On the outskirts of Kharkiv the drone division is preparing to leave for the front.

Two pick-ups trucks, sprayed army green and loaded with kit, wait at a petrol station, and around them five very cheery, very young, volunteer soldiers wolf down hot snacks from paper bags. The sun is shining, their coffee was free, and they’ve got a mission. Morale couldn’t be higher.

The point of today’s mission lies in two nondescript grey wooden boxes in the back of one truck. Two of the boys ride alongside them, hoods up against the biting winter wind, as we head out of the city.

This conflict is the biggest “drone war” we’ve seen, though unmanned aerial vehicles – as they’re properly known – also featured heavily in Nagorno-Karabakh two years ago. Fitted with weapons or cameras, these small and sometimes cheap bits of kit are changing the way war is conducted, and Ukraine, with its advanced tech industry and young population keen to help the army, has led the way in ingenuity.

Suburbs and villages north of Kharkiv lie in ruins. This is where the Russian army reached, in that first phase of the invasion. They dug in here for months and fired, relentlessly, at Saltivka, the vast dormitory district that once housed 400,000 people. The Russians were pushed back – all the way to their own border, 20 miles north – by the Ukrainian army in its blindingly fast September counteroffensive.

We drive over a big intersection, and past blackened shells of houses. “This was the site of the first big battle,” says Masson, a Kharkiv native with a neatly-trimmed beard. That time in late February, when it seemed Kharkiv and even Ukraine might fall, was the hardest. Masson grappled with the options before him. “I never thought I’d take up arms,” he admits, “but the most important question was how I could answer my children in the future, if they asked what I did.”

Before his life changed forever, Masson was a flight attendant – and a pacifist. Now, he says, he feels “only hate” towards Russia. “We thought the Russian army was a monster, unbeatable,” he recalls. “It was David and Goliath. But now we’ve studied them, fought them, we understand it’s all propaganda.”

The flat landscape is a sodden brown, barbed wire stretching across the fields. Boxes are unloaded and prised open. The prototype, once put together, resembles a model plane, with long, white wings.

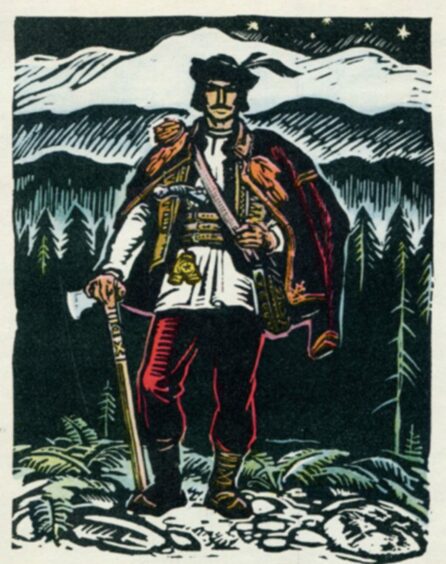

This is a world away from the much-celebrated Bayraktar drones, which are the size of a Cessna and cost millions of pounds each. The makeshift model being assembled in this muddy field is a perfect example of how Ukraine is fighting – yes, with expensive foreign equipment, but also with inventive and cobbled-together bits of kit made by enthusiastic volunteers somewhere in western Ukraine. This particular model is named after Oleksa Dovbush – a 16th-Century outlaw and folk hero.

One of its quirks is the launch method. The Dovbush is fixed to the top of a pick-up and we clamber on behind it. We need to reach about 40 miles per hour to launch, and our “runway” isn’t ideal – the road is scored with tank tracks and bomb damage. But that, it turns out, is not the biggest problem.

Seconds after Masson puts his foot down in the cab, the big white plane flips backwards onto those of us crouched in the back, bits of plastic splintering. We screech to a halt. The drone comes to rest on the road.

The team cluster together to watch the footage of the launch on a smartphone, and determine that the “feet” holding the drone in place were too weak. Clearly frustrated, they note this is a good example of Ukraine’s urgent need for more high-end equipment with which to fight this uneven war.

But a young woman with blonde hair and ammo strapped to her chest, call-sign Mother, is more optimistic. She points to the wing. “These parts are 3D-printed, so if there’s some problem we can change it quickly.” Giving feedback is all part of the process.

Right now, though, Dovbush is going nowhere. The surveillance flight over Russian positions won’t be happening. So it’s on to the next task: bombing.

Nearby another young woman, Vlada, is unpacking a box of ammunition. With sticky tape and pliers she prepares the shells, attaching a clip so they can be carried by the drone. She seems oblivious to the distant and not-so-distant whistles and blasts that occasionally break the stillness here, completely focused on the delicate task.

Suddenly everyone tenses. Masson and Kim jump over a ditch and raise their guns, and all eyes are on the sky. A buzzing noise – like a lawnmower – almost too faint to hear at first, but now distinct overhead. “Is it one of ours?” one of the team asks urgently. “No, definitely not ours,” Mother replies. The drone is so high up it’s impossible to see, let alone take down with an automatic weapon.

“Is it an Orlan?”

The team is silent, listening intently. An Orlan – a Russian plane-shaped UAV that can carry shells – would be very bad news.

Drones make you feel extremely exposed. There’s nowhere to run if it does attack. The high-pitched buzz above us seems slightly absurd; how can what sounds like a lawnmower be so deadly? The team report the drone over the radio and, once the sound has faded away, shrug and get on with the job. The UAV to be launched next flies lower so, to avoid it being spotted, we have to wait for darkness. At this time of year that doesn’t take long: by 5pm the last of the light has faded from the sky, and a bitter cold sets in. Everyone huddles round a laptop, which is balanced on wooden ammo boxes left behind by Russians.

“Thanks to Elon for the Starlink, though not for the tweets,” mutters Kim, who’s been setting up the portable satellite dish. Starlink is vital on the front, but owner Elon Musk’s popularity sank here after he appeared to back the annexation of Ukrainian lands for a peace deal, and complained about the cost of helping Ukraine.

We wait for full darkness, stamping feet and shivering. Then more bad news. Kharkiv, the city we’re returning to tonight, has come under massive missile attack – as have most cities across the country. Both sides have turned on radar, so it’s too risky to send the drone out. The flight can’t go ahead.

It’s a disappointing end to a long, cold day for the small team. As they pack the trucks, illuminated by red lights of headtorches, the temperature is down to zero, with a sharp wind-chill. There’s been much speculation recently that the looming harsh winter will essentially stall the war.

But with no heavy equipment, just small UAVs and laptops, this nimble team is undaunted by any weather. “Yes, winter will be worse for everyone,” Masson admits when I ask. “Harder. Especially in positions – if you sit and don’t move, that’s tough.

“But the war won’t freeze,” he insists. “Quite the opposite.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © EyePress News/Shutterstock

© EyePress News/Shutterstock

© Jen Stout

© Jen Stout © Jen Stout

© Jen Stout