They might – on another channel – be the kind of desirable locations featured on aspirational property shows. Instead, the sleepy countryside village and scattering of cottages around an idyllic beach are hotbeds of nefarious naughtiness and murder most foul.

Last week, fans tuned in to watch tortured island inspector DCI Jimmy Perez close his last murder case – involving just the three terribly violent deaths – on hit BBC drama Shetland. Based on Ann Cleeves’ best-selling novels, the show ranks among the most-watched dramas in the UK, with the latest series averaging just over six million viewers per episode.

Bodies on the northerly archipelago have piled high, with Perez and his small but busy team investigating about 25 murders across seven series. Meanwhile, back in reality, only three homicides have been investigated on the islands in the past 50 years.

It’s no accident that many popular detective series, from Midsomer Murders and Vera to Miss Marple and Hamish Macbeth, play out in small villages and towns with disturbingly high crime rates.

According to Cleeves, who also created TV’s Vera in her Vera Stanhope novels, close-knit communities are a gift to writers looking to drive drama and tension in a murder-mystery.

Speaking from Shetland, she said: “I grew up on traditional British detective stories with the big country house murder or the murder on the island or in an enclosed community where people other people there must have committed the murder. Shetland fits in beautifully for that.

“In a small community, if it’s somebody you know that’s died, obviously, there’s more tension, there’s more suspense, there’s more opportunity to explore relationships during a difficult time. That drives the narrative. A reviewer once called it Village Noir – I quite like that idea.

“I don’t want to write about monsters,” added Cleeves, whose new Vera Stanhope novel, The Rising Tide, isolates the drama, and her beloved detective, on the tiny Holy Island off the Northumbrian coast.

“I want to write about ordinary people and understand why they might commit murder. Not only how they do it, and who does it, but more why they’re provoked to that extreme form of violence.

“Murder isn’t at the heart of the story but rather relationships. In an enclosed community, there’s a sense of having to keep face, to pretend to be someone you’re not. Feelings like guilt, jealousy and envy can eat away at you away and become a motivation.”

Cleeves added that a close-knit setting helped ensure her characters avoided the cliches of the hard-bitten, heavy-drinking city detective. She said: “I didn’t want this sort of miserable, flawed person who had no empathy. I’m a big fan of Georges Simenon’s Inspector Maigret books. Simenon said the role of his detective was not to judge but to understand. My lead characters like Jimmy Perez and Vera Stanhope are ultimately kind at heart, they have compassion, they want to understand and represent the victim but also the witnesses and even the perpetrator.”

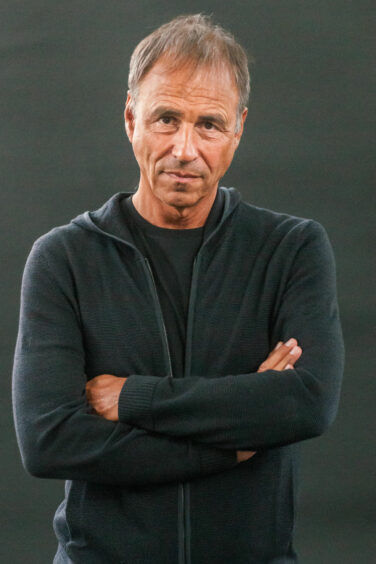

Anthony Horowitz, another best-selling novelist, who adapted the screenplay for Midsomer Murders from the books by Caroline Graham, agrees that small villages are particularly appealing in TV homicides. He said: “A great many murder-mysteries are set in villages because the countryside provides community, an environment where everyone knows one another, so if somebody is a suspect then everybody knows. As everybody is connected, they all become suspects by association.

“I’m always intrigued by the tensions in small communities, the disagreements over minor differences. Emotions can run very high over the smallest things. Somebody planting a tree or knocking down a wall in a village can easily lead to murder. In a city or town you don’t notice these things because life is faster. There are too many people so it becomes more abstract.

“A truth about villages is that what goes on behind net curtains, private conversations, secrets, what’s buried in the garden or hidden in the attic, that becomes everybody’s business. That I think is why so many murders take place in villages.”

