Ian Rankin was only 10-years-old when he first heard Let It Bleed. It took another 10 before he liked it.

Now, approaching the 50th anniversary of its release, he can only thank his big sister’s boyfriend for introducing him to the Rolling Stones classic at the family home in Fife… even if he hated it at the time.

“It wasn’t my kind of music, I was into T. Rex and pop,” said Ian. “Let It Bleed was grungy, it was difficult.

“I didn’t get a lot of the references at the time and it was quite a grim, seedy world on display. It seemed a world away from Cardenden.”

Over time, however, Ian began to appreciate the album and the band behind it. The Stones’ music crept into his writing; partly modelling his best-selling fictional detective Rebus on Stones founder member and fellow Fifer, Ian Stewart; making him a fan of the Stones; and naming his books after their albums, including Let It Bleed.

Before the seminal set turns 50 in December, Ian looked back on the times and tunes to understand its status as one of the best albums of all time.

“It reflected the times, the end of the 60s and the hippy-dippy idealism,” he said. “The Rolling Stones were there to see it turn a lot darker than people thought it would, from the peace and love of the hippies to Vietnam going wrong, the rise and birth of the serial killer and politicians being assassinated.

“The world seemed to be going to hell and a lot of that is reflected in the lyrics, as well as the sound. People say there is a lot of the blues in the album and the blues are often dark and about murder and mayhem.

“It’s quite a scary album to listen to and can take you to dark places.

“When I started writing about Rebus, I knew he would be a big fan, a fan of that earthy, bluesy nature of The Stones compared to The Beatles. The Stones were seen as the mavericks, the outsiders and the bad boys, of being dangerous in a way The Beatles weren’t.

“The ironic thing is it was The Stones who were the middle-class boys, while The Beatles were more genuinely working-class, but those roles were reversed when it came to the promotion of the bands.

“The message The Stones were giving out would have resonated with Rebus.”

Pianist Ian Stewart, who the Stones dubbed the Laird of Pittenweem, resonated with Rankin when it came to creating his Edinburgh detective.

Ian said: “That notion of being an outsider, of being on the outside looking in, and of being an integral part of something but never acknowledged as such. And, of course, Ian was from Pittenweem.”

The writer was in his 20s before he truly fell in love with the band and revelled in having a vast back catalogue to discover, but Let It Bleed remains his favourite.

“I must have bought the album about six times now – on vinyl, cassette, CD, a mono edition, the boxset and now there is a 50th anniversary edition coming out. At least it gives my son something to buy me for Christmas.

“You Can’t Always Get What You Want is an extraordinary way to finish an album. But the standout track for me is Midnight Rambler, which I think is terrifying in its relentlessness.

“The cover is memorable, too. This elaborate cake, which was done by a then-unknown Delia Smith, while the back cover showed the cake broken up.

“An image of something beautiful smashed to pieces. It felt like that was what had happened in the 60s, but I don’t know if that was what the band was going for.”

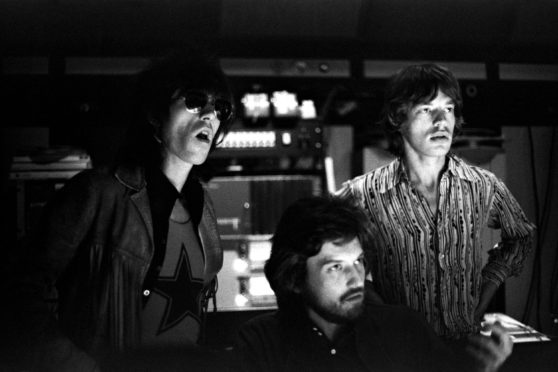

The Stones were in a state of chaos during the recording, which makes the output even more impressive.

“They were on the verge of collapse,” said Ian. “Brian Jones was floundering in a sea of drugs and was barely able to make it into the studio or play. That was when they brought in another guitarist, Mick Taylor, and Brian was sacked halfway through. Not long afterwards, he was found dead.

“The band was in a bad place and it could have been the end of them as a functioning rock band. They were falling apart at the same time as peace and love was.

“It’s to their credit they got something workable out of it, against the odds. There is something about them, they are survivors.”

Ian counts himself lucky to have met past and present band members.

“I’ve met Bill Wyman a few times as we have a mutual friend,” he said. “Then I met Keith when he launched his autobiography, as it was being published by my publishers and they asked if I wanted to come to London to meet him. We spoke for about 90 seconds, mostly about Ian Stewart.

“I met Charlie (Watts) at a memorial concert for Ian, where I was the MC, which meant I got to hang around backstage with Mick Taylor, Ronnie Wood, Charlie and Bill.

“Charlie is into watches and liked mine, so we chatted about that. And I was introduced to Mick [Jagger] at a photographic exhibition. Alan Yentob, who I’d worked with on a documentary, was also there and knew I was a big fan, so he grabbed Mick to have a picture with me. I have that photo as my screensaver.”

After missing a Stones gig when he was a student because he had an exam the next day, it was in an intimate setting where Ian eventually saw the band live.

“It was a secret gig at the London Astoria for fan club members, so there were only a few hundred of us there,” he explained. “And I saw them at Murrayfield last year, too. They were terrific. For a band in their 70s, they were really cooking and you could see their playing was exemplary.”

Considering they barely survived the making of Let It Bleed 50 years ago, why does he think the band continues to tour and record today?

“If you read interviews, it’s Keith who keeps them moving. He just loves playing and it’s Jagger who sometimes needs to be coaxed.

“But they’re a rock ‘n’ roll band, so what else are they going to do? Perhaps they feel that weight of tradition upon them, of being one of the last bands from a time in history that was the greatest period of rock ‘n roll music ever, and that’s what keeps them going.”

It was a groove. No doubt about it

Stones legend Keith Richards

Let It Bleed was released in December 1969 after what was, even for The Stones, a year of tumult, which featured the death of founder member Brian Jones.

As the album came out, the Stones played the notorious Altamont festival when a fan was stabbed to death by Hells Angels.

It was literally the end of the ’60s and, for many, the album soundtracked the collapse of peace, love and the hippy ideals.

Biographer Stephen Davis said of the album: “No rock record, before or since, has ever so completely captured the sense of palpable dread that hung over its era.”

Recording began for Let It Bleed in November 1968 and then sporadically between February and November of 1969 in London and Los Angeles.

It reached No 1 in the UK, bumping The Beatles’ Abbey Road off the top for a time, and number three in America.

Here, from his autobiography, Life, Keith Richards talks about three of the classics from the nine-song album.

Keith on: Country Honk

We were headed for the Mato Grosso [in Brazil]. We lived for a few days on a ranch, where Mick and I wrote Country Honk, sitting on a veranda like cowboys, boots on the rail, thinking ourselves in Texas. It was the country version of what became the single Honky Tonk Women when we got back to civilisation. It was written on an acoustic guitar, and I remember the place because every time you flushed the john these black, blind frogs came jumping out – an interesting image.

Keith on: Midnight Rambler

Midnight Rambler is a Chicago blues. The chord sequence isn’t but the sound is pure Chicago…That’s one of the most original blues you’ll hear from the Stones. The title, the subject, was just one of those phrases taken out of sensationalist headlines that only exist for a day. You just happen to be looking at a newspaper, “Midnight Rambler on the loose again.” Oh, I’ll have him.

Keith on: You Can’t Always Get What You Want

Mick and I thought it should go into a choir, a gospel thing, because we played with black gospel singers in America. And then, what if we got one of the best choirs in England, all these white, lovely singers and do it that way, see what we can get out of them. Turn them on a little bit, get them into a little sway and a move, you know?

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe