“What happened here never leaves me . . . it never will”

An inferno rages and acrid black smoke fills the air. Everywhere there are human remains, on the street, in gardens and hanging from trees.

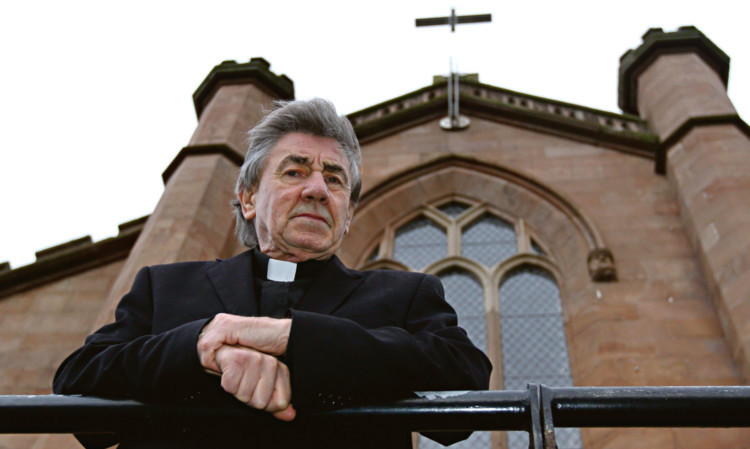

In Sherwood Crescent, which takes the full force of the impact, only one house is left standing Number 1. From it a solitary figure emerges. He is the local Roman Catholic priest, Patrick Keegans.

Shell-shocked, he tries to take in the scene but nothing can prepare him for the horror that unfolds. Standing over a 47-metre crater gouged out by the aircraft, he sees Number 13 is gone, obliterated by a section of wing and, with it, his friends and neighbours Maurice Henry, 63, and his wife, Dora, 56. He would later learn that there was nothing left of their bodies to bury.

Number 15 has exploded, killing John and Rosalind Somerville, both 40, and their children Paul, 13, and Lynsey, 10. Next door, Kathleen, 41, and Thomas, 44, Flannigan and their daughter Joanne, 10, also perish. From a neighbour’s garage their son Steven, 14, sees the fireball engulf his home. He and his older brother David, who was then living in Blackpool, are never to recover from their loss. Both die in tragic circumstances a few years later.

Mary Lancaster, 81, and Jean Murray, 82, are also killed.

“They were all friends,” says the priest, now Canon at St Margaret’s Cathedral in Ayr. “Little Joanne, Paul and Lyndsey had been delivering Christmas cards a few days before. They were lovely children.”

And in reliving that night, he reveals for the first time how, many years later, he prayed in prison with the man convicted of the bombing, Libyan Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi.

Cannon Keegans, 67, his deep voice slow and deliberate, paces himself as he speaks. Even after 25 years he is prone to breaking down. “I don’t dwell on it,” he says. “But what happened in Lockerbie never leaves you. It never will, until there are answers.”

He had just returned from Ayr with his 69-year-old mother who was spending Christmas at his home, and was upstairs hiding her present when all hell broke loose.

He recalls: “I heard the sound of a jet engine. Then there was a tremendous explosion. The whole house shook. I couldn’t move. I was worried about my mother downstairs. I thought, ‘This is when we die’.”

When he got to his mother he was relieved to find her safe but upset. He says: “I looked out and the whole street was gone. My house was the only one not on fire. I could smell gas and fumes and knew we had to get out. I put my mother’s scarf round her face and told her to keep her head down.”

They had been lucky. The pair were due to visit the Henrys an hour earlier, but delayed to watch the news. The last minute change of plan saved their lives. After getting his mother to safety he went back to the inferno.

“I was thinking of my friends,” he says. “I knew it was futile, yet I wanted to try. But there was no way because of the fire. There was smoke, rubble and remains everywhere.”

At that point a distressed elderly woman appeared and he and another man took her to safety. Canon Keegans recalls: “He told me the petrol station was burning. He said, ‘If that goes, we go too’. It was just 25 yards away. We had to leave.”

The priest took relatives, desperate for news of their loved ones, to the Town Hall where tea and blankets were handed out. For the rest of the night he walked the streets in an effort to find anyone who might just have made their way to safety.

He found no one.

“There was no panic,” he says. “Anxiety, tears, but no panic. There was a sense of unreality.

Cannon Keegans doesn’t believe divine intervention saved him. “It was simply not my time to die,” he says.

And when asked why God would allow such an atrocity, he points out that it is people “to whom God gave free will” who are to blame.

He believes forces other than Libya had a hand in the terror that rained down from the skies. For him, the attack on the Pan Am jet was in retaliation for the Iran Air passenger flight shot down in error by an American navy cruiser on July 3, 1988.

All 290 on board including 66 children perished.

And he believes Megrahi, now deceased, was a scapegoat. It’s a view shared by some of the bereaved families of British passengers on board flight 103, but one that has upset many.

He reveals: “I visited Megrahi in prison and we prayed together. We prayed for all the families. I believe he was innocent. That has made me persona non grata with a lot of the US families, but I have to be able to live with myself.”

Conspiracy theories are rejected by the authorities. Police detective John Crawford, who was part of a joint investigation between the then Dumfries and Galloway Constabulary and the FBI, has insisted the probe was thorough and the right man brought to justice.

Campaigners say the truth is yet to emerge, and the debate over the need for an independent inquiry rages on. But through Lockerbie’s darkest hour shines a beacon of love.

“Police set up a grid to map where each body was found and a friendship group was organised,” says Canon Keegans. “When relatives of the dead came to Lockerbie they were given a befriender to provide support and to take them to the spot where their loved one died. It was a marvellous response.”

Many friendships have grown as a result between the townspeople and the relatives of those on the flight, friendships that have spanned a quarter of a century.

Canon Keegans says: “Lockerbie looked towards others, not to itself after December 21, 1988.

“I’m very proud of the people of Lockerbie.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe