FROM Bridge Over the River Kwai to the Railway Man, the British World War Two prisoner of war’s plight is one we are all well aware of.

But little is still widely known about the tens of thousands prisoners of war who were kept in this country during the Second World War, and the experiences they had on Scottish shores.

Now, thanks to documents recovered from previous members of Cultybraggan Camp 21 prisoner of war camp near Comrie in Perthshire, new light is being shed on the lives of Nazis and German soldiers incarcerated in Scotland.

Bunte Bühne, a book of pamphlets showing sketches and reviews of theatre performances put on by the most ardent of Nazis at the camp was handed to Comrie Development Trust (CDT) earlier this year by a member of the Deutshe Theatre Comrie’s grandson, and is now on display at Cultybraggan.

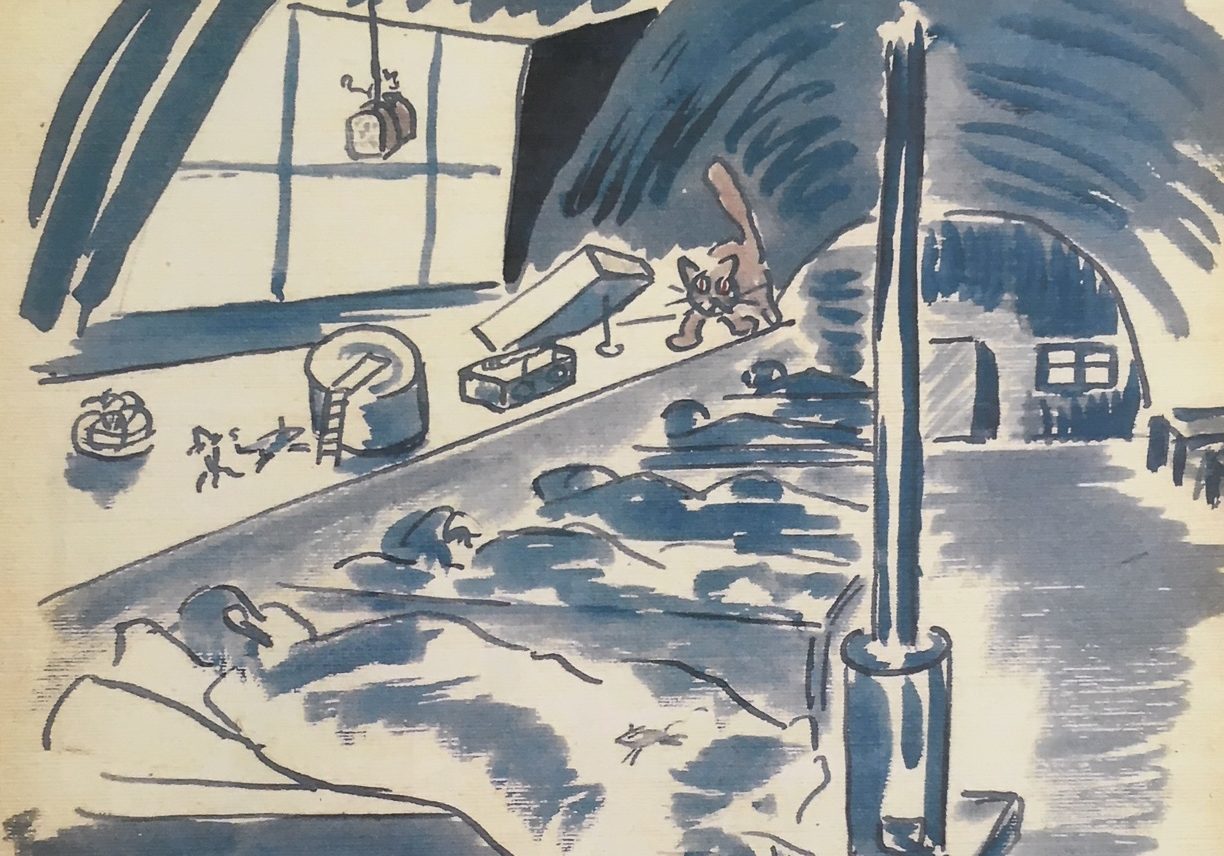

The book joins another entitled “Schottland 1944-” which contains 66 highly detailed drawings of life at Cultybraggan, drawn by a previous German prisoner of war named Peter (his last name is currently undecipherable). This was gifted to CDT by a previous guard at Cultybraggan and is also on display at the camp.

The documents not only depict what life was like at Cultybraggan at the time, but give a humanity to the prisoners of war, says Phil Mestecky, heritage and events manager at CDT. He said: “There’s a real conflict of feeling when you look at these documents, which show an intelligent, comedic and cultured side to the prisoners.

“That’s hard, because you also know that some of them were involved in terrible atrocities.

“However, again, you have to look at the background of these men. Often they were kids, living in poverty. Then the Hitler Youth came in, offered them food, uniforms, activities and structure to their lives. They were basically just brainwashed.”

The humanity observed by Mr Mestecky is one which was also clearly observed by the locals of Comrie when Cultybraggan was at its height, once housing thousands of captured Germans.

Letters have been recovered between the prisoners of war and locals which show established friendships, and stories relayed in a soon-to-be-released documentary on Cultybraggan by Mousehole Films, tell tales of locals smuggling prisoners of war out in school uniforms so they could go to the cinema.

Cultybraggan was one of around 35 prisoner of war camps operating in Scotland during the Second World War, from the Borders to Orkney. Camp 165 Watten in Caithness was home to many “black” Nazis – those considered to be high risk and extremely dangerous.

Read More: Writer unravels mystery of Nazi’s death behind the wire in little known Scottish prisoner of war camp

Cultybraggan was one of two maximum security prisoner of war camps in Britain, and, like Camp 165 Watten, held some of the most hardline and trouble-making Nazis captured during the war.

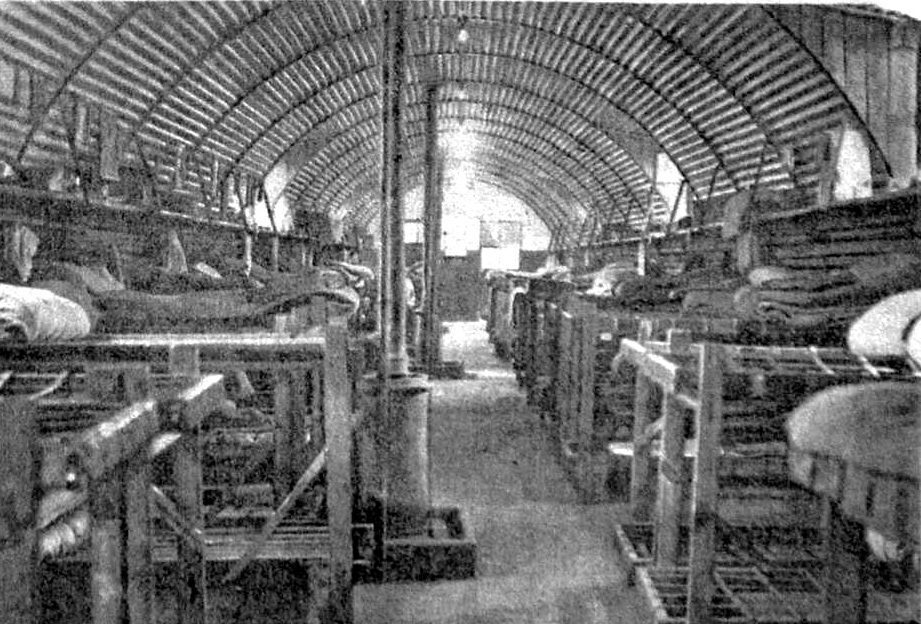

Cultybraggan was set out into four sections of around 100 Nissen huts, A, B, C and D, and each prisoner would be assigned a patch – black, grey or white. Both to identify them, and it is also believed, as an easy shooting target if they tried to escape. A and B (black patches) housed the high-risk, committed Nazis, where C and D (grey and white patches) were home to lower-risk Nazis or German soldiers who were happy to surrender. It was those from C and D who were allowed to go out in to the local community to undertake work like farming or construction.

One story of these low-risk prisoners shows how integrated the prisoners became in the community. Not only did workers trust the POWs in their employ, they were happy to leave their children alone with them at night. One couple allowed the German POW working at their farm to babysit when they were out of town.

“Many of the people in the village had sons away fighting themselves, so I think they wanted to treat these men the way they hoped their children would be treated in the same situation,” said Mr Mestecky.

“It’s clear that the prisoners had a special affinity for the local people. Even the most loyal of Nazis who produced the Bunte Bühne book depict images of jolly Scotsmen. There’s certainly no animosity portrayed.”

Many locals recall the prisoners being brought to Comrie via the old railway line on “special trains,” and how the German’s would sing defiantly as they were marched through the village to the camp.

The POWs went through a de-nazification process at Cultybraggan, part of which showed images of the internal cruelties at Nazi concentration camps across Europe. After this, and as the war drew to a close, many more inmates were allowed to fraternise with locals.

On New Year’s Eve, 1945, a prisoner named Helmut Stenger went to Crieff with a friend for a fish supper. They were greeted by a local policeman who invited them to have a dram at the police station thinking they were Polish. They never told him otherwise.

It wasn’t all rosy however. Although Red Cross records show that the Cultybraggan prisoners were being fed and housed adequately, they would still have been suffering mentally. They had no information about their families, the state of their homeland or when they would be released.

Their lives would have also have become presumably harsher under the rule of the Polish guards, who replaced the British in 1944 said Mr Mestecky.

“The Polish hated the Germans, and drawings in the book of images by Peter depict the Polish soldiers in a much tenser light to the British and Scots depicted beforehand.”

There is also a Red Cross record of a German soldier being shot in the head by a Polish guard for getting too close to the camp perimeter.

When the war ended, and the prisoners eventually managed to find their way back home from Comrie, many of them did not forget the happiness and kindness they had been bestowed in Scotland by the local people.

In 2016, Henrich Steinmeyer, a previous inmate, bequeathed his home and life savings to the elderly residents of Comrie in a remarkable act of gratitude for his treatment there. He was famously called “Uncle Heinz” by the residents he befriended.

Others wrote letters to those they had grown close with during their time in Perthshire, including Wolfgang Ruckert to Mrs Ponsford of Comrie.

He, like so many others at the camp wanted to express his thanks for the kindness they had been bestowed while in Scotland. He wrote in 1948, along with many other wishes of thanks to his Perthshire friend:

“I feel pretty bad because I have not yet written to you…

“I hope you are well and Maryline too. How is the garden and the peas and the beans I was sowing?

“I wanted to thank you so very much for all your kindness you showed me, so that sometimes I could forget that I was a prisoner.”

Today, Cultybraggan is open to the public to explore thanks to the restoration and fundraising work of Comrie Development Trust and the local people of Comrie. Many of the Nissen huts have been renovated into catering businesses with plans to turn a number of buildings into self-catering holiday homes.

Find out more about the CDT and Cultybraggan at www.cultybraggancamp.co.uk

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe