It is an iconic scene in a movie full of them but, 25 years ago, as Ewan McGregor races down Princes Street, chased by store detectives and soundtracked by Iggy Pop’s classic Lust For Life, he is hurtling into a new era for Scottish screen.

It is, of course, the opening scene in Trainspotting, a movie that would very soon become a worldwide phenomenon, launching A-list careers of its young stars and director Danny Boyle and changing Scotland’s cultural landscape forever.

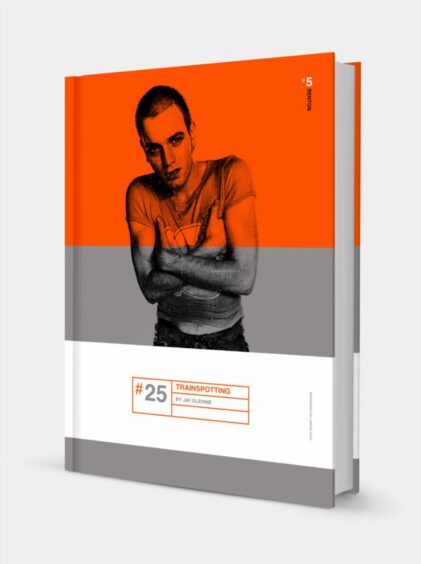

A quarter of a century since its release, film writer Jay Glennie’s new book, #25 Trainspotting, is the definitive history of the movie’s painstaking journey from the pages of Irvine Welsh’s cult novel to the red carpet of the Oscars in Hollywood.

Nowadays, Trainspotting is widely regarded to be one of the most influential British movies of all time. Yet while researching for his book, Glennie found that at first no one knew how to adapt Welsh’s novel, which had no plot to speak of and came drenched in Class A drugs and the vernacular of his native Leith, into a viable feature film. Welsh himself made clear, in memos to the producers, that what they did with his book was entirely up to them.

While questioning the authenticity of some of the dialogue in the initial draft script and making clear he would be disappointed if the movie became a worthy but dull affair about addiction instead of friendship and loyalty, the author, who had a cameo in the film, explicitly excused himself, saying he was more interested in his next project than theirs.

Glennie said: “Irvine told me that from the word go, he was literally inundated with filmmakers wanting to make the film in a very Ken Loach style. But to him, it wasn’t a film about drugs but about this young group of friends.

“When Irvine saw Danny Boyle’s previous film Shallow Grave he thought, ‘Wow, if they can get that spirit into the film, it’s theirs’ and gave them carte blanche. To Irvine, the book he wrote was still alive and was never going to change. He let them make their own film.”

Boyle’s vision for Trainspotting was a cool, modern coming-of-age tale that would inspire a young British audience back to the cinema. His uncompromising vision led to a film that was harrowing and euphoric, shocking and nuanced, and seemed to capture a moment in Britain’s youth culture.

It was released to the acclaim of reviewers and a cacophony of criticism claiming it celebrated drug use. Glennie maintains that was never the production team’s intention. They instead wanted to tell the story of a young group of friends, and explain why they took drugs: “It was key to them that they wanted to show that taking drugs, initially, is fun, otherwise no one would do it. But the downside is that there is a downside, and that’s what they wanted to show, too.

“They didn’t want to glorify drugs, but they wanted to show you that there was a reason that this group of friends took drugs.

“Trainspotting was of its time but it still holds up. Some films are of their time and don’t cross over to the following decades but Trainspotting really has. On paper, it could have been just a lads’ film, but it really transcended and crossed boundaries. They wanted it to be cool for British youth to go to the cinema. It shouldn’t work but it absolutely does.”

Part oral history, part carefully curated collection of previously unseen Trainspotting artefacts, from production memos to on-set photographs to Boyle’s annotated copy of Trainspotting, #25 the book unpicks every thread of an at-times tortuous but ultimately triumphant shoot, and, on Friday, on Twitter, was hailed as the definitive account by Welsh himself. Glennie secured interviews with the author, Boyle, cast members including McGregor, Kelly Macdonald and Robert Carlyle, and was given access to a trove of archive of material, from on-set Polaroids to script pages covered in scribbled notes by cinematographer Brian Tufano.

While Trainspotting now seems like a note-perfect movie, decisions were always shifting and changing during the gruelling seven-week shoot, based in a disused cigarette factory in Glasgow, in 1995. At the end of the film, McGregor’s Renton leaves Ewen Bremner’s Spud £4,000 in a touching goodbye gesture to his old friend. According to Glennie, the scene was almost never filmed.

He said: “The only friction that screenwriter John Hodge and Danny Boyle ever had, was that Danny came to him literally on the day and said ‘Renton is going to leave the money for Spud’. That was guerrilla filmmaking, it literally only took them 20 minutes to film.

“John wasn’t enamoured of the idea, but Danny had seen their characters’ relationship building on screen, and said, ‘This is what we’re going to do’. Now John says that he thinks it’s genius, because we want Spud to have that bit of money. I thought it was a beautiful ending.”

Glennie said that Trainspotting was also responsible for giving the world a genuine, vibrant glimpse at a modern Scotland. Before, Hollywood had often only depicted the country in variations of Brigadoon’s tartan and bagpipes.

He explained: “It felt like before it was very much a Carry On version of Scotland. Boyle wanted to make a heightened-reality version of Trainspotting, but it felt so authentic and real. There was so much great art coming out of Scotland. Someone writing in that broad Scottish vernacular, I had never heard anything like it. In cinema, no one had.”

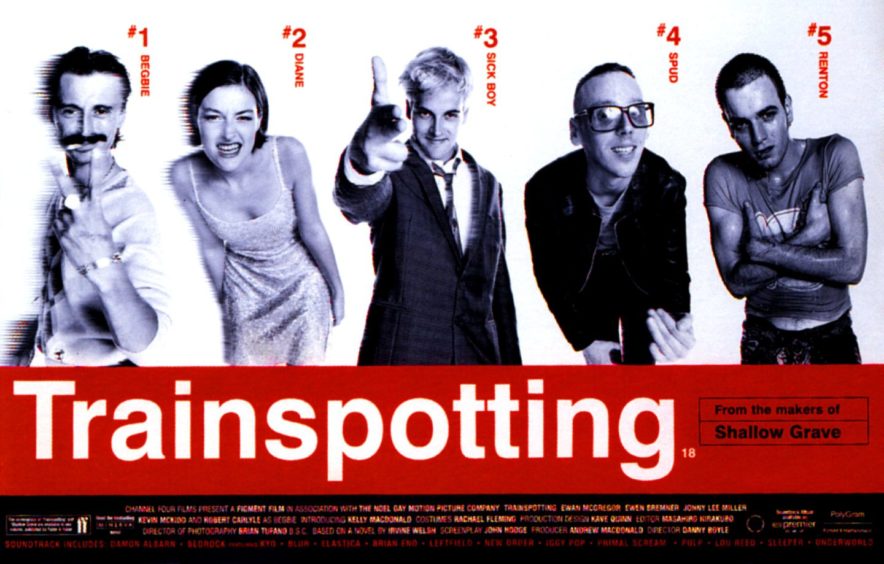

From the cast to the clothes, almost every aspect of the movie blew a gale through the industry. The soundtrack album went multi-platinum in the UK by November 1996, and went on to be voted one of the best movie soundtracks of all time by Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone and Entertainment Weekly. The poster, with the characters photographed separately, was Carlyle’s idea, and became even more iconic.

“It was supposed to be a group shot, but Bobby said no, they’d never be photographed together,” said Glennie. “They wanted to create an image of a band, with separate, fun identities. If you go online now, you’ll see that the poster has been copied and recreated so many times.”

Glennie, who has also written books about The Deer Hunter and Raging Bull, said that getting the talent – including actors who went on to become some of the biggest names in Scottish screen – to talk was easy. Their affection for the film made them more than happy to take a walk down memory lane.

He said: “It was such a huge moment in their lives, and such a pivotal part of their careers. Did they know in 25 years some guy would be pestering them to write a book about it? Probably not! But they all knew they had something special.”

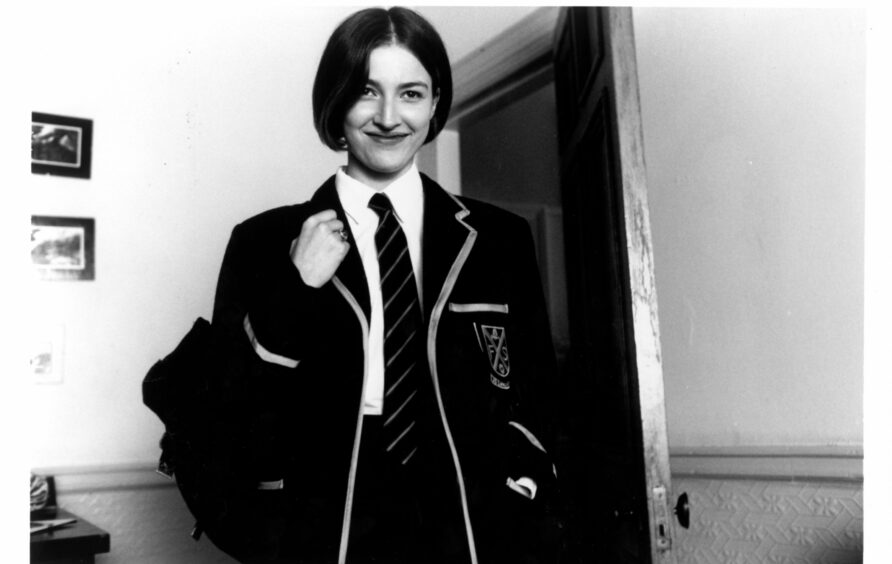

I spotted her as soon as she walked in. It’s odd but can happen like that sometimes. I just remember seeing her and thinking, ‘That’s Diane’

