Forced to empty her childhood home after mum Marion moved to a care home, JULIE REA, 44, charts three bitter-sweet days of loss and memories.

Her empty chair felt like a smack in the face.

That would be where, as a teenager, I would find her every morning, my mum, Marion, at the blue formica table, with a cup of milky tea and a cigarette. When I was older, after I’d drop my two daughters, Eve, 13, and Lilly, 11, off at school, I’d bring us pancakes from McDonald’s, and we’d sit for hours having a blether. The kitchen was her domain, the engine room of our home.

My dad, Gordon, sadly passed away several years ago and mum, now 85, was recently diagnosed with dementia and had to move into a nursing home. Her own home, our home, had to be cleared.

As I turned the key in that familiar red front door in our high-rise in Clydebank – the door I’d walked through my whole life – the responsibility of it all felt daunting. How would I be able to box up almost four decades spent tethered to one place? How do you box up a life?

The kitchen would be the hardest part, I was sure. Mum’s trademark was her many, many fridge magnets – a Daniel Craig one was a favourite! – and, after I’d taken them all off, the fridge looked so unbearably stark that I actually stuck a few back on. There was a small cigarette butt in the ashtray on the windowsill and drawings my children made were still taped to the cupboard doors. The kitchen was hard enough but just the tip of the iceberg.

Every cupboard in my mum’s long hallway was haphazardly stacked, from floor to ceiling, with plastic bags. They were filled to the brim with Mother’s Day cards, birthday cards and Christmas cards. I read each one, there was so much love for her.

I sifted through each bag because, occasionally, I would come across important documents, like her birth certificate that I found stuffed between a bag of linen and cushion covers. At the bottom of one, I found pictures of my parents that they’d taken in a photobooth. It made me smile to see them like that; young, newly married, just goofing around.

My mum’s best friend was a woman named Margaret, who happened to be Marti Pellow’s mum. I found a school photo and baby pictures of Marti, a birthday card he’d written for her addressed to “Aunt Marion”. Growing up, there were many family parties at our house, everyone singing along to Abba and Queen. And, always, my mum at the centre, happiest when she was surrounded by her children and grandchildren, who all utterly adore her.

Certain things she kept – train tickets, movie stubs, magazine articles – seemed meaningless to me, but I wondered if they’d once meant something to her, enough that she chose to keep them? I wanted to ask her about them. But she will not remember now.

The weight of deciding what stayed or what was to be discarded felt overwhelming, but there were certain unexpected treasures. Inside a dusty wooden bureau were dozens of photographs of my mum as a teenager. In one of her at a dance with her older brother, Jim, she looked like Katharine Hepburn; slim, with curled, dark hair, wearing tailored trousers and crisp white shirt. Jim was wearing slacks and a smart cardigan, black hair slicked back with Brylcreem.

It felt like discovering gold. I never knew my uncle. He died, aged only 29, after being killed by a drunk driver. My mum never got over it. And, in a small, velvet pocket in the bureau – wrapped in a silk handkerchief – I found a faded note written in pencil from Jim to my mum and, beside it, a jagged newspaper clipping with the details of the crash that had killed him. I felt as though I was holding my mother’s grief in my hands, so out of respect I replaced the items, then took the bureau home.

On the second day, I tackled the largest cupboard in the hallway. It was so stuffed with things that I had to gingerly prise it open an inch at a time to stop an avalanche burying me. I started from the top shelf and, slowly, worked my way down. Toys, board games, hundreds of VHS videos, photographs, books, DVDs, vinyl records and – again – a bubble of crammed plastic bags.

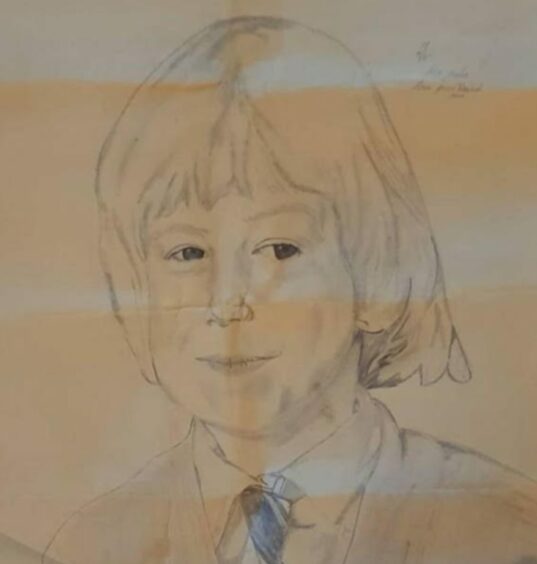

After many hours, at the very bottom of this cupboard, underneath almost 30 years of clutter, I found it. The precious item I had been searching decades for. A portrait that my older brother had once sketched of me.

David died, after a long illness, when I was 28 years old. He was incredibly artistic, and I remembered that, when I was younger, he’d drawn a portrait of me from my primary one school photo. We used to have it taped to the back of our living room door until, one day, it wasn’t there any more.

After he died, I asked my mum if she still had it, but she thought it must have been lost or discarded over the years. It always haunted me. And now, here it was, in my hands. There are so few items that I can touch that my brother left behind. It is beyond priceless to me.

A few years ago, mum moved out from the master bedroom, into what had once been my room. It had never been redecorated after I left home in my early twenties, so my elderly mother slept in a room covered with posters of Jim Morrison, Salvador Dali and Nirvana pinned to the walls.

I wondered why she’d done it. It was the smallest room and there was a large, black smudge of dampness spread up one of the walls. When we’d first moved in, I had plastered posters of Madonna and Bros everywhere and, rolled up at the bottom of a chest of drawers, I found those same old tatty posters.

I discovered hundreds of copies of my old NME magazines too, Melody Makers and Smash Hits, as well as a mound of Kays and Littlewoods catalogues and even a Kensitas Club Catalogue. I remembered our kitchen in the ’80s was practically decorated with every item in the magazine. Everything I unearthed, no matter how small, seemed to be charged with meaning and steeped in memories.

In a cabinet beside my mum’s single bed, I found a scrapbook. Inside there was newspaper clippings and articles…of me. Information about every story of mine that had been published, of writing awards or competitions I had won. I knew my mum was proud of me, of my writing successes, but I come from a working-class family, and we just don’t make a fuss about things like that. To know she’d secretly stored this away, blindsided me. I was so incredibly moved by it; my heart felt shredded.

On the third and final day, all the rooms had been emptied. Furniture and clothing taken to charity shops; objects all packed up. It looked heartbreakingly neat. Underneath a double bed in the spare room, I found a cardboard box filled with crockery and ornaments that had once belonged to my nanna. I remembered then, after my mum had emptied out her own childhood home, how exhausted she’d been. She said it felt like losing her parents all over again.

But my mum is, thankfully, very much alive. So what was I grieving? The answer came when, drained, I arrived home that evening and – as usual after visiting mum – my children hugged me and said, “you smell just like Granny’s house”. My hair smelled of my childhood home and I didn’t want to wash it, because I knew it would never smell like that again.

I left with only a bin bag stuffed with photographs and a few treasured mementoes. I thought I would need to keep every item to remember – the fun we had, the love, laughter, the parties, all the joy and pain, but I didn’t. Because I realised, they’re already with me, stored in my hard drive, forever.

I closed the red door for the last time.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson © Supplied

© Supplied

© Supplied

© Supplied