Restaurateur and chef Nisha Katona is so impressive, any second you manage to snatch with her means you’re guaranteed to learn something.

She is commanding, knows exactly what she’s trying to achieve and there’s a generosity to everything she does – be it the family stories that accompany her recipes, the way she supports the staff in her restaurants, or her charm on TV.

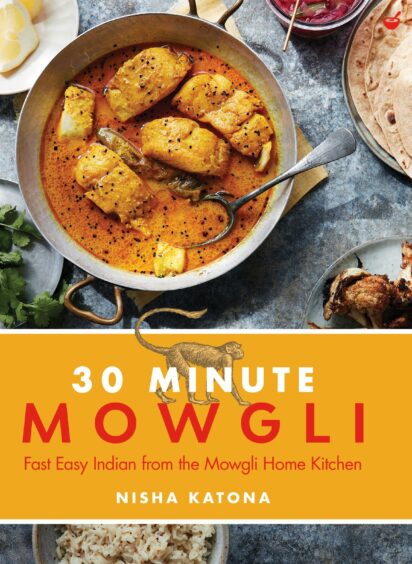

It’s little wonder her cookbook, 30 Minute Mowgli, which was born out of lockdown cooking when ingredients were sparse, centres around quick and easy family meals.

Time is short, understandably. for the mother of two. She was a former child protection barrister for 20 years before opening the first Mowgli restaurant in 2014 and now has numerous branches including in Glasgow and Edinburgh, as well as cookbooks to write, telly to do and her charitable Mowgli Trust to run.

But 30 Minute Mowgli is not just about using up ingredients – there are big flavours at its heart. Katona, who has two daughters with husband Zoltan, says: “The British now want big, instant flavour; it’s not enough just to boil cabbage and serve it with butter, although that’s a beautiful thing as well.

“Sometimes you do want to have a bit of flair. And so it’s really important that we understand the way this nation eats has changed, and is better for it! We look at the way the world does things and we learn from it. And that includes big flavour.”

As such Katona feels a responsibility to share her inherited Bengali, and wider Indian, food knowledge: “We first-generation and second-generation Indians will pass away. What we need to do is make sure the British public who want to cook Indian food can authentically conjure it because we’ve passed the formulas down.

“This way of cooking that I have, it’s thousands of years old…These came from my ancestors through my grandmother, through my great-grandmother, through my mother to me.”

And now to us, via her recipes. The European influences in her cooking are inspired by her Hungarian mother-in-law. She likens the homely, heart-warming Hungarian way of eating to her own Indian upbringing.

Katona says: “We both came from relatively poor backgrounds. You use every part of every ingredient – meat on the bone, you cook with thighs; we cooked with the same sorts of ingredients.”

Katona wastes nothing. In her opinion, broccoli stalks are the tastiest bit, bones stay in, and her grandmother’s best curry was actually a potato peel curry. She also has a particular fondness for cabbages, because they’ll sit for two months in your fridge quite happily.

“We mustn’t be afraid of food that is sitting there quietly, patiently waiting. This whip behind our feet of sell-by dates can be one of the worst things in terms of food wastage,” she says. “Look at it, smell it, has it grown its own ecosystem? If not, peel the outer leaves off and you’re away.”

Katona writes of her ancestral home where instead of “normal toys” she learned to prep fish on her Bengali grandmother’s veranda.

She recalls fish scales going everywhere, all in her hair, and being able to make such a mess because the whole veranda would be washed clean with a bucket of water and left to bake dry in the sun.

“There weren’t acres of coloured plastic when I was growing up, so you would scale fish, gut fish, wash fish; you would mince meat, make kebabs with your hands,” she says. “Before you could speak, you’re mixing dough.”

Then there’s her Indian fish finger sandwich, inspired by long car journeys to McDonald’s in the late ’70s.

“Honestly, we were driving for those fries and for a Filet-O-Fish – we felt as though they had made that specifically for the Indian community, and it’s still got a charm,” she says.

Katona recalls how her mum would zhuzh her bun up with homemade green chilli pickle and slivers of red onion: “My mother still really reveres the Filet-O-Fish.”

That’s some big, instant flavour we can definitely get behind.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe