummies had bad teeth, but Amenhotep I had good teeth.”

A Short History of Tomb-Raiding: The Epic Hunt For Egypt’s Treasures by Maria Golia, Reaktion Books

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Salah Ibrahim/EPA/Shutterstock

© Salah Ibrahim/EPA/Shutterstock