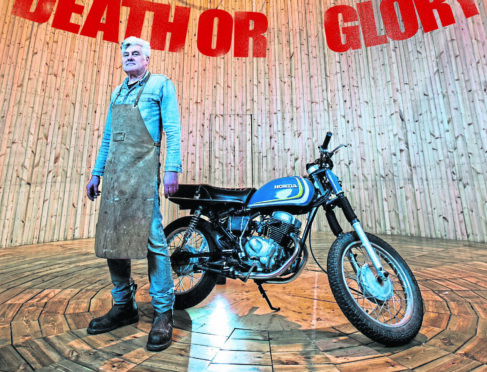

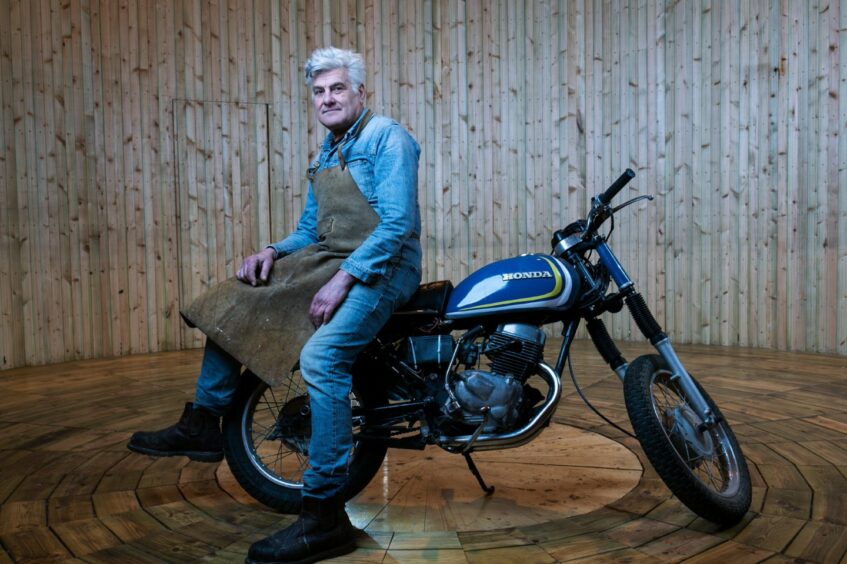

Stephen Skrynka has built a wall of death. The only one in Scotland, he believes.

It has taken more than 13,000 working hours, some three years (or 15 years, depending on how far back you want to trace the idea), the help of a team of unpaid volunteers, a broken foot, a fractured pelvis, a fair portion of humiliation and a few fallouts along the way.

He thinks it has been worth it.

This particular wall of death – a faithful recreation of the traditional fairground attraction that sees motorbike riders defy gravity by speeding around the wall several feet off the ground – can be found in Glasgow, squeezed into the bottom of an old engineering shed, part of the Barclay Curle shipyard near the Clyde, a quick rev or two from Riverside Museum.

This Thursday afternoon in January Skrynka is working on his creation, accompanied by his dog Lottie and volunteer Sarah Martin, better known as a member of indie band Belle and Sebastian.

Skrynka, 61 and the son of a Ukrainian refugee, is a visual artist who has made an artistic career out of challenging himself. Building this wall might be the ultimate example of that. It is a remarkable structure; 28 wooden panels made from recycled pine, containing more than 1,000 joints, standing 18ft tall, and arranged in a circle 29ft in diameter. The Revelator, as Skrynka has named it.

The story behind it might be even more incredible than the wall itself. Certainly filmmaker Maurice O’Brien might argue so. In his new film The Artist And The Wall Of Death – soon to be seen at Glasgow Film Festival – he follows Skrynka’s obsession for years as the artist first tries to learn to ride the wall of death and then becomes driven to build one.

It’s that obsession – not a word Skrynka necessarily accepts – that I’ve come to talk about today.

If you discount Skrynka’s childhood viewing of Elvis Presley in the movie Roustabout, his obsession can be traced back to Devon in 2008 when, on a visit to a fairground museum, he saw riders performing on a wall of death for the first time.

“I don’t think I really knew they still existed until I actually saw them,” Skrynka admits. But as soon as he did he was fascinated.

What drew him to such a dangerous carny thrill?

“The seeming impossibility of it. To me it was much more than a fairground attraction. It’s people risking their lives, it’s a performance. It’s like ballet. It’s very tightly choreographed.

“And I saw it more as an art form than a piece of entertainment, because to me as an artist if art doesn’t engage with life – which also involves engaging with death – then it’s not of that much interest. But also, I fell in love with the space. The potential of the space is what attracted me.”

Initially, it was the notion of riding the wall that he pursued. He approached the National Theatre of Scotland with an idea of touring a wall of death show around Scotland with the Fox family who earn their living from the fairground attraction. As part of the spectacle, Skrynka would attempt to ride the wall himself as an apprentice.

Skrynka had ridden motorbikes before. Not that it helped. “The best wall of death riders are often women who have never ridden a bike. I don’t know why. Riding a motorbike is a hindrance because you’re inheriting a lot of learned behaviours. If you start from scratch you’re actually better off.”

His “apprenticeship” was not the most enjoyable of experiences. “It was terrifying,” Skrynka confirms. “Once the door shut it became a bit of a torture chamber. I was doing all right until I crashed. Once I crashed the first time I realised it is really difficult and it really does hurt.”

He was effectively learning in front of an audience, which didn’t help. “I found the whole process quite humiliating, actually.”

And yet he carried on through the tour, falling over, falling off. You could have stopped, I suggest.

“It nearly got stopped because the National Theatre of Scotland had taken a big risk. Bones were broken…”

His bones? “I broke my foot.”

At which point some people might have said that’s enough. But not Skrynka.

“The crucial thing is, when does an obsession become unhealthy and destructive?” he asks. “And it’s a very, very fine line between destructive and, on the other hand, a way of learning about yourself. It’s a bit of a highwire act.”

Did he cross that line?

“I teetered. I teetered.”

In the film Skrynka more than once acknowledges that projects like this carry a cost. I wonder, I say, if he could add that cost up? Financial, yes. And physical.

“I fractured my pelvis and just general wear and tear. I was probably a bad learner. It probably needn’t have been like that.”

Anything else? “Yeah, I think there’s always an emotional cost. And it’s not always easy to quantify at the time.”

These costs were not his to bear alone though. O’Brien’s film is a fascinating one and by far its most compelling section is when Skrynka travels to Ireland where he meets brothers-in-law Connie Kiernan and Michael Donohoe who, back in 1979, built their own wall of death in County Longford, the inspiration for the 1986 film Eat The Peach.

In 2015 Skrynka staged an exhibition, A Matter Of Life And Death, in Dublin. As part of it he included a news item about Kiernan and Donohoe’s homemade wall of death. He also invited the two men to the exhibition opening. All three talked about the possibility of building another one.

“I sort of said, ‘This is unfinished business for you, unfinished business for me. How about revisiting it?’” Skrynka recalls.

The answer, initially, was a flat no. “That was in the past; it’s dead and buried. We were young. We’re old men now,” Kiernan and Donohoe told Skrynka.

That seemed to be the end of it. “Then I got a phone call maybe three weeks later,” Skrynka adds.

The idea took wing. Donoghue and Kiernan started building a new wall of death in Ireland with Skrynka’s help. It took nine months. Meanwhile, Skrynka got back in touch with the National Theatre of Scotland and started applying to Creative Scotland and to the Irish Arts Council for funding. The wall was built but things got messy. Skrynka and his Irish collaborators were clearly coming from very different worlds, an issue exacerbated when none of the funding applications were successful.

By 2018 things were falling apart. In the film there’s a hugely uncomfortable scene in which Skrynka is confronted by his Irish collaborators. Skrynka is even accused of being a con artist.

“It’s worlds colliding,” Skrynka suggests when I bring the scene up.

He doesn’t accept the accusation? “Of course I don’t. I did not mislead them in any way. I said, ‘Look, we’re after this money. There are a lot of other arts organisations trying to get money from the same source. We might get it, we might not.’ I made no promises because there were no promises that could be made.”

Is his relationship with Donohoe and Kiernan now beyond repair?

“No, I invited Connie over. He seemed keen to come. Whether he does or not, I don’t know,” says Skrynka. “Michael, I don’t know, because I’ve not spoken to him since that scene.”

That could have been an ending but Skrynka is not one of life’s quitters. He returned to Glasgow and as lockdown began in 2020 he started cutting and shaping wood in his back garden.

Eventually, he saw a sign saying, ‘Industrial space to let’ on the side of the Barclay Curle building. That led him to Bradley Mitchell.

“Bradley’s from a showman family. He went to see a wall of death when he was eight and it stayed with him ever since.

“He said, ‘You can use part of the building.’ Without Bradley and his business partner Andrew’s support, there is no way this project could have happened. All these bits of wood would still be sitting in my garden.”

By now Skrynka had been joined by volunteers keen to help; people on furlough, people who were simply intrigued by the project; a fireman, panel beater, oncologist, a pop star and more.

And the end result is this spectacular structure. The Revelator needs a roof – that will be built this year – but otherwise it’s almost finished.

Already it has played host to exhibitions, film screenings and fundraising events for Ukraine. And yes, as the marks on the wall attest, Skrynka has been riding the wall of death again. “109 laps,” he says.

In 2023 he’s not worrying about the costs any more. He can just see the benefits.

“It has created such a huge amount of generosity of spirit, and camaraderie,” says Skrynka. “Just building this structure has involved so many hours of work by so many people; people that I hitherto didn’t know. Why are they doing that? What attracts them to it?

“Partly it’s the wall of death side of it but it’s more about doing something communally, about doing something where you are not in anyone’s pocket.

“We’ve spent more than 13,000 hours in it and there’s not a nail in it, it’s all traditional joints. Everyone has learnt so much about craftsmanship.”

What has he learned?

“It’s a bit like you can’t ride the wall of death from a standing start. I trained as a cabinet maker many, many years ago. High-end cabinet making, but I’ve never really worked as a professional cabinet maker and I think that moment has arrived.

“All those skills I learnt I’ve put to use in different ways. All those skills I’ve learnt are embedded in this structure.

“And I could teach people. And learning that knowledge, that skill just opens people up, increases their self-confidence. If you can tackle this, you can tackle something else.”

So, yes, he says, in the end his magnificent obsession has been worth it.

“I see it as an act of devotion, and as long as you’re devoted to what you do and you do it in the right spirit, it’s worthwhile.”

The Artist And The Wall of Death will screen on March 7 and 8, as part of Glasgow Film Festival. glasgowfilm.org

For more information on The Revelator or to sponsor a plank visit @stephenskrynka on Instagram

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley © Andrew Cawley

© Andrew Cawley