AS he looks down his garden, Graham Robb could not imagine a more tranquil scene.

The river at the bottom, bubbling gently, marks the border, the dividing line between England and Scotland and, in the cold, bright calm of a spring day there is no hint of the tumult that has gone before.

But when acclaimed author Graham made the move north to be closer to his Scots family, he had no idea of the blood-soaked history of the land where he settled.

His Cumbrian farmhouse is right in the heart of a territory that was, at the height of its notoriety, the most dangerous in Britain.

But it’s a past, and indeed an area, that few know much about. Now Graham hopes to put that right with a new book called The Debatable Land.

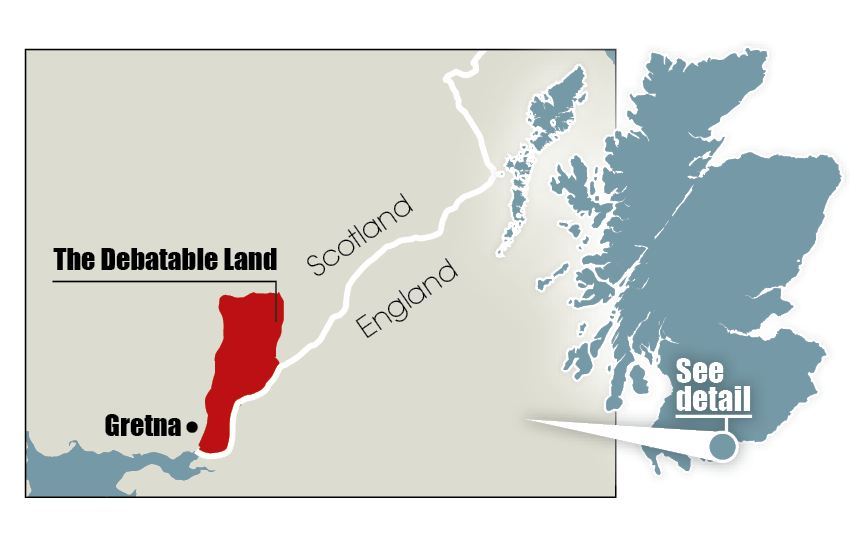

That’s the name given to the 50-square-mile area in the little bulge north-east of Gretna.

“I was moving back from Oxford and my wife Margaret and I found this place by chance,” said Graham, 59.

“It was previously owned by Nicholas Ridley, an MP in Margaret Thatcher’s government, and it still has a red panic button downstairs. The property is virtually surrounded by the Liddel Water and we own a part of the border.

“It’s a very isolated, scattered community with the closest main place in Scotland Langholm, about 10 miles away, and Longtown in England.”

Graham’s first startling insight into the land of which he only really knew the name came via a chance encounter with a farmer.

“I’d heard mention of the Debatable Land but I really knew little of it,” he said.

“The moment I knew I’d have to write a book was when I met this man who said they’d found something in front of the house, which went back centuries. When I asked what, he said it was a row of bodies.”

The bodies belonged to Reivers, the infamous horse and cattle rustlers, who launched raids on both sides of the border until the late 17 Century.

Graham said: “The Reivers didn’t go to church and they didn’t have graveyards so they buried the dead on their doorstep.

“I asked if he’d reported it and he looked around as if a policeman might be hiding somewhere and said he’d harrowed them under. He basically destroyed the evidence as he didn’t want any trouble.

“I knew then there was so much of a story untold.”

When he started his research, Graham learned that the Debatable Land had, for centuries, been a country in itself that was neither Scotland nor England, and was a very precise area.

For centuries no one was allowed to live on it and it was only to be used for fattening up livestock. It was unique in British history, not being common land and having no owner.

But when Scotland and England decided to divide the land between them around 1550, the peace came to a shattering, bloody end.

“A decree was passed making lawlessness legal,” explained Graham.

“Anyone in the Debatable Land was free to rob, burn, spoil, murder and destroy without any punishment.

“The thinking was that they’d kill each and other and then you could move in and draw a line to settle the border once and for all.

“However, they didn’t understand what they were dealing with and it became a very bloody place. But when I looked at detailed Scottish and English records I realised that the Reivers were very different from what I’d understood. They weren’t gangsters at all.

“Reiving raids were more like a rite of passage, few people were killed on them and it was actually a society that lasted a long time.”

When it was realised that the hopes that those in the Land would destroy each other wasn’t going to work, the Scots and English authorities took drastic action.

They decided to march in and clear it entirely in the late 16th Century. “Once it had been divided, the English solution was to round everybody up and deport them to Ireland.

“It was like a Lowland Highland clearance. They put them on ships to farm poor land across the Irish Sea.

“And the Scottish solution was to use the Duke of Buccleuch, who had been a Reiver, to pretty much massacre the population.

“He conducted a purge, slaughtering and drowning people, and cleared the land for Scotland.

“He was given letters by James VI stating that whatever he chose to do he wouldn’t be punished. He was actually rewarded and given land and money.”

Family names survived over the centuries, though, and many current residents can trace their ancestry back to those times, while the border is considered insignificant.

“Even though the accent changes very suddenly in an incredibly short distance, no one refers to someone having a Scottish or English accent,” said Graham.

“It is simply not an issue at all and it’s very much a cross-border community.”

Graham hopes that his book will lead others to discover this forgotten corner.

“People pass by on the way to the Lake District or up to the Highlands of Scotland because they don’t think there’s much here,” said Graham.

“It would make me happy if they knew that there is a lot more than meets the eye.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe