The sticker in the gift shop was the first hint. “Yinz are nebby,” it read, unlike any American colloquialism I’d heard anywhere on any previous visits to the States.

Nebby? Isn’t that what my dad used to call it when someone was being a bit too sharp?

And what’s this “yinz” patter? Sounds a bit familiar, too, I thought, as I walked through Pittsburgh’s multicultural Strip District, past this yin and that yin.

There was another oddly familiar nugget flashing on a gaudy sign above a downtown corner shop.

“Candies, chips, sodas a’nat.”

A’nat? As in, sweets, crisps, juice a’nat? As in Rab C, Marydoll, Jamesie, Ella a’nat?

I might have been 3,500 miles away on the streets of Pennsylvania’s famous steeltown, but the slang in these streets rang out just like it did at home.

These linguistic Easter eggs, my guide told me as we walked through the streets on a tasting tour of the diverse culinary influences of this neck of town, were just some examples of Pittsburghese, a local dialect which has its roots in the Scottish (and Irish) migration across the Atlantic.

The use of these linguistic markers has given rise to a term traditionally used around here to affectionately describe Pittstburgh’s working class community. They’re known as Yinzers, and whether or not their heritage in the United States leads back to Scotland, the peculiarities of their dialect most definitely do.

The fascinating historical considerations thrown up by the words on the lips of the people here weren’t the only surprise reminders of the place where I’d packed my bags.

On my first day in the city, I took a bike ride along the network of post-industrial waterways, where railways track a river once teaming with heavy industry. Unlike Glasgow – which gained sister city status with Pittsburgh in 2021 – this place hasn’t run out of ideas about how to engage with its river now the industry has died. There are walking and biking trails, baseball stadiums and breweries along the length of the city’s three-river confluence.

There’s even a sculpture of steelworkers in Riverfront Park, which reminded me of the more recent one on the Clyde, the giant Shipbuilders Of Port Glasgow.

Like its Scottish sister city, Pittsburgh has had to forge a new way following a period of de-industrialisation, and art is among its modern-day key identities, nowhere more so than the incredible seven-floor Andy Warhol museum, where the story of one of the city’s most famous sons – and many of his original pieces – draw crowds late into the night.

The Scottish connection continues at the Carnegie Museum of Art, a vast globe-spanning collection and legacy to the Scottish industrial philanthropist’s impact on his adopted country.

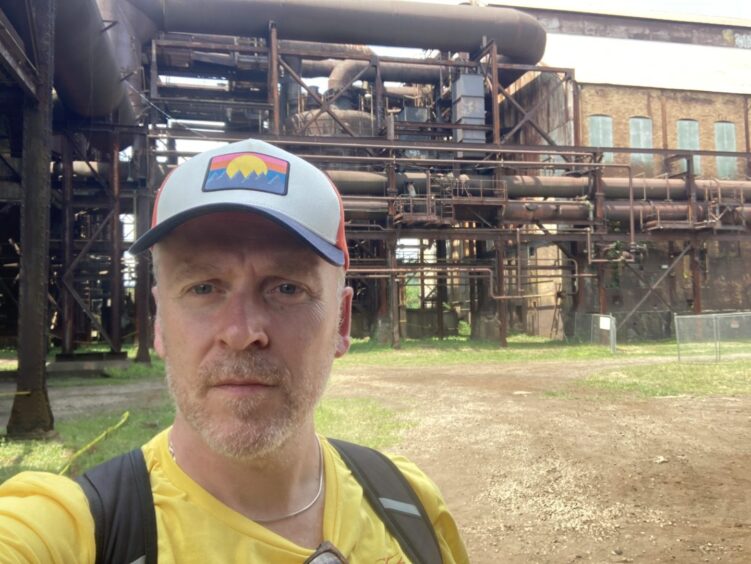

But it was art’s ability to fill a vacuum left by industry which had the most surprising impact on me. The vast Carrie blast furnace, just seven miles outside the city was decommissioned in 1984, and has become a national historical landmark, home to a collection of graffiti and sculpture telling the modern story of the city long after Carnegie.

An (anonymous) resident graffiti artist took us on a tour around this decaying monolith, a giant post-industrial corpse now turned to rust, used as a canvas by the new generation of artists whose spray cans, tags, characters and rules of freestyle urban art were relayed, before he handed over the cans, allowing visitors to have a go. I’d no idea that a visit to a former industrial plant would become such a highlight in a visit to America, nor that I’d leave with a deeper appreciation of the art and community formed by spray paint.

The offbeat theme continued with a visit to Liberty Magic for an hour in the company of whimsical comic Rob Zabrecky, touching on the local history of escapologist Harry Houdini, whose famous upside down straightjacket escape was performed outside a Pittsburgh newspaper office window in 1916.

It’s a part of the city’s history which influenced the city’s famous author, and one of my favourite writers, Michael Chabon. His acclaimed novel, The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, references Houdini’s feats here. Chabon’s debut, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, is a book I first read in 1997, during a summer working and travelling around America. Of course, it was the first book I picked up 27 years later on a browse through Posman Books, a brilliant small-chain indie book store. The familiar, among the unfamiliar, seemingly greeting me at every turn.

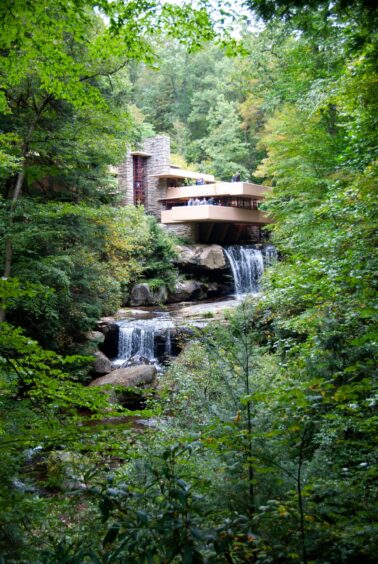

Pittsburgh is the hub city for those coming to the States in pilgrimage to the work of one of America’s most celebrated architects, Frank Lloyd Wright. Within 70 miles of the city lie the awe-inspiring designs of Kentuck Knob and Fallingwater, the latter being as much a part of America’s built iconography as the Chrysler Building and Golden Gate Bridge.

These homes – or monuments to mid-century American architecture – are a must-see on any visit to anywhere even remotely close.

Set among acres of woodland, they represent a rural idyll achievable, of course, to the very few. The fact that these homes were owned by the captains of industry, just a few miles away from a city where thousands broke their backs in the steelworks all their days – says plenty about the inequalities of the fabled American dream.

Still, their elegant beauty is breathtaking, and the architects’ dance with nature draws tourists to see these woodland hideaways by the thousands each year.

It was during a wander through these wooded paths dotted with sculpture on the art trails around Kentuck Knob that I encountered my final, and most surprising, familiar connection.

There in a clearing in the trees, were three pieces of metal, suspended low above a small pond, gently revolving in the wind.

They’re the work of American-born, Helensburgh-raised George Rickey, whose artworks referenced the water he grew up looking at and the heavy industry which sprung along its banks.

The sculpture is known as Three Right Angles. Its companion piece, Three Right Angles Horizontal, was erected in the pond of my local park in Glasgow in 2020.

Finding this piece in these trees, miles away from anywhere, was like bumping into a friend from home. Sister pieces, shared by sister cities, and a reminder now as I pass through Queen’s Park each week, of them Yinz over the Pond.

Factfile

Paul English was hosted by Visit Pittsburgh. Flights with British Airways start from £543 (via London – overnight at Radisson Blu, holidayextras.com). Rooms at The Joinery, Pittsburgh from £117 per night.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Supplied

© Supplied © Shutterstock / Larry Yung

© Shutterstock / Larry Yung