– Director Danny Boyle on Kelly Macdonald’s audition

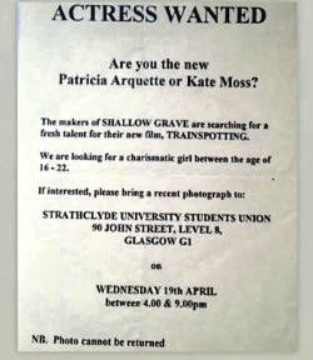

It’s April 1995 and the Trainspotting team are looking to cast a key role – Diane Coulston.

Director Danny Boyle remembers: “We wanted somebody completely new because she had to play this double thing of playing a sophisticated young woman and yet she turns out to be a schoolgirl.”

After passing out flyers in Glasgow advertising a casting call and appealing for the new Patricia Arquette or Kate Moss, a waitress and aspiring actress, Kelly Macdonald, 19, is handed two in the space of an hour.

It feels like fate and will lead to one of Scotland’s most significant screen careers.

Here is an edited extract from Trainspotting: 25th Anniversary by Jay Glennie.

“Kelly, a guy popped this flyer into the record shop and I thought of you.”

Aside from looking nothing like Arquette or Moss, Kelly Macdonald decided to pocket the flyer and read it later. Thanking her friend, she returned to the restaurant to complete her shift. “Kelly, a guy just came in with this flyer and I thought of you.”

Now with two flyers in her pocket, Macdonald felt that she was in receipt of something important. Finishing for the day she fished out the leaflets and read them. Again she reminded herself she was nobody’s idea of Patricia Arquette or Kate Moss and further to that nagging problem was the ever-present issue of her financial situation, which was impeding any sense of excitement. The film was to be based on Irvine Welsh’s novel and each applicant would need a headshot. There was no way she could afford the book and the photograph, and buy food and milk that week.

The solution was to visit the local book shop, where she could read Trainspotting over the course of a few days, which would give a little insight into what the film was about; the toss-up between photographs or bread and milk would have to be resolved.

On the morning of the casting call, Kelly Macdonald took one last look at herself in the mirror. A hairdresser friend had been pestering her to be let loose on her long hair, to do something different and now here she stood, barely recognising herself, with what could only be described as a “bonkers short haircut”. Nervously she took in the rest of her outfit. Her big woolly jumper had holes in it as did her jeans, and did Kate Moss ever wear big black clumpy shoes?

With one last sigh to help quell her nerves, she left her flat, with one more task to perform. Standing in front of the photo booth in Glasgow Central Station she was dithering, the coins danced around the palm of her hand, in synchronicity with her doubts.

“It was a huge decision: either I buy bread and milk or pay for the photographs. I had made the decision that I wanted to move out and here I was wasting money on what on the face of it looked like a lost cause. But I knew that if I put the money into the machine I would have to go to the Trainspotting open audition, because being a good Scot I didn’t want to waste money.”

Photographs in hand, she made her way to Strathclyde University. It wasn’t a building she was familiar with, but somehow she had made it to the correct hall, crammed with attractive young women, seemingly confident in pretty dresses and nice shoes, all with lovely long hair.

Unbeknownst to Macdonald she had already been spotted. She had been right; she was the odd one out and had instantly caught the eye of her future director.

“I spotted her as soon as she walked in,” recalled Danny Boyle. “It’s odd but sometimes it happens and you just know. I remember seeing her and thinking, ‘That’s Diane’.”

Taking a seat in front of the desk at the top end of the hall, she was asked what her name was. The question came from the guy with the glasses and spiky quiff. Forcing herself to look at him, she thought he looked like the singer from the band The Smiths. Handing over her brief résumé and picture she replied: “Kelly Macdonald.”

Looking down the table and nodding at one of his colleagues, the man who had introduced himself as Danny smiled and replied, “Kelly…Macdonald, that’s our producer’s name.”

“What? Your producer’s name is Kelly Macdonald?”

Her response was dry, funny, not rude but with just the right amount of sarcasm and confidence, Danny Boyle recalled restraining himself. A few short questions and Macdonald was back out on the street and making her way home; all that anxiety and worry and for what? But she felt it had gone well; she had a good feeling; had something happened or had she imagined it? Would she ever hear from them again?

It had not been her imagination. In a room of some 900 girls, Danny Boyle felt as though they had found their Diane.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Figment/Noel Gay/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Figment/Noel Gay/Kobal/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM