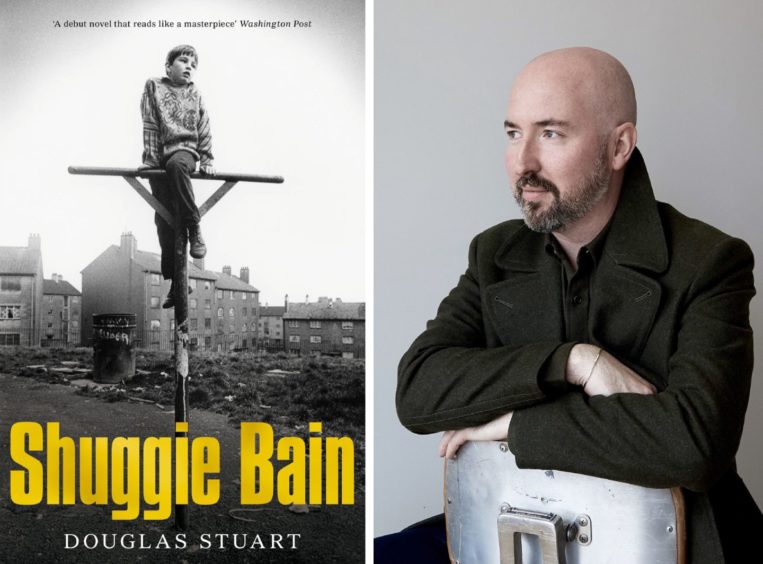

Speaking on Zoom, Douglas Stuart details a busy day ahead. After chatting to The Post about his follow-up to Booker-winning, life-changing debut Shuggie Bain, he is “going to do the messages then go to the pictures.” Despite more than 20 years in New York City, the award-laden author clearly still belongs to Glasgow.

He visits his home town often but most famously in fiction with his searing, heartbreaking but defiant debut, now followed by Young Mungo, another story charting a gay boy’s life in some of the grittiest streets in what, for many living there, can seem a very long way from a Dear Green Place.

Both novels draw on the alcoholism, poverty and violence that coloured Stuart’s own childhood but, he resolutely insists, should not be read as autobiography although the vivid reimagining of 1980s life on the housing estates of Scotland’s biggest city will have many readers wondering where fact ends and fiction begins.

A lot of Mungo and Shuggie – Stuart talks of his young heroes as if they’re real, and the habit is catchy – comes from his own experiences, he says, and he runs drafts by his sister, who still lives in Pollok, Glasgow. Yet, he is keen to stress, the boys are not him.

“My sister reads my work before anybody else gets to read it, and she understands it for the work of fiction that it is, even though it’s drawn from real life. I mean, Young Mungo was purely a work of fiction, nothing like that ever happened,” he says. “People do often confuse me and Shuggie as being very the same person and well, obviously, I was bullied, my mum died of alcohol. I grew up like that. I grew up in those places. We were that poor.

“But it doesn’t mean to say that the events necessarily happened to me. Some of them did, yes, but that’s fiction. No, I didn’t write a memoir.”

Shuggie Bain: Nicola Sturgeon salutes Scotland’s modern literary masterpiece

His debut novel was famously rejected by scores of publishers before going on to glittering, global acclaim, gaining rave reviews from fans ranging from First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to best-selling Jack Reacher author Lee Child. It would win the Booker Prize in 2020 when Margaret Busby, a publisher and chair of the judges, predicted it would become a classic, saying its young hero was an “unforgettable character” in “an amazingly emotive, nuanced book that is hard to forget. It’s intimate, it’s challenging, it’s compassionate.”

After his debut was shortlisted, Stuart posted online: “My own beautiful mother died of her addiction about 28 years ago. She was never voiceless – it was just people didn’t like to listen. I like to think she’ll be dancing in heaven tonight. All the lassies from the scheme will be there, cans cracked, Rod Stewart blaring.”

His hope of a party in heaven signals his nuanced feelings about alcohol. “I wanted to show with Shuggie Bain that, actually, sometimes drinking can be good, even when people are drinking too much,” he explains. “People have a good time. You know, there’s a lot of laughing. And then there’s also a lot of pain.

“I don’t think anybody who falls into addiction expected that for themselves. I don’t think that’s anybody’s plan and we don’t know what life’s going to deal us and we don’t know the troubles that will come or the loss of hope or the feeling of running out of options or the need to escape whatever it is that brings you to drink personally. We just don’t know.”

His novels may not be memoirs but Stuart, who left Glasgow to follow a career in fashion design in the US after graduating from the Royal College of Art, admits they do illuminate his difficult childhood and help him understand it better and, after a tilt at therapy, says writing helps more than any Manhattan psychoanalysis.

He says: “I didn’t find sitting in a room and telling someone my problems helped. I’m grateful for my creativity because I think that’s a good way for me to process things, and my writing brings me a lot of catharsis.

“But, funnily enough, it’s not because I’m sharing a trauma. It brings me catharsis, because when you create a fictional world of personal pain you have to think about the motivations of all the characters and why they would get there. So I came to terms with the stoicism of men and how hard men were when I was a kid, and why a mother with three beautiful kids might still drink herself to death.

“When I sat with that and I tried to just have empathy for my characters, that helped me deal with some of my personal pain.”

Like Shuggie, Young Mungo has a mother gripped by alcoholism and like his fictional predecessor is trying to grow through the cracks of a household held together with little more than hope of better things and love tempered by realism and low expectations.

Many of the experiences come from Stuart’s own life, such as his mum’s alcoholism, and his books chart the pain such addiction can inflict on those who are ill and those who love them.

The opening pages of Young Mungo sees the novel’s eponymous hero being shooed away on a fishing trip by his mum. She hopes Mungo’s softer edges will be whittled into something more masculine by two older men, who turn out to be the opposite of role models and pivotal to the novel’s building air of tension and uncertainty. It begins a pattern as, throughout the book, the young Glaswegian is insistently told to “man up” with potentially catastrophic consequences.

Much of the masculinity of the book results in the male characters feeling pressured into playing a part, too often leading to false bravado and sudden violence but it is not, the author says, intended to be a criticism of all men or masculinity.

“For me, we get to toxic masculinity too quickly, sometimes with my books, and people often overlook the spectrum of masculinity,” he explains. “I write about a pretty broad range of men in my books. I don’t fundamentally think masculinity is toxic.

“Sometimes men do bad things, but we’re getting to the point where men do something that is a mistake or a problem and it’s labelled too quickly as toxic masculinity. And we’re not taking enough time to really parse it. It’s a catch-all term, and people are just throwing everything in that bucket. Some of it is toxic, some of it does harm in society and is rampant but so much of masculinity is about performance. I was terrible at it, and terrified by it when I was a kid. Loads of men feel that way, I think straight men feel that way too. And you can’t break away, you can’t be seen to be saying, ‘Haw, this is daft’.”

Young Mungo is flecked with more violence than Shuggie Bain as sectarian gangs clash, stab and slash but like its predecessor it has a fraught but dizzying relationship at its heart. Shuggie’s enduring love was for his mother; Mungo stumbles into a tender doocot romance with a boy from the same scheme but a different religion.

The third book Stuart writes will probably continue what he calls a cycle of manhood and his aim is to build a tapestry of characters who would be able, in his imagination, to pick up the phone and talk to each other. But, he adds with a laugh, “just let me enjoy this one first. Young Mungo is a love story to Glasgow. There’s a lot of violence and deprivation but there’s also a culture of caring for other people, caring for someone who’s an alcoholic, or children of a neighbour.

“I think for Glaswegians that’s the right type of love because we’re not into big, blousey shows of emotion. Instead, what we do is we care for one another. Not all of us, some of us sow havoc but for the most part we have enormous compassion.”

As we talk about the building pressure young men face, Stuart is interrupted by a clank and a hiss. His malfunctioning New York radiator has piped up to join the conversation. He lives with his husband, Michael Cary, in an East Village apartment. He angles his laptop camera to the window, showing a fire escape and handsome brick buildings across the street where, judging from local realtors, apartments cost upwards of a million dollars, angry radiators and all. It’s very different from the tenements where he grew up but later, he says, he’ll “do the messages then go to the pictures” with Cary.

Stuart looks dapper for a morning Zoom call which makes sense considering he moved to New York aged 24 to work as a designer for fashion giant Calvin Klein. Looking your best was something on which his mum, even in the depths of her addiction, insisted.

“A lot of people think from the outside that if you’re working class we don’t have some kind of sense of pride,” he explains. “My mother had an enormous, outsized sense of pride. And we were always skint or always in money to the catalogue but we would never go to the front door without looking brand new every single day.”

“The years are rattling by in New York but I don’t make any sense anywhere other than Glasgow,” he adds. “Here, I’ve always got an accent but at home I’m just another person. New York just doesn’t really have a pub culture. My niece lives in Govanhill and The Laurieston is nearby, it’s a great pub. I can’t wait to go there and just hang out. It’s the best way to spend an afternoon.”

She fluttered her painted fingers and shooed him away. Go!

Young Mungo, Douglas Stuart’s second novel, tells of the hopes and heartbreak of the eponymous hero picking his way to adulthood on a housing estate in the 1980s.

Here is how the story begins:

As they neared the corner, Mungo halted and shrugged the man’s hand from his shoulder. It was such an assertive gesture that it took everyone by surprise. Turning back, Mungo squinted up at the tenement flat, and his eyes began to twitch with one of their nervous spasms. As his mother watched through the ear-of-wheat pattern of the net curtains, she tried to convince herself that his twitch was a happy wink, a lovely Morse code that telegraphed everything would be okay. F.I.N.E. Her youngest son was like that. He smiled when he didn’t want to. He would do anything just to make other people feel better.

Mo-Maw swept the curtain aside and leant on the window frame like a woman looking for company. She raised her mug in one hand and tapped the glass with her pearlescent pink nails. It was a colour she had chosen to make her fingers appear fresher, because if her hands looked younger, then so might her face, so might her entire self. As she looked down upon him, Mungo shifted again, his feet turning towards home. She fluttered her painted fingers and shooed him away. Go!

Her boy was stooped slightly, the rucksack a little hump on his back. Unsure of what he should take, he had packed it with half-hearted nonsense: an oversized Fair Isle jumper, teabags, his dog-eared sketchbook, a game of Ludo and some half-used tubes of medicated ointment. Yet he wavered on the corner as though the bag might tip him backwards into the gutter. Mo-Maw knew the bag was not heavy. She knew it was the bones of him that had become a dead weight.

Young Mungo by Douglas Stuart is published by Picador on April 14

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © PA

© PA