No crime show in Britain can rival the iconic Midsomer Murders in terms of both longevity and body count. There have been 395 murders in small villages throughout the fictional county of Midsomer. Fans are clearly happy to suspend belief, as the show has lasted 22 series and broadcast internationally in more than 200 countries and territories.

“It was a perfect formula for ITV. These murder mysteries were very golden age,” said Horowitz. “Although set in the present, they belong to a bygone world of thatched cottages and village greens. The very first episode opens with an elderly lady riding a bicycle along country lanes who discovers something terrible in the woods. The show’s popularity was based on this rose-tinted view of an England that only really exists in fiction. Add to that the bizarre nature of the murders, the quantity of them and the peculiarity of the world, made it very popular.”

He added: “The murders became more peculiar as the show went on; both the quantity and bizarre nature of people killed, crushed by cheese or with a croquet mallet. To me, it made the show slightly less credible, but it didn’t affect its popularity.”

He splits crime dramas into two sub-genres, crime drams and whodunnits or so-called “cosy crime”, where there is comfort in the familiar. Horowitz added: “Familiarity is a large part of it, a sense of comfort viewing, of wanting to revisit a world that audiences know. Midsomer Murder fans want to return to a beautiful place with lots of very beautiful secrets.

“A murder-mystery is not just about murder, it’s about community, relationships and a way to investigate the lives and motivations of people.”

The author, whose many mystery novels include Sherlock Holmes and James Bond thrillers, explained why, in a world where much is uncertain and concerning, we are instinctively drawn to crime dramas.

He said: “The prime appeal is the search for the truth, in a world where truth is often hard to find. We live in a world of 24-hour news, fake news and social media, when nothing is ever certain and conspiracy theories rule.

“But in a crime story, whether a whodunnit or investigative police drama, there’s a quest for the truth. You know that when you get to the final page, or scene, the community will be returned to full health, the murderer would have been discovered, and some kind of peace will be restored. I think that is particularly attractive in the times we live in.”

Cleeves echoed this view. She said: “At the moment, when things are so chaotic, especially since the pandemic, they provide a sort of reassurance because order is restored at the end and there is some kind of justice. I think we were all looking for that with the political chaos we have at the moment.”

Another draw for viewers is attempting to solve the murder-mysteries themselves. Shows like Shetland and Broadchurch have fan sites and Facebook groups where tens of thousands of fans theorise who the murder could be.

Ahead of last week’s thrilling finale, many Shetland fans correctly identified the series’ murderer. Yet Cleeves admitted the murder plot left her guessing. Speaking ahead of the series’ conclusion, she said: “I think some people do like to try to puzzle it out but I don’t usually try to solve the mystery because that cheap thrill of a surprise ending.

“I watch Shetland now because I don’t have a clue what’s going to happen. I don’t get the scripts any more. I watch it wondering what will happen next. The current plot is so complex and confusing I don’t think I could work one out but that’s good because I like the climax coming as a shock.”

An Interesting crime with a beautiful coastal or countryside backdrop. Viewers know the formula and love it

The current golden age of detective crime dramas reflect the format’s enduring appeal, according to Dr Kate Ngai, media and journalism lecturer at Glasgow Caledonian University.

“People’s fascination with crime has been around as long as there’s been crime,” she said.

“When faced with unfeasibly high murder rates in sleepy villages, that willing suspension of belief is easier when viewers are familiar with the situation, the setting and the formula. Our perception of village life is usually idyllic so these crimes can be jarring but, even though murders are being committed, these are safe environments for the viewer. Common tropes such as the familiar small village or town, the underdog detective, a beautiful country or coastal backdrop, and an interesting crime, all create a winning formula.

“It is pure escapism. The murders aren’t too grisly, it’s not too emotionally taxing but a mystery you can solve along with the detective. It’s wrapped up in a nice bow at the end so you can switch off the TV, safe in the knowledge that good has prevailed and justice was served.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© David Hirst

© David Hirst