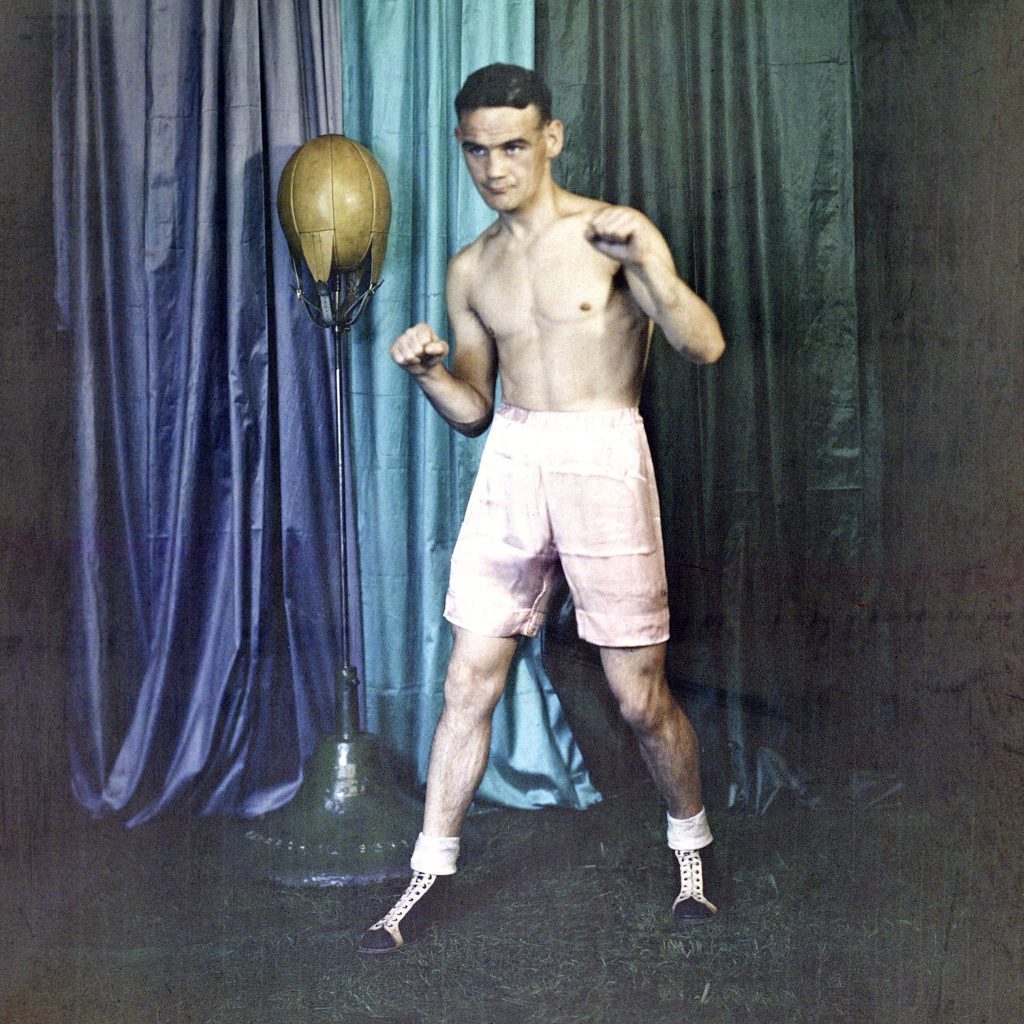

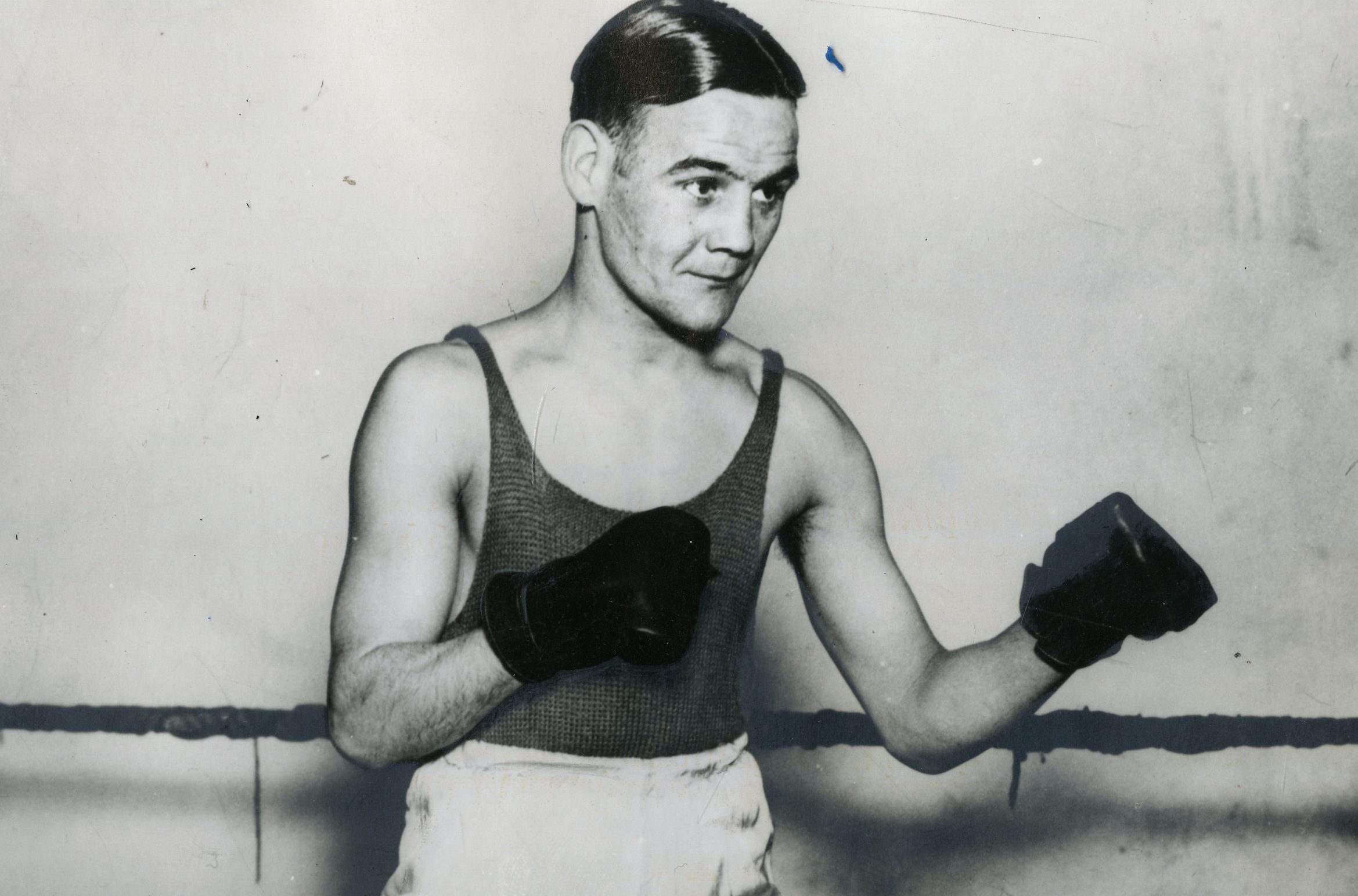

THE story of Benny Lynch’s short life is one of dramatic highs and lows.

A world boxing champion at 22, washed up at 25 and dead at 33, the Glasgow fighter’s shocking demise at the hands of alcoholism means he hasn’t enjoyed the legacy he deserves. More than 70 years after his death, though, that could finally be about to change.

According to the men behind two major works launching this month about the boxer’s life, public support for the people’s champion is slowly winning the day.

Film-maker Shane Tobin, who has produced a documentary about the boxer, and Paul Collins, the writer and director of a play on Benny’s life, believe it’s time he was given the recognition he deserves as one of Scotland’s greatest ever sportsmen.

Shane’s film, Benny, receives its world premiere at the Glasgow Film Festival next week and is narrated by Robert Carlyle.

“It’s probably the most dramatic story in boxing history – the meteoric rise and the equally meteoric descent,” Shane said.

“He was the only show in town, a superstar whose newsreel footage was shown in cinemas in America.”

Meanwhile, Paul’s production, The Lynching: The Last Rounds Of Benny Lynch, launches at the Citizens Theatre, Glasgow, on Tuesday before travelling around the country. It takes place in a boxing ring, featuring a mix of actors and amateur pugilists from local boxing clubs.

“I’m from the Gorbals, like Benny, so I grew up hearing about him,” Paul explained.

“I always wanted to put on the play in the ring – it seemed like its natural home. I feel its a boxing show rather than the theatre.”

The son of Irish immigrants, Benny was a small and sickly child brought up in the tenements of Glasgow’s south side.

He attended a local boxing club and was soon taking on all comers. When renowned trainer Sammy Wilson took Benny under his wing, he turned professional.

He was world flyweight champion by 22 and drawing tens of thousands to his fights.

But his drinking was becoming a problem and he failed to make the weight more than once. When his boxing licence was revoked in 1939 he slipped into freefall.

He tried to dry out in a monastery but his demons were too great and he died from malnutrition-induced respiratory failure in 1946.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe