An unstoppable surge in the number of wild boars has been predicted as Scottish farmers voice deepening concerns at their environmental and economic impact.

There are several large populations of the huge swine but experts say they are now present across Scotland and failure to curb numbers means they could grow dramatically.

One estimate suggests the numbers have risen tenfold in 15 years with between 3,000 and 5,000 boar currently wild in Scotland. Ministers are being urged to take action to prevent the numbers running out of control.

Steven MacKenzie, a stalker on the Aberchalder & Glengarry Estate in the Great Glen, shoots 40 wild boar per year and believes there could be 700 of the animals in the surrounding countryside. One male boar he shot was 30 stone, and almost 8ft from rump to snout.

MacKenzie has witnessed large boar killing sheep on the estate’s farmland. “We have had a number of incidences of not just lambs but full-grown sheep being knocked down by large boar,” he said.

“Once they’ve got them on their backs they’ll use their tusks to open their stomach up and get at the soft content. We have actually seen this happening. It’s horrific.”

Christopher Ellice, owner of the 32,000-acre estate, said: “One of these days a tourist will come across one that will consider itself trapped and then they could be extremely serious. We could have a death.”

An unpublished report from seven years ago but obtained by The Sunday Post told ministers there were three options: to do nothing; cull all boars; or control numbers. NatureScot’s investigation in 2015 warned taking no action carried “the risk of populations growing in parallel with environmental and economic impact,” and pointed to Texas to illustrate what could happen if nothing was done. The state now has around 2.5 million “feral hogs”, which the report’s authors say are beyond control. No policy to control the boar population in Scotland has been introduced.

Farmers say the animals kill lambs to eat, and plough up fields rooting for food. The wild animals could spread disease affecting valuable domestic pig herds. Boar on roads pose a risk to traffic, and there are fears hikers could be in danger if they confront them. Tusks can be up to five inches long.

Although boar can improve biodiversity in some woodlands, they can damage populations of ground-nesting birds and deplete food supplies for other wild animals. They eat woodland plants such as bluebells.

Native boar are extinct, and Scotland’s population is descended from escaped animals imported to farms and estates for hunting or meat. Some were crossed with domestic pigs to produce bigger litters – piglets are nicknamed humbugs because of their stripes – increasing their spread.

Two major boar populations, each estimated to be of several hundred, live around the Great Glen in the Highlands, and in Dumfries & Galloway but Andy Riches, a wildlife recorder for the Mammal Society conservation charity, says boar are now all over Scotland, including groups in Tayside and Speyside.

After examining records for the whole of Scotland, he believes numbers have increased in the past 15 years from around 400 to between 3,000 and 5,000, and they are still rising, despite shooting by stalkers and farmers.

Lea MacNally, a stalker and farmer from Glengarry who says he has had many lambs killed and eaten by wild boar, is angry at the Scottish Government’s inaction. “Nobody is giving us compensation. It’s a serious problem but they seem to have just ignored it,” he said.

“They’re never going to eradicate them now, it’s gone too far. They are in the village in Invergarry. One guy had his garden trashed, got it fixed, and six months later they came back and did it again.”

Mike Toms, a crofter and deer manager from Glen Moriston, has studied wild boar and has given talks to Police Scotland and the Ministry of Defence representatives about dealing with the animals. He has shot numerous boar, including those which invade his fields and ruin the grazing. One was a 22-stone male. Toms said the lack of action from the government was “at best” disappointing, adding: “A more serious view might say it is irresponsible and embarrassing.

“An impartial bystander might be forgiven for suspecting that the whole circumstances are a perfect conspiracy to reintroduce and spread boar in the UK without legislation or evaluation of the threats and likely impacts.”

Problems with boar are not confined to the Great Glen. Willie Graham runs Auchengray Farm, near New Abbey, south of Dumfries. He believes there are “thousands” of boar in a swathe of woodland, hills and rough grazing south and west of the town.

His fields and those of four other farmers are regularly torn up by them, costing time and money to relay. “If you just leave where they have dug, you get nothing but weeds,” he said. “They need to be controlled. They are getting worse every year.”

Robin Traquair, National Farmers Union Scotland vice-president and Midlothian pig farmer, said: “These animals will multiply rapidly and I would say the government needs to step up to the plate and be clear with the public what they’re going to do so we can plan ahead. We need to find out how many animals are there and work out if we want to eradicate or tolerate them.”

If foot and mouth disease or African swine fever, which has devastated pig farms in China and spread into western Europe, crop up here, wild boar could hasten their spread, said Traquair. They could also spread mange and parasites. He added: “In the north-east we have successful outdoor pig-farming enterprises, and wild boar would not work well together with that. Control is needed to avoid these farms going out of business.”

The conservation charity Trees For Life also called for a government strategy. It owns the Dundreggan Estate in Glen Moriston, an area affected by boar.

Charity chief executive Steve Micklewright said the boar can bring ecological benefits by rooting in woodland soil, opening it up to seedlings and helping biodiversity, but in farmland “they can have unacceptable negative impacts which may need managing”.

“We need a well-considered national management strategy that works for everyone by addressing both the benefits and challenges brought by wild boar, together with more research into their distribution, spread and impacts,” he said. “And the Scottish Government should recognise wild boar as a native species within their natural range.”

Civil servants are using the report to develop an overall strategy for feral pigs in Scotland, said the Scottish Government, adding: “While estimates suggest the number of boar wild in Scotland is currently low, and populations are predominantly feral pigs, we are aware that their numbers may be increasing.”

Best practice guidance on managing feral pig populations has been developed and it has been used at a local level. The Scottish Government added: “We encourage all pig keepers to ensure they have good biosecurity measures in place to prevent contact with feral pigs.

“Working with NatureScot and other stakeholders, we will continue to consider whether any further action is required.”

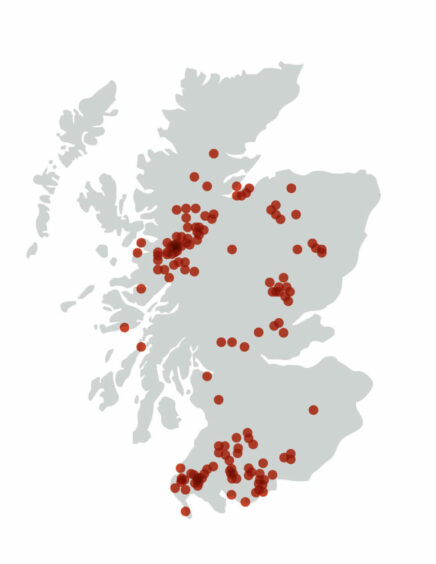

The whole hog: Boars have been spotted all over the country

There are at least three confirmed major populations of boar in Scotland but a map of reported sightings suggests they may be living in the wild across the country.

A map of accepted sightings over the last 20 years, compiled by the National Biodiversity Network, shows boars from the Borders to the Highlands.

They were hunted to extinction in Britain around 300 years ago but were later imported for meat and some escaped from farms and private collections to establish populations in the wild.

Usually nocturnal, the boar eat plants and meat and have been blamed for killing lambs and even sheep but would rarely attack humans. Where they are crossed with domesticated animals they are referred to as “feral pigs”.

There are still some wild boar farms in operation. Some sporting estates offer wild boar stalking to guests, and many boar which invade farmland are shot by farmers and stalkers but numbers are thought to be still rising.

Wild boar were illegally released in the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire in 1999. In one year, between 2013 and 2014, numbers increased from 535 to 819, despite 130 being shot. They damage verges, gardens, play areas, parks, golf courses and private gardens. They attack dogs, and riders have been thrown off horses scared by feral pigs.

Introduced wild boar, pig/boar hybrids and “feral hogs” are now common around the world. North America never had native boar but Texas now has around 2.5 million feral hogs, and reports from the state say they erode the soil and muddy streams, damaging aquatic life.

They also disrupt native vegetation and make it easier for invasive plants to take hold. The hogs eat livestock food, and occasionally young livestock, plus deer, quail and the eggs of endangered sea turtles. In urban areas they occupy parks and sports fields, invading gardens and attacking pets.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Shutterstock / Budimir Jevtic

© Shutterstock / Budimir Jevtic