“Mrs Simpson really ought not to go to Balmoral,” growled the veteran politician. “Sacred to the memory of Queen Victoria… if the king really needs to see her, surely she can stay with someone else nearby.”

The king ignored Winston Churchill. Mrs Simpson did go to Balmoral; the trip was a disaster, and scandal was tipped into crisis. By year’s end, the disgraced sovereign had forfeited the monarchy for exile and, though he had many more years to live, he would never set foot in Scotland again.

Eighty-five years on, the abdication continues to fascinate. But this was not, in truth, a romance for the ages. Edward VIII was a dreadful man. He was ill-educated, selfish, and a nightmare to work for; a racist, an open admirer of Hitler. By the autumn of 1936, and in the wake of Balmoral’s horrors, everyone from the prime minister down was desperate to be rid of him.

Nor is Wallis Simpson the grasping vixen of popular imagination. In many ways she was a much more interesting person than her final husband: a woman of considerable presence, sharp wit and mean fashion-sense.

Had she been more discreet, she would have been the perfect mistress and, had he simply been patient, he might just have made her his wife while keeping his crown.

But she was not discreet, and Edward proved reckless. The king never grew into his job – and it fast became obvious that Mrs Simpson was no casual crush: the angular American was his all-consuming obsession.

At first, at least, they were careful. Mrs Simpson did not hang around court or lodge overnight at an official royal residence.

They conducted their affair in the country homes of friends or at Fort Belvedere, the king’s beloved retreat in the grounds of Windsor Great Park, invariably, at first, with the complacent Ernest Simpson in tow.

An edgy establishment and court had not long to wait for the first audacities. Edward continued to firehose his amour with costly jewellery; made over to her a considerable sum of money (and besides bought off her husband).

On at least one occasion he sent a plane to France to bring back assorted luxuries for his lady: items on which not a penny of duty was paid.

In her company, he lost all dignity, dropping to his knees to adjust her skirt, scampering off on incessant errands at her behest. He would read aloud from state papers in front of guests; they were seen strewn by the swimming pool, returned to Whitehall crumpled and ring-marked.

On May 27, 1936, Edward held his first official dinner, in honour of Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and his wife. The guests included the Simpsons, which was bad enough; but the king gave Wallis precedence over every other woman present and, at his express orders, the Simpsons were listed among the guests in the Court Circular the following day.

“Too horrible,” stormed John Reith at the BBC, “and it is serious and sad beyond calculation.” Alec Hardinge, the king’s private secretary – and who cordially loathed him – thought “flaunting” the liaison in this way “almost incredible” but at least, everyone soothed themselves, the King could scarcely marry a woman who had a husband already. And, for the moment, British newspapers breathed not a word.

Then, late in July, the king decided to go on a Mediterranean cruise, chartering the Nahlin, a large and luxurious steam-yacht that John Aird, a long-suffering courtier who would end his career in the service of the Queen, thought “furnished like a Calais whore-shop”.

The guests included Alec and Diana Duff-Cooper, minor aristocrats, some trashy friends of Wallis’s – but not, conspicuously, her husband. They dropped in on Turkey, Vienna, Sicily and Dubrovnik (where vast crowds chanted, in Croatian, “Hurrah for the lovers…”).

Paparazzi secured splendid shots of the pair boating, paddling, bathing, the king frequently stripped to his shorts, as Mrs Simpson laid a proprietorial arm on his. The continental and American press could not print enough of these pictures and, within weeks, furious British exiles were posting clippings home. In our own papers, though, not a snap of the American appeared.

Wallis Simpson was genuinely horrified when the scale of her notoriety became evident, and in mid-September made her first attempt to end the affair, writing Edward to say she wanted to go back to her husband – “I am sure you and I would only create disaster together.”

The king flatly refused to listen, and insisted she now joined him at Balmoral. Alan Lascelles, his assistant private secretary, always insisted Edward had threatened to take his own life if she disobeyed.

Balmoral is traditionally a stately, bucolic break for the royals: wandering hill and glen killing things, entertaining such dignitaries as the prime minister and changing outfits several times a day.

Edward VIII fell on this Aberdeenshire redoubt with the thunderclap of the Jazz Age and guests, for the most part, of matchless vulgarity.

“The riff-raff of two continents,” stormed Osbert Sitwell, “a wise-cracking team of smartish, middle-aged, semi-millionaire Americans…the rootless spawn of New York, Cracow, Antwerp and the Mile End Road…continuous loud laughs bottled in alcohol and always on tap.”

The shade of anti-Semitism is clear enough but Sitwell loathed the incessant gramophone dances, the king’s ridiculous efforts to play the bagpipes, and the fawning manner in which portly Emerald Cunard always addressed him as “Majesty Divine”.

Meanwhile, in parallel vacation at Birkhall, several miles away, Edward’s brother and his wife holidayed rather more sedately – and the Duke and Duchess of York pointedly invited, as their guest, Cosmo Gordon Lang, the son of the manse from Morningside in Edinburgh who was now Archbishop of Canterbury.

Edward loathed Lang, who had long sighed over the prince’s depravities in cosy chats with the late George V, and took this invitation as a calculated dig. Bertie and Elizabeth could jolly well help him wriggle out of a job.

The king had been invited to open the new Aberdeen Royal Infirmary on September 23. But he could not be bothered. He declared he was still in mourning for his late father – though, mysteriously, that logic did not preclude Bertie and Elizabeth from snipping the ribbon instead.

That was bad enough, and great was the Granite City resentment, but it was as nothing to what locals felt when they picked up their evening paper.

“His Majesty in Aberdeen – Surprise Visit In Car To Meet Guests,” thundered the headline of the city’s Evening Express, pointedly alongside a photograph of the Duke and Duchess of York deputising, that same day, for the avowedly grief-stricken monarch.

Worse, the guest was in the singular – Mrs Simpson; Edward, unaccompanied, had personally driven all that way to collect her. And her arrival (sans Ernest) was announced in the Court Circular the following morn.

“Folly,” raged Alec Hardinge. “An act which antagonised at a blow the whole of Scotland.” Within weeks Stanley Baldwin was so alarmed by the weight and fury of mail from a seething public (“the most unfavourable comment throughout Scotland”) that he declared: “Before very long, public opinion would be provoked to an outburst.”

Meanwhile, Mrs Simpson had flapped about Balmoral, as incongruous as a kipper in a thunderstorm. She was given the finest spare bedroom, once that of Victoria herself, with the king occupying the room adjoining – “doubtless,” mews one historian, “for the late-night cups of cocoa that both enjoyed.”

Staff gazed thunderstruck as Mrs Simpson sent their king off to fetch her champagne; seethed in the kitchen when the American ordered, time and again, toasted, triple-decker club sandwiches to her precise instructions; balled their fists as she stalked the building, making such loud comments as “That tartan’s gotta go”; and winced when their sovereign passed the most confidential documents to her. “Darling, what do you think of this?”

“All her judgments were acclaimed by him with ecstatic admiration,” one guest lamented. In fact, though Edward was too lazy ever to notice, more and more sensitive material was now being withheld from his daily red boxes.

Finally, on September 26, with the Duke and Duchess of York due for dinner, Mrs Simpson decided personally to welcome them. As Bertie and Elizabeth entered the dining room, Wallis stepped forward, hand outstretched – the appointed and gracious hostess.

Elizabeth never broke step, refused to engage, seemed not to see her. She simply sailed past the American, with the ringing declaration, “I came to dine with the king.” And, just like that, Mrs Simpson was humiliated. Whether Wallis had been making a calculated powerplay, or simply being pleasant, the couples would never be on good terms again.

Days later, the lovers fled south, like the swallows, oblivious to the graffiti already dotting walls in Aberdeen – “Down with the American Harlot.” “Aberdeen,” Henry ‘Chips’ Channon noted in his diary, “will never forgive him”.

Edward VIII’s calamitous Scottish jaunt was probably the tipping-point that made abdication inevitable even as Mrs Simpson reluctantly sought a divorce. “You can go wherever you want,” hissed the king, “to China, Labrador, or the South Seas. But wherever you go, I shall follow you.”

Far too many people who mattered – Baldwin, the Cabinet Secretary, even his own private secretaries – were now determined he should go: and, indeed, go quickly. Weeks later, at the prime minister’s orders, the king and Mrs Simpson’s phones were tapped around the clock.

The antics at Balmoral, too, had now substantially alienated the king’s own family and, if Bertie did dread ascending the throne in his stead, Elizabeth – as Hugo Vickers has dryly put it – cannot have been entirely blind to the advantages of her new position.

Finally, on December 2 and to public consternation, the press broke silence. Within days Mrs Simpson had fled the country and finally, quite cornered, the king on December 10 signed the Instrument of Abdication.

His long-serving valet, Fredrick Finch – who had known him from his nursery days – flatly refused to join him in exile. Another roared to his face: “Your name’s mud! M! U! D!” And, when the Duke of Windsor finally married his helpless Wallis, in June 1937 – her gown so tightly tailored she could not sit down in it – not one of his relatives attended the wedding.

No one who has made any serious study of this creepy little narcissist can view his downfall as a tragedy. “The abdication of King Edward is the topic of conversation everywhere and I feel quite tired of it,” diarised the Free Church minister of Stornoway. “It is a great blessing and a merciful deliverance.”

Decades later, a friend of mine was chatting with an old Harrisman, a lifelong sailor, who in 1936 had served on the Nahlin. What had the king and his lady been like?

“Well, as for her,” he replied, and in words still more withering in Gaelic, “she was what she was, but he was a rogue and a rascal.”

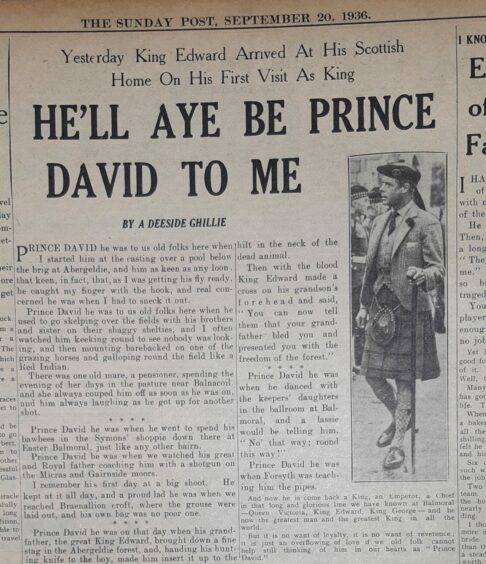

On the return of the king, formerly known as Prince David

On September 20, 1936, the day after King Edward arrived at Balmoral as king for the first time, The Sunday Post ran this article, written by “A Deeside Ghillie” and headlined He’ll Aye Be Prince David to Me.

Prince David he was to us old folks here when I started him at the casting over a pool below the brig at Abergeldie, and him as keen as any loon, that keen, in fact, that, as I was getting his fly ready, he caught my finger with the hook, and real concerned he was when I had to sneck it out.

Prince David he was to us old folks here when he used to go skelping over the fields with his brothers and sister on their shaggy shelties, and I often watched him keeking round to see nobody was looking, and then mounting barebacked on one of the grazing horses and galloping round the field like a Red Indian.

There was one old mare, a pensioner, spending the evening of her days in the pasture near Balnacoil and she always couped him off as soon as he was on and him always laughing as he got up for another shot.

Prince David he was when he went to spend his bawbees in the Symons’ shoppie down there at Easter Balmoral, just like any other bairn.

Prince David he was when we watched his great and royal father coaching him with a shotgun on the Micras and Gairnside moors.

I remember his first day at a big shoot. He kept at it all day, and a proud lad he was when we reached Braenallion croft, where the grouse were laid out, and

his own bag was no poor one.

Prince David he was on that day when his grandfather, the great King Edward, brought down a fine stag in the Abergeldie forest and, handing his hunting knife to the boy, made him insert it up to the hilt in the neck of the dead animal.

Then with the blood King Edward made a cross on his grandson’s forehead and said: “You can now tell them that your grandfather bled you and presented you with the freedom of the forest.”

Prince David he was when he danced with the keepers’ daughters in the ballroom at Balmoral and a lassie would be telling him: “No’ that way; roond this way.”

Prince David he was when Forsyth was teaching him the pipes.

And now he is come back a king, an emperor, a chief in that long and glorious line we have known at Balmoral – Queen Victoria, King Edward, King George – and he now the greatest man and the greatest king inn all the world.

But it is no want of loyalty, it is no want of reverence; it is just an overflowing of love if we old folk cannot help still thinking of him in our hearts as “Prince David.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Everett/Shutterstock

© Everett/Shutterstock © Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock