WITH a single step over a weathered, cracked slab of concrete, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un made history by crossing over the world’s most heavily armed border to greet his rival, South Korean president Moon Jae-in.

Mr Kim then invited Moon to cross briefly north with him before they returned to the southern side for talks on North Korea’s nuclear weapons.

Those small steps must be seen in the context of the last year — when the United States, its ally South Korea and the North seemed at times to be on the verge of nuclear war as the North unleashed a torrent of weapons tests.

The moment must also be viewed in light of the long, destructive history of the rival Koreas, who fought one of the 20th century’s bloodiest conflicts and even today occupy a divided peninsula that is still technically in a state of war.

“I feel like I’m firing a flare at the starting line in the moment of (the two Koreas) writing a new history in North-South relations, peace and prosperity,” Mr Kim told Mr Moon as they sat at a table, its precise dimension of 2018 millimetres separating them, to begin their closed-door talks.

Mr Moon responded that there were high expectations that they produce an agreement that will be a “big gift to the entire Korean nation and every peace loving person in the world”.

It was all smiles on Friday as Mr Moon grasped Mr Kim’s hand and led him along an blindingly red carpet into South Korean territory, where school children placed flowers around their necks and an honour guard stood at attention for inspection.

Beyond the surface, however, it is still not clear whether the leaders can make any progress in closed-door talks on the nuclear issue, which has bedevilled US and South Korean officials for decades.

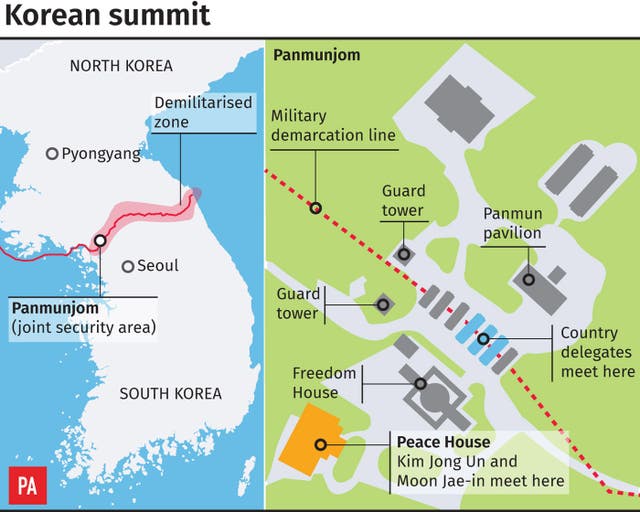

It is the first time one of the ruling Kim leaders has crossed over to the southern side of the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) since the Korean War ended in 1953.

The greeting of the two leaders was planned to the last detail.

Thousands of journalists were kept in a huge conference centre well away from the summit, except for a small group of tightly-controlled pool reporters at the border.

Mr Moon stood near the Koreas’ dividing line, moving forward the moment he glimpsed Mr Kim appearing in front of a building on the northern side.

They shook hands with the border line between them.

Mr Moon then invited Mr Kim to cross into the South; Mr Kim invited Mr Moon into the North, and they then took a ceremonial photo facing the North and then another photo facing the South.

Two fifth-grade students from the Daesongdong Elementary School, the only South Korean school within the DMZ, greeted the leaders and gave them flowers.

Mr Kim and Mr Moon then saluted an honour guard and military band, and Mr Moon introduced Mr Kim to South Korean government officials.

Mr Kim returned the favour with the North Korean officials accompanying him.

They posed for a photo inside the Peace House, where the summit was to take place, in front of a painting of South Korea’s Bukhan Mountain, which towers over the South Korean Blue House presidential mansion.

Nuclear weapons will top the agenda, and Friday’s summit will be the clearest sign yet of whether it is possible to peacefully negotiate those weapons away from a country that has spent decades doggedly building its bombs despite crippling sanctions and near-constant international opprobrium.

Expectations are generally low, given that past so-called breakthroughs on North Korea’s weapons have collapsed amid acrimonious charges of cheating and bad faith.

Sceptics of engagement have long said that the North often turns to interminable rounds of diplomacy meant to ease the pain of sanctions — giving it time to perfect its weapons and win aid for unfulfilled nuclear promises.

Advocates of engagement say the only way to get a deal is to do what the Koreas will try on Friday: Sit down and see what is possible.

Mr Moon, a liberal whose election last year ended a decade of conservative rule in Seoul, will be looking to make some headway on the North’s nuclear programme in advance of a planned summit in several weeks between Mr Kim and US president Donald Trump.

Mr Kim, the third member of his family to rule his nation with absolute power, is eager, both in this meeting and in the Trump talks, to talk about the nearly 30,000 heavily armed US troops stationed in South Korea and the lack of a formal peace treaty ending the Korea War — two factors, the North says, that make nuclear weapons necessary.

North Korea may also be looking to use whatever happens in the talks with Mr Moon to set up the Trump summit, which it may see as a way to legitimise its declared status as a nuclear power.

One possible outcome on Friday, aside from a rise in general goodwill between the countries, could be a proposal for a North Korean freeze of its weapons ahead of later denuclearisation.

Seoul and Washington will be pushing for any freeze to be accompanied by rigorous and unfettered outside inspections of the North’s nuclear facilities, since past deals have crumbled because of North Korea’s unwillingness to open up to snooping foreigners.

South Korea, in announcing Thursday some details of the leaders’ meeting, acknowledged that the most difficult sticking point between the Koreas has been North Korea’s level of denuclearisation commitment.

Mr Kim has reportedly said that he would not need nuclear weapons if his government’s security could be guaranteed and external threats were removed.

Whatever the Koreas announce on Friday, the spectacle of Mr Kim being feted on South Korean soil will be something to behold.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe