Standing outside the flat of the friend she had not seen in two decades, Tracey Thorn began to wonder if she was doing the right thing.

The musician turned author – one half of indie favourites Everything But The Girl – had been 20 and shy when she first encountered Lindy Morrison.

Meeting the drummer from The Go-Betweens, a “big, loud, force of nature,” backstage at London’s Lyceum in 1983 would begin one of her most important friendships, an unbreakable bond forged in a music industry dominated by men.

When Morrison eventually left London for her native Australia, their connection became a long-distance affair punctuated by letters, and later social media, but contact slowed and then, eventually, stopped.

Then Thorn, 58, decided to write about her old friend, to pay tribute to a wonderful character, a larger than life personality and accurately portray her role in a seminal band which, her old pal believed, had been underplayed for far too long.

She flew around the world to her friend’s home to discuss her book but, she laughs, the welcome she got was not what she expected although, in hindsight, it should have been.

Thorn – whose partner, Ben Watt, 58, is the other half of Everything But The Girl, and father of their three children, twin girls Jean and Alfie, 23, and son Blake, 20 – said: “I flew out to Australia in August 2019. At that point we hadn’t seen each other in 20 years. So that was scary. I remember being on the plane and thinking, ‘This is a massive leap. Supposing I get there and feel like we are not really friends any more, or I don’t really know her.

“So I get to her flat and she throws open the door to me. I’m expecting she’ll say, ‘Oh my God Tracey, I haven’t seen you for so long! How are you? Come in. Let me make you a cup of tea.’

“Instead she opens the door, picks up a skirt, holds it out to me and says, ‘Hi Tracey do you want this? It doesn’t fit me any more. It makes me look fat. You could try it on.’

“I stood there with my mouth open going, ‘Wait, what? That’s your opening line to me?’ It was so Lindy. I had forgotten that she just doesn’t do the niceties and small talk.

“We had a morning of slightly awkwardly trying to get back on each other’s wavelength but within a couple of hours we really had. I had forgotten that she doesn’t do the boring bits and just cuts to what she’s thinking. She is unpredictable, funny, you don’t quite know what she is going to say next. I found myself remembering that and being delighted by it all.

“On that first morning in her flat, she suddenly pulled out a box. She had kept all my letters. That was quite emotional,” Thorn admitted. Not least because she had kept Morrison’s letters, too. Their correspondence – and diaries – are an integral part of Thorn’s new book My Rock’n’Roll Friend but London-based Thorn, – who is appearing online at Glasgow’s book festival Aye Right! later this month, stresses it is not a biography, more her take on the life and times they shared, surviving and succeeding in one of the world’s toughest and most sexist industries.

It’s a vivid, sometimes funny memoir, pulsating with energy and purpose – to expose the double-standards and hypocrisy of a business for too long dominated by men.

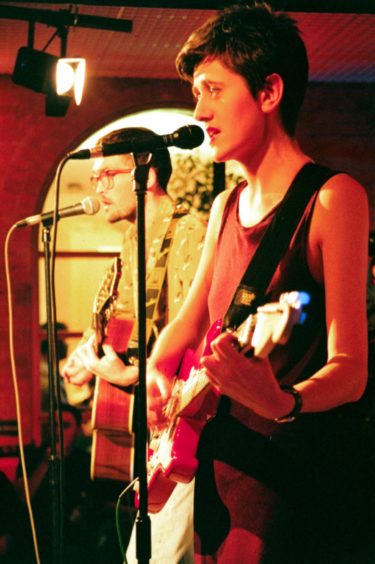

Thorn – who started out with the Marine Girls, before forming Everything But The Girl with Watt while at university and which in its 17-year duration landed nine gold and two platinum albums – remembers her first meeting with Morrison. Thorn was just starting out and feeling “lost and lonely” that day. There were troubles in the Marine Girls, and she’d had her first run-in with road crew. She was close to tears when Morrison breezed in asking for a lipstick and looking like “self-belief in a mini-dress, the equal of anyone.”

“I was at that stage in life where I was trying to work out who I was going to be and she seemed like someone who could be a role model.

“When we became friends we both had that experience of being women in the music business, where we were often the only women around. At gigs the crew would all be men, or at a record company the A&R people were all men. So we recognised in each other that sense of being allies in this world.

“And she had the added obstacle of being a woman drummer. Which again was really quite unusual at the time. She would turn up at gigs and roadies would assume she didn’t know how to put her kit together.

“It’s hard enough being taken seriously in the music industry as a woman, but when you are a drummer it is so physical – callouses on your hands, it builds up muscles in your arms and when you are playing you are really sweaty. That was not considered feminine back in those days. It’s that question of trying to convince people that you can do these things and still be a woman and be taken seriously in the same way a man would be.”

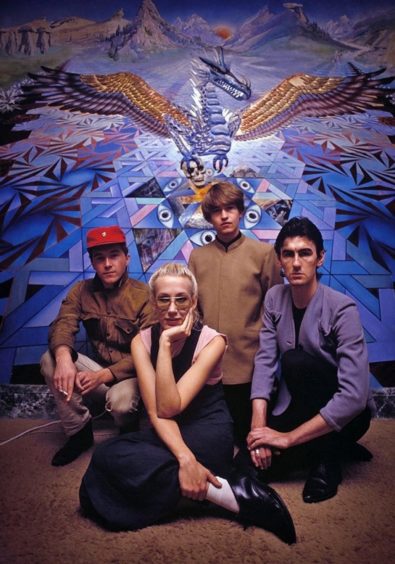

Morrison was a social worker, part-time actor and drummer for jazz and punk bands when she met Go-Betweens singer Robert Forster in 1979, started a relationship and joined his band. Along with guitarist Grant McLennan, they started recording their first album and it still tickles Thorn to think the guys thought she would soften the band’s image given that Morrison was “as soft as a right hook.”

Thorn remembers in the book how Morrison struck fear into male interviewers when she challenged their sexist assumptions. And she shines a light on how, in the re-telling of the band’s history, despite being a brilliant musician, Morrison’s role is diminished. Morrison split up with Forster in 1986 and three years later was dumped by the band. In 2016 Forster published a book telling its story but titled it only “Grant And I”. A documentary on the group, Right Here, came with the subheading “Three Decades. Two Friends. One Band”. So where was Morrison?

“Her role has got smaller and smaller,” Thorn said. “When I started writing the book I wasn’t aware that that was going to be part of the story. But the more research I did, the more I just kept coming across reviews, and then I read Robert’s book, and then I saw the documentary, and in each instance it felt like her role either got smaller, or it became one-dimensional.

“She kept being turned into the villain. She would be responsible for bad feeling that led to the break-up of the band, or a bad incident would be recounted that showed her in a really bad light when I felt the guys in the band were just glossing over things that showed them in a bad light.”

To Thorn it felt like “the focus had been skewed” and she wanted to offer another perspective.

“When Lindy joined the band, she made them more exciting. There was a kind of tension. She brought her massive personality to the group. In a way, to diminish her doesn’t do the band any favours.”

Embracing her friend in her entirety has helped form the woman Thorn is today. “When I met Lindy I was searching for female role models in music. She was pretty much my opposite in many ways.

“I didn’t think I could live my life in the way that Lindy does. She just managed to show me alternatives. And I took inspiration from her outspokenness, her refusal to be cowed in an interview if she was being either ignored or spoken down to.

“Maybe in the end what I did was forge my own way of doing that. We always end up being a product of the people we meet. Key people in your life add something to the person you are, especially when you are younger.”

Thorn admits she never had female friends before Morrison. “It wasn’t until I had children that I suddenly found myself in a world where I met loads of women, other mothers going to playgroup and on school runs. I thought, ‘wow, my life is really different now. I can talk about all this stuff and they really get it. It is fun.’

“Female friendships can be a bonding experience. You take strength from each other. You are looking for other women to reinforce you and it vindicates your experience. You think, ‘oh well, I am not going mad then, this has happened to you too.’”

From the book

Do you remember how it began? I do, so clearly: March 31, 1983, backstage at the Lyceum in London.

I was in my dressing room sitting in front of the Hollywood-style bulbs surrounding the mirror – uncomfortably bright lights which showed up the tattered glamour of a faded old theatre, dust motes swirling in the air, a worn-out sofa, a carpet that had seen better days, a window that didn’t open, stale air.

My band the Marine Girls were about to play a gig supporting Orange Juice. Also on the bill were The Go-Betweens.

I was terrified and out of my depth, unused to dressing rooms, sound checks, gigs in London, all of it. In my second year at university, but still a small-town girl at heart, little more than a child. My band was drifting and splitting, our friendships fracturing, and I felt myself coming apart, beginning to wonder who I was, and what I wanted.

Earlier that afternoon I’d been brought close to tears by my first ever encounter with a road crew. Now I was feeling lost and lonely, staring at myself in the mirror. I hated my hair. I hated my outfit. I hated my reflection.

The dressing-room door opened. A breeze. The air changed. Then someone speaking at the top of her voice. Your first words were: “Has anyone here got a lipstick I can borrow?”

I looked up to see blonde hair and a Lurex dress. A tall, angular woman, who seemed to reflect the light, or perhaps you had your own internal source.

You didn’t look like you’d ever been scared to go on stage, or felt judged by your own bandmates, or been browbeaten by a road crew. You looked like confidence ran in your veins. You looked like self-belief in a mini-dress, the equal of anyone.

I can’t remember what I said. I fear that I stared. I tentatively held out a lipstick. Who was this woman?

My Rock’n’Roll Friend by Tracey Thorn is published by Canongate. See Aye Write’s digital programme at ayewrite.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Richard Young/Shutterstock

© Richard Young/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM