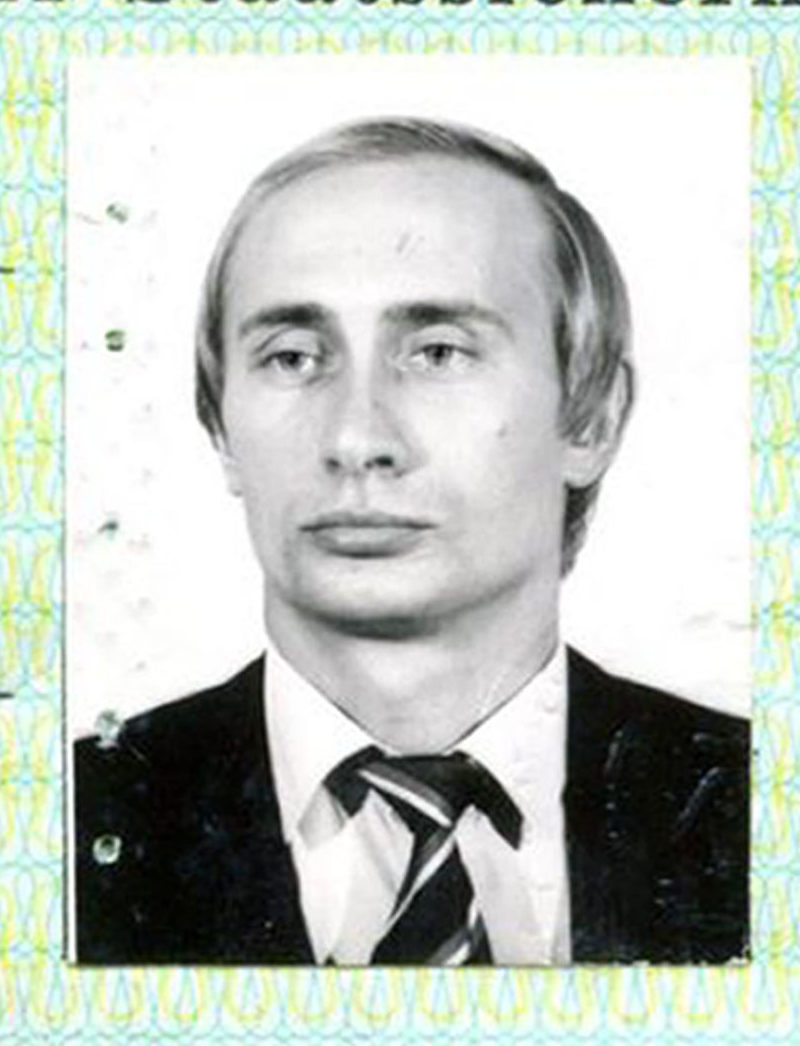

It is 20 years since Vladimir Putin succeeded Boris Yeltsin as Russia’s president and, while he remains popular at home, abroad, his years in power have been marked by conflict, suspicion and international power plays.

Here, three experts assess Putin’s decades in the Kremlin.

THE POPULIST: Dr Elisabeth Schimpfössl, expert on Russian elites

A classical feature of populists, according to scholar Jan-Werner Müller, is to claim the exclusive right to represent “the people” and defend them against both external and internal enemies.

Putin did so when annexing Crimea in 2014 and accusing opponents of being foreign agents conspiring against the nation.

Last month, hundreds of young people repeatedly took to the streets to express their discontent at seeing every single opposition candidate to the Moscow City parliament disqualified.

As previously during the protests of 2010-11 against rigged elections and Putin’s return to presidency in 2012, many protesters were brutally beaten and some face draconian jail sentences of up to seven years. By default, protesters are said to be instigated and paid for by the West.

According to Müller, populist leaders cultivate an image as the saviours of “traditional” conservative, religious values, usually be defending the people from a large influx of immigrants and liberal ideas.

Culture wars of this sort typically go along with a clampdown on civil society organisations, trade unions and environmentalist campaigns.

From the official start of his presidency in 2000 Putin raged against the establishment and the elites. Once in power, Putin picked the most influential 1990s oligarchs, such as Boris Berezkovsky and Vladimir Gusinksy, deprived them of their media holdings and – in the case of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, until his arrest in 2003 the richest Russian – their personal freedom.

Alongside such crusades, many populists run large-scale campaigns against elite corruption.

In Russia, concerns about the effects of endemic corruption were initially articulated by the opposition, first by Alexey Navalny, but soon seized by the Kremlin. This does not hinder many populists to hand over the most lucrative contracts to friends and family.

Elisabeth Schimppfossi, a lecturer in sociology at Ashton University, Birmingham, is author of Rich Russians: From Oligarchs to Bourgeosise

THE STRATEGIST: Dr Matteo Fumagalli, international relations expert

Twenty years ago Russia could have only awaited better times. Throughout the 1990s it had experienced eight years of economic decline. Its economy was in freefall.

The country struggled to control its own territory and had just come out of a second brutal war with Chechnya. It was a largely irrelevant international actor, recovering from the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Russia barely looked like a state.

In the early-2000s President Putin tacitly supported the US-led war on terror and the operations in Afghanistan, as domestically he set out to restore state control. He presided over an energy-fuelled GDP growth of 7% annual average, which allowed salaries and pensions to rise and average Russian families to travel abroad.

Liberal economic reforms, an inflow of foreign investment and the recovery of Russian industrial production sustained growth.

There were, of course, bumps on the way. The Russian economy took a hit in 2009 during the global financial crisis. Putin’s popularity at home plummeted in 2012 when crony capitalism and state repression fuelled societal discontent, sparking widespread protests.

The Kremlin then turned to foreign adventures to stroke popular support at home, striking the chords of Russian nationalism and resentment against the West.

Then came the wrenching of Crimea out of Ukraine in 2014. But sanctions have taken their toll. A decline in foreign investment followed while the rouble has lost 45% of its value since 2014. GDP growth has averaged 0.4% in 2014-19. Real disposable incomes have declined for the sixth year in a row. More than 10% of Russians live in poverty.

The de facto annexation of Crimea, Abkhazia and South Ossetia has come at a considerable price and has only delivered just over two more million Russian citizens and a mere 55,000 extra square miles of new territory. Negligible amounts for a country of 144 million and 6.6m square miles.

But Russia can create havoc. UK relations are at a nadir, as shown by the operation against former Russian spies on British territory and the nonchalant attitude with which Russia operates here.

Yet, if Russian tactics seem to succeed, a longer-term strategy seems nowhere near reality.

Are a dysfunctional Ukraine, the durability of Assad’s regime in Syria and a Trump administration the “best” Russia can aspire to?

Dr Matteo Fumagalli is a senior lecturer in international relations at St Andrews University

THE PUGILIST: Angus Roxburgh, former BBC Moscow correspondent

It was when I worked as a consultant to the Kremlin for a few years, in the earlier part of Vladimir Putin’s rule, that all those bizarre pictures began to appear – bareback on a horse, doing the butterfly stroke in a freezing Siberian river, diving in the Black Sea and tagging Siberian tigers.

Most people assumed it was the idea of the Western PR agency for which I worked. But they were wrong. We were appalled by the pictures.

It was all Putin’s own idea – and said a lot about him. He clearly wanted to project himself as an action man, a strongman who got things done.

But the very fact he allowed the photos to be published betrayed the psychology that has driven his policies for the past 20 years – the bragging of a weakling who longs to be respected.

When Putin came to power in 1999 he vowed to restore Russia’s place in the world.

The country he inherited from Boris Yeltsin was in chaos. Millions had been reduced to poverty by Yeltsin’s reforms, and super-rich oligarchs effectively ran the country. There was certainly freedom of speech, but Moscow’s voice didn’t count on the international stage.

It certainly counts now. But Putin’s plan to make people respect Russia has spectacularly backfired.

In his first years, Putin was determined to be liked. He hobnobbed with President Bush and with Tony Blair, taking them to the opera in his beautiful home city, St Petersburg.

He declared he shared their values and helped out with the “war on terror” in Afghanistan.

But he was fiercely opposed to attacking Iraq and, when the UK and US went ahead in 2003 with what he thought was a disastrous, badly planned war, he fell out with them. He felt Russia’s voice counted for nothing.

When Nato took in new members in Eastern Europe, bringing what Putin saw as a hostile alliance right up to Russia’s borders, he was furious and vowed not to let Nato expand another inch.

In 2008 he attacked Russia’s southern neighbour, Georgia, and in 2014 he attacked Ukraine – both of which had been named as next in line to join Nato. And from 2015 he helped prop up his ally in Syria, Bashir al-Assad, with a ferocious bombing campaign. His message: Russia counts now!

Throughout his 20-year rule, Putin has become increasingly paranoid about his own position. He slowly muzzled almost all the media, and began to rig elections blatantly in his own favour. The parliament is now entirely obedient. And in just the past month riot police in Moscow have violently quelled pro-democracy demonstrations.

His crackdown on human rights, plus the brutality of his campaign in Syria – not to mention the poisonings of his enemies abroad, such as Alexander Litvinenko and Sergei Skripal – have left the Western public appalled by his ruthlessness.

The man who wanted to restore pride in Russia is now feared – but not respected.

Angus Roxburgh is the author of Moscow Calling, Memoirs of a Foreign Correspondent

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Valery Sharifulin/TASS

© Valery Sharifulin/TASS

© Sasha Mordovets/Getty Images

© Sasha Mordovets/Getty Images © Ralf Hirschberger/dpa-Zentralbild/dpa/Alam

© Ralf Hirschberger/dpa-Zentralbild/dpa/Alam