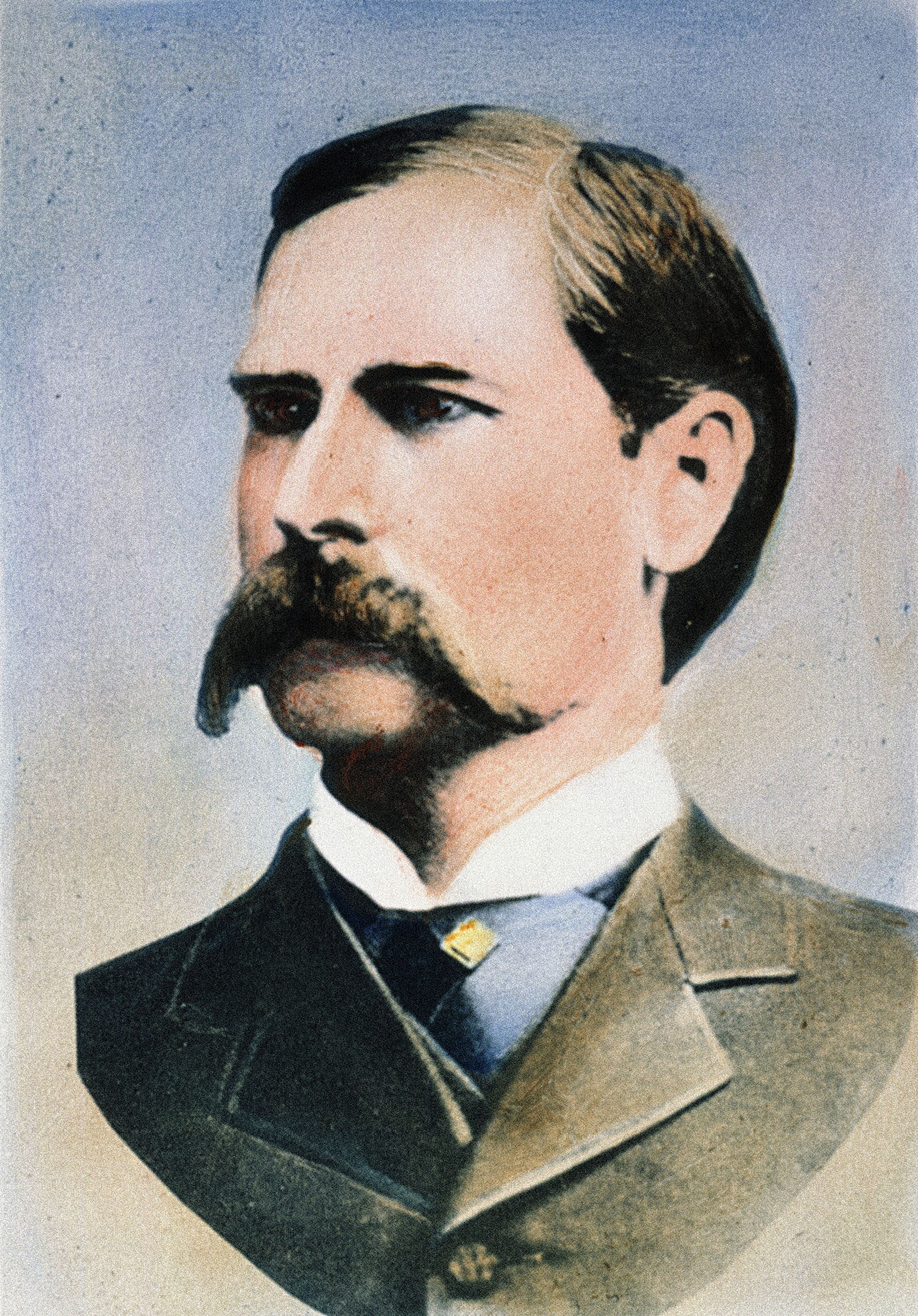

Wyatt Earp – fearless lawman and the Wild West’s deadliest gunman.

Or was he actually a money-hungry convicted brothel owner who’s suspected of helping fix what was then the biggest boxing match in American history?

Like many famous figures from the Old West, Earp’s story has been wildly exaggerated, and his reputation was burnished by a very flattering biography, published two years after his death aged 80 on January 13 1929.

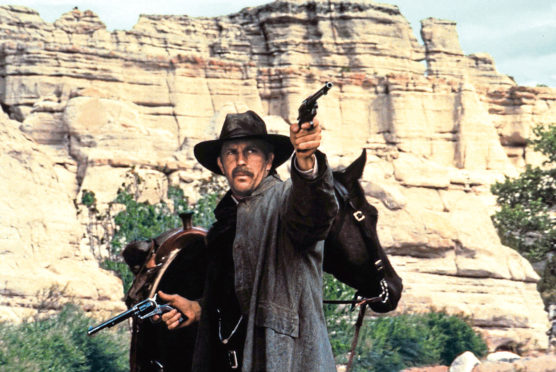

Earp’s modern-day reputation has been further polished by scores of positive portrayals in books and films, in which he’s been portrayed by Hollywood royalty such as Henry Fonda, Burt Lancaster, James Garner, Kurt Russell and Kevin Costner.

Not to mention the hit TV show The Life And Legend Of Wyatt Earp which ran for six years in the late 1950s.

They renamed a Californian town in his honour in the 1930s, and three decades later, Earp received the ultimate accolade when he inspired Jon Pertwee’s character Sheriff Earp in Carry On Cowboy!

What made Earp’s name was taking part in the Gunfight at the OK Corral, undeniably one of the most famous events in the whole history of the Wild West.

What is true is that Earp was a deputy marshal in Tombstone, the town in Cochise County, Arizona, where the gunfight took place.

But his role has been exaggerated as it was actually his brother, Virgil, who was Tombstone’s city marshal and deputy US marshal that day, and had far more experience as a sheriff, constable, marshal and combat soldier.

Conflict had grown with a group of outlaws known as “the cowboys”, and it came to a head on October 26 1881, when Wyatt, Virgil, their younger brother Morgan, and “Doc” Holliday gunned down three of them at the corral.

The lawmen were charged with murder and though they were found not guilty after a trial, a surviving cowboy, Ike Clanton, vowed revenge – he then maimed Virgil and assassinated Morgan.

Earp vowed to kill the murderers himself and he and Holliday formed a federal posse – more of a vendetta ride – killing the three cowboys he held responsible.

Earp was never wounded in any of the gunfights, unlike his compadres, which only added to his mystique after his death.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves, and it has to be said that Earp being appointed as any kind of lawman was somewhat surprising, considering what he got up to in his early years when he moved from one boomtown to another, looking to make a quick buck.

He tried his hand at various trades, being a lifelong gambler, teamster, buffalo hunter, saloon-owner, brothel-keeper, gold miner and boxing referee.

Earp was no stranger to the inside of a jail cell, even escaping from one after being nicked for stealing a horse, and he was arrested three times in one year for “keeping and being found in a house of ill-fame” in Peoria, Illinois.

His third arrest for that saw Earp referred to as an “old offender” and earned him the nickname the “Peoria Bummer”, another name for a loafer or vagrant.

This didn’t stop his common-law wife opening a brothel when they arrived in Wichita, Kansas, in 1874 but the very next year Earp was appointed to the town’s police force and began to develop a solid reputation as a lawman.

Mind you, he was fired after getting into a fist-fight with a political opponent of his boss, following yet another brother, James, to Dodge City, where he became an assistant city marshal, before finally hooking up with Holliday while tracking down an outlaw in Texas, and moving on to Tombstone.

After the feud with the cowboys, Earp moved on again – with yet another common-law wife, one of three, his only wedded wife dying of typhus just before she was due to give birth – joining a gold rush to Eagle City Idaho.

The couple owned mining interests and a saloon but were soon on the move again, leaving to race horses and open another saloon in San Diego.

But his burgeoning reputation was about to be irreparably damaged – during his lifetime at least – when Earp agreed to referee a boxing match between Bob Fitzsimmons and Tom Sharkey in San Francisco.

Billed as the heavyweight championship of the world, Earp was a last-minute choice as ref as he’d officiated at 30-odd matches in his younger days, though not under the Marquess of Queensbury Rules.

Fitzsimmons was favourite and dominated the fight but in the eighth round Sharkey dropped to the canvas clutching his groin, crying “Foul!”.

No one saw the alleged low blow but Earp stopped the fight and awarded it to Sharkey, infuriating the crowd who accused Earp of betting on Sharkey.

Four doctors verified Sharkey had been hit below the belt, but eight years later one admitted he’d been paid $1,000 to fake evidence, and the damage had already been done to Earp’s name anyway.

His reputation in tatters, the Earps moved to Alaska, making the equivalent of $2 million in today’s money from a saloon.

In his final years, Earp spent the winters working various gold claims in California, and the summers in Los Angeles, where he made friends with early Western actors and tried to get his story filmed.

But it took until two years after his death from chronic cystitis for the extremely flattering biography, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, to be published and begin the creation of a what would become a mythical Wild West legend.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Granger/Shutterstock

© Granger/Shutterstock