If you’re looking for somewhere interesting to visit in Glasgow, the city has no shortage of fancy big galleries and museums.

However, if you want the one that has just beaten them all in a top awards ceremony, you need to find an unassuming little backstreet.

You’ll find the Glasgow Police Museum at Bell Street, close to the Trongate, a small place with former policemen ready to show you round and bowl you over with their knowledge and enthusiasm.

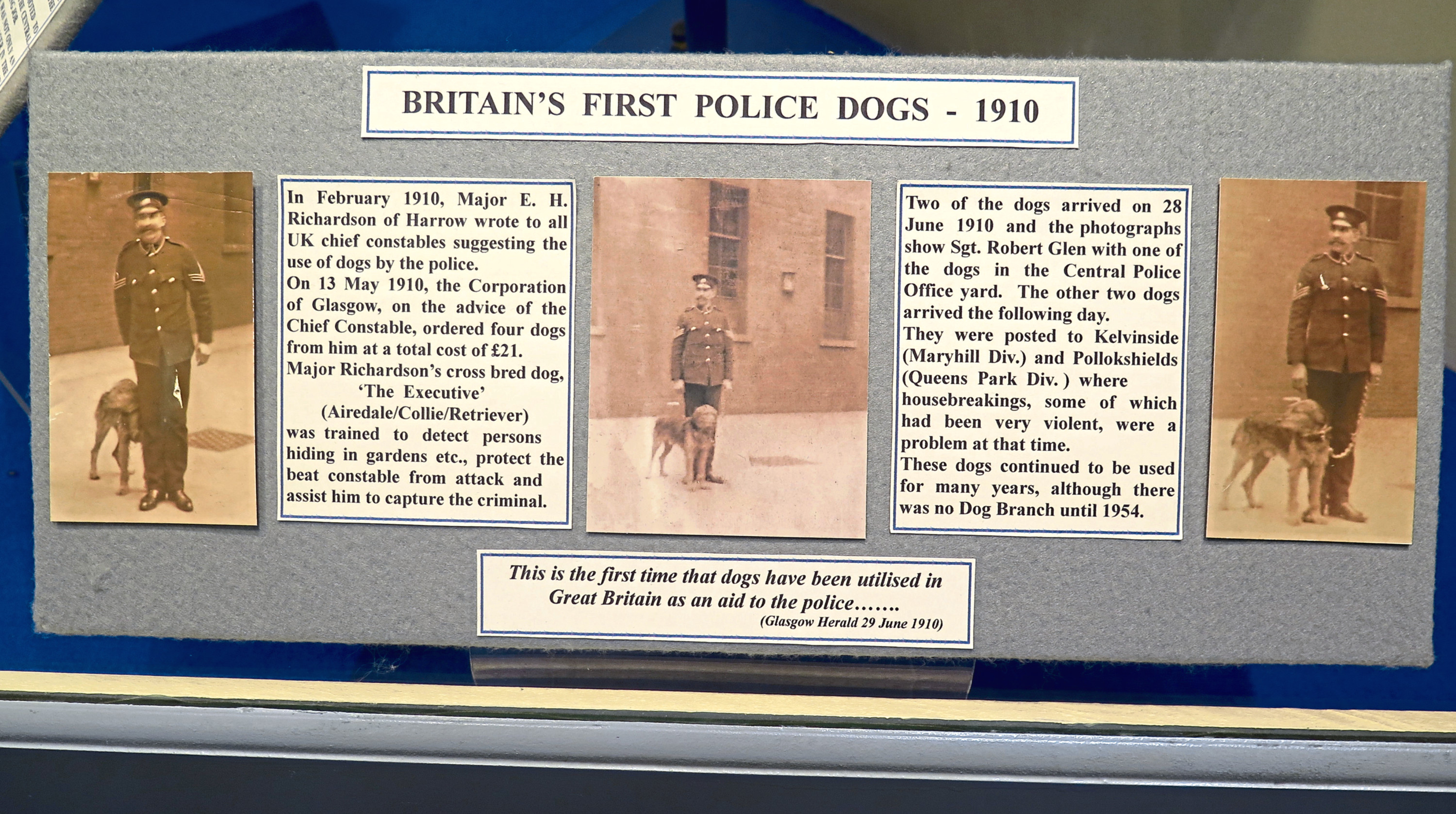

The first thing that surprised a Glaswegian like myself was that my city had Britain’s first police force, was the first to use dogs, and has the largest collection of international police uniforms in Europe.

Every day, visitors come from far and wide, from Taiwan to Tallahassee, Timbuktu to Tottenham, and they all leave with a new appreciation of the police force and the amazing work they do.

“We started in offices at the old police station at St Andrews Square in 2000,” says curator and chairman Alastair Dinsmore, a former inspector.

“It took us almost two years to build the museum, but that building was closed in 2008, and we moved to where we are now, reopening the following year.

“We have uniforms from all over the world because that is a hobby of mine. A lot of the badges, too, are from my own collection and are on loan to the museum.

“This is a hobby that is quite common to policemen around the world, we do swaps, and when we go on holiday we do trades with the local policemen, patches and things like that.

“The thing that really sparked off the Glasgow police in 1779 was the American Revolution. Glasgow had a virtual monopoly of the tobacco trade, bringing Virginia tobacco to Europe.

“It was processed here, and when that was cut off, the city went into an economic decline. This brought crime and poverty, and the city magistrates needed somebody to help them.

“So the police force was formed. It was an on-off thing for a number of years, because nobody would pay for it. In 1800, we got the Glasgow Police Act that allowed the city fathers to tax the people.

“That was the start of the ‘Rates’ and it lasted for about 180 years, so it must have been a reasonable system.”

As you can see, there is a fascinating story behind how Glasgow was first to have police, and these days the museum receives a large number of visitors from every corner of the world – except one.

“We’re getting between 9,000 and 10,000 visitors a year and we are highly rated on TripAdvisor, Google, all these kinds of things,” says Alastair.

“We get people from every continent except Antarctica. The door opens and somebody comes in from Brazil, somebody else from Singapore. It’s amazing who’s visiting Glasgow.

“Universities help, too. Parents of overseas students come for a holiday and to see where their children are staying, and visit the museum while they are here.

“We also get policemen from all over the world. A couple of years ago, we had a policeman from Kazakhstan who was doing a course in England and thought he would come up. Because we didn’t have his uniform on display, he went back home and sent us one.

“We get everybody here, a good cross-section. The one category we’d like to attract more is the Glaswegian, because people here tend not to look for what’s on.

“They tend to think they know what’s on, and it’s only when they have visitors from abroad that they start to look at the different things that are on here. We are trying to get the message out to the greater Glasgow area.”

From revolvers used in notorious crimes to fingerprints of murderers, antique batons, a huge range of medals and gadgets used over the years for communication, the museum is chock-a-block with fascinating paraphernalia.

A visitors’ favourite is the vast array of weird and wonderful international police uniforms.

Some of the head wear wouldn’t look out of place among Napoleon Bonaparte’s cavalry, the Fijian sulu wraparound skirt is another stand-out, and of course the famed red Mounties uniform is a real classic, too.

One thing foreign visitors wonder about is something British police always get asked – how on earth do they manage to do their jobs without being armed like so many overseas forces?

“There are quite a few who do ask about that,” says Alastair. “We tell them that while the street police officer doesn’t have a gun, there are firearms available and armed response vehicles.

“It seems to work, even though there have been a number of fatalities over the years. It seems there’s going to be no move towards arming our police.”

The museum is suitable for kids, too.

“We have a LEGO manhunt for the younger ones and a museum quiz for the older ones,” Alastair points out. “They get a Junior Detective Award certificate on completion. We are also a learning destination for the Children’s University.”

As Alastair says, Glasgow’s force possibly led the way because people were open to trying new things back in those early days.

“After the Enlightenment, people had ideas and tried them,” he says. “So when magistrates wanted to start a police force, it happened. Then when somebody offered them dogs, that sounded like a good idea, too, as they were having problems with burglars in the West End.

“They got four dogs. It was a matter of seeing a good idea and going with it, rather than sitting round a committee and pulling ideas to bits.

“We have certainly led the way, and in forensics as well. The first person to be convicted because of a toe print was the work of a Glasgow detective.

“We get forensics students from all over, particularly from America and Canada, and we show them round and tell them all the things our forensics people did.”

One small item that intrigued me was a tipstaff, something I’d never heard of.

“Policemen in those days carried their baton out, in their hands, because having the King or Queen on it was a bit of symbolism to say, ‘This is where I get my authority.’

“If you were a plain clothes policeman, that would give the game away, obviously, so they had a tipstaff, a miniature baton with the crown on it. Like Americans have a badge they can show.

“Remember that a lot of people couldn’t read or write then. If you showed them a warrant card, they wouldn’t know what it said on it.”

If you visit this fantastic, award-winning museum, you’ll learn plenty and never look at Glasgow or its policemen and women the same way again.

You can learn more about the admission-free museum – it survives by your donations – at policemuseum.org.uk, calling 0141 5521818, or dropping a line to curator@policemuseum.org.uk

The museum is open every day of the week until 4.30pm up to October 31. Between November 1 and March 31, it is open Tuesdays and Sundays.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe