Dr Samuel Alberti, director of collections at National Museums Scotland, tells Laura Smith the Honest Truth about exploring the curious devices and mighty machines found in science museums, and how preserving past inventions can inspire future innovation.

Why are science museums so important?

Of all cultural attractions, science museums have a unique and broad appeal to multi-generational audiences, with the capacity to inspire the next generation of innovators. They also embed science and technology within the rest of culture.

Tell us about the Large Electron-Positron Collider, pictured on the cover of your book.

It has this Victorian, Jules Verne sort of quality but, when you look at it from another angle, you see the precision engineering of the perfectly cylindrical tube at its core.

In museum terms, it’s quite a large object, 2.5 tonnes of copper, but it’s actually only a tiny part of the collider, predecessor of the famous Large Hadron Collider, which ran for 27 kilometres underneath the Swiss Alps.

Representing science at that sort of scale is a fascinating challenge. We display it next to a video of Edinburgh physicist Professor Victoria Martin, who worked at CERN (the European Organisation for Nuclear Research): a great example of Scotland’s contribution to science.

What other objects are housed in the National Museum of Scotland’s science and technology department?

The science and technology displays are thematic, looking at various groupings including manufacturing, telecommunication, design evolution of various technologies, the production and use of energy and the sort of scientific enquiry and discovery represented by the CERN cavity.

There’s a tremendous range, from the world’s second-oldest steam locomotive and John Boyd Dunlop’s prototype for the pneumatic bicycle to a hydrogen-powered car and a sample of the cable used in the Queensferry Crossing. There are also many significant items from the collection on show at the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian including, perhaps most famously, Concorde.

How much of your collection is in storage?

Despite there being more than 22,000 objects on display, the National Museum of Scotland is very much the tip of the metaphorical iceberg.

The vast majority of the collection is housed at the National Museums Collection Centre in Granton. This is primarily a research facility, although it is accessible on monthly public tours.

As technology and science evolve, is it becoming harder to select objects to display?

Yes! The great profusion of scientific advances across many fields does present a challenge, both the volume of things we could collect and the ways in which we interpret them for visitors. Our curators are constantly asking which objects best reflect current scientific endeavour and its societal impact, but also with a long view as to what will still be of interest to future generations – so we’re currently engaged in collecting the science of climate change.

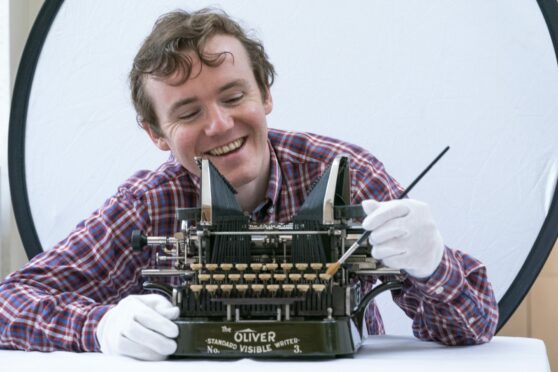

What are some of your favourite “curious devices”?

The “Mignon 3”, on display in The Typewriter Revolution at the National Museum of Scotland. It is very different from modern machines – typists had to pick out one letter at a time with a sharp stylus – but it was popular.

At the Science Museum in London there are two freeze-dried specimens known as “OncoMice’” that were genetically engineered to aid our understanding of cancer. They look like ordinary mice but they represent a huge scientific breakthrough.

Finally, an ugly tractor nicknamed “Bulldog” at the Deutsches Museum in Munich. It was collected to celebrate mechanised agriculture but is more recently used to critique industrialisation in an exhibition about climate change.

Curious Devices And Mighty Machines: Exploring Science Museums, Reaktion Books, £20, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe