FORGERIES were printer Morton Bisset’s trade but his contribution to Britain winning World War II was the real deal.

Captain Bisset was responsible for setting up a unit to provide forgeries for agents working behind Nazi lines. And it was so top secret, his critical part has never been fully revealed until now.

Author Des Turner was the man who uncovered the unassuming printer’s place in history having already written a book about Aston House – a base for the Special Operations Executive, SOE, dubbed “the Ministry of Ungentle-manly Warfare”.

“There are over 70 of these establishments all across the country, including Scotland,” said Des.

“I’d heard of this one called Briggens, which is near Harlow in Essex and just half an hour away from me.

“It was initially where crack Polish saboteurs finished their training before being parachuted back to help the Resistance. There was a handful of Polish forgers involved in a small way but it was Morton who arrived and set the whole forgery unit up within the training establishment.”

Bishopton-born Morton went to Kelvinside Academy in Glasgow before the family moved to Kent. His dad was a printer and he followed in the family footsteps by undertaking a five-year apprenticeship at the UK’s biggest printing company Waterlow & Sons.

Des said: “It was the best possible training and he became one of the most knowledgeable printers in the country.

“In his early 20s, he was second in charge of their London works with 400 employees, producing maps of Europe in anticipation of the war breaking out.

“He joined the Army in 1939, hoping to be assigned to a Scottish regiment, but his genius was such he was headhunted by SOE who were in touch with Waterlow’s.”

They had contacted the printing firm’s boss, who wrote back saying: “This man is one of the finest types who would do well in any position which demanded intelligence, discretion and tact.”

A bizarre mix-up with another officer called Bisset almost saw him dispatched to become a saboteur in Shaghai. He then resisted initial overtures from Briggens as he was hoping for a more active role before being persuaded that his printing experience would be invaluable.

The set-up at Briggens was rudimental and the equipment basic until Morton’s arrival.

He used his contacts to get a proper lithographic printing machine and built the unit up from three men to being 50-strong.

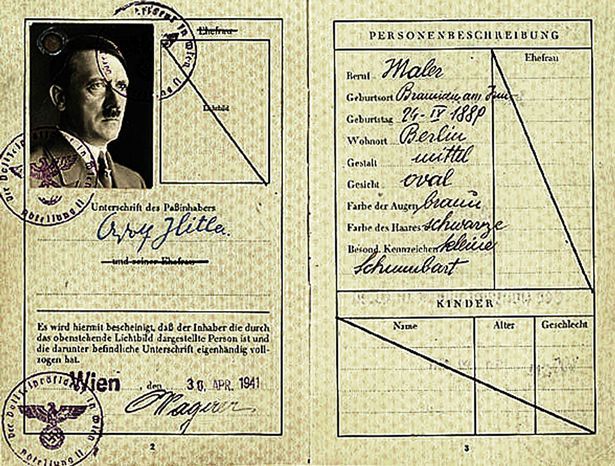

“The section was initially producing documentation just for Poles but then SOE decided it could do everything,” said Des. “It became their central forgery department, coming up with identity papers and all the other things required for British agents and everyone else going behind enemy lines.”

The crack team went on to create more than 275,000 such documents to help the underground fighters.

The key to it all was getting an original to work from and that was a highly dangerous, high-speed business.

Passports, identity cards, driving licences, ration books and other essential paperwork would be stolen or borrowed on the continent and then rushed to Briggens.

“They were brought by motor torpedo boat, submarine or aircraft,” explained Des. “They had to be copied just as fast as possible and then got straight back across the Channel. If possible that had to happen on the same day before it was noticed that they were missing.

“If you’d handed over your identity card and didn’t have it when you were asked you could be in big trouble.”

Money was no expense when it came to getting things right.

To avoid any suspicion, even if only one special Polish identity card was required, they would think nothing of having a supplier make 10 tons of the proper paper.

The talk was that when the Americans entered the war, they initially weren’t as painstaking in sourcing authentic paper and they tragically lost some of their operators.

One top secret letter from Whitehall to Morton in January 1942 highlighted the importance of the very best forgeries.

It told of an agent arrested on crossing a border. “During the search the man was carrying documents which had been produced by you.

“These documents were subjected to the normal scrutiny of a frontier post and were accepted as valid.

“The agent in question was imprisoned for the nominal few days for illegally crossing the frontier, and subsequently released.

“Up to the present we have had no information of arrest or failure of any of our agents due to the documents which they carry not being authentic. This is a matter for self-congratulation.”

The pressure to ensure that every single document was perfect lest it left an agent facing a firing squad was a heavy burden. And Morton never let up in his quest for absolute perfection.

“At one stage they had to turn out ration stamps that had perforated edges,” said Des.

“As they didn’t have a machine to hand, Morton worked all night with his deputy to do it by hand. They made every single perforation, perfectly spaced, with a blunt dart and a light hammer.

“They were aware that papers often had to be ready for when there was a full moon as that’s when agents were flown back to Europe, so speed was the key.”

Des has spent years in detailed research, uncovering letters and other documentation about the unit as well as rare examples of the unit’s work.

But crucially he also met and spoke at length with Morton, who happily shared his own archive of material before his death a few years ago.

“He was a wonderful character, I loved the man,” said Des. “It was clear that although he spent a lot of his life in England, his heart was in Scotland.

“He was very much one of those unsung heroes. I got the feeling when I met him and he handed over the things he had, that he saw me as the last chance for the story of this unit to be told.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe