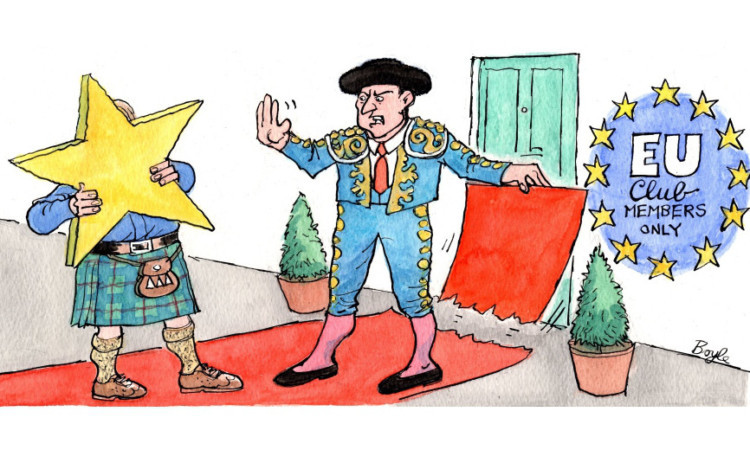

While an independent Scotland would gain entry to the EU, questions remain over when and on what terms.

Whatever the result of the referendum, the SNP will likely look back at the campaign and conclude they mishandled the issue of EU membership.

It may have become a touchstone issue anyway, but what really threw it into the spotlight was the hoo-ha over whether Alex Salmond had received legal advice on if, how and when an independent Scotland might get into the EU.

Salmond seemed to say in a TV interview in early 2012 that his Government had received legal advice telling them Scotland would sail into the EU. A few months and £20,000 in legal fees spent arguing over whether to confirm there was such advice later, Nicola Sturgeon admitted it didn’t exist. It was a low point for the Yes campaign and it’s clouded the issue ever since particularly unwelcome as the issue is extremely muddy to begin with.

What can be said with certainty is that Scotland wants to be in the EU. The latest poll by Sir Tom Hunter found 59% want an independent Scotland in Europe, 27% want out.

That’s more clear-cut than similar polls in the rest of the UK though they also usually show a majority want to stay in. England is not the uniformly Eurosceptic counter to Scotland’s embracing attitude towards Europe it is sometimes portrayed by the Yes camp.

What is also agreed by almost everyone is that an independent Scotland would get into the EU. The questions arise over how and on what terms.

As so often when it comes to the EU, the argument about how Scotland would accede is technical and bureaucratic. The Scottish Government say it would be allowed in under Article 48 of the EU. The UK Government say it would have to be Article 49. It’s only one digit but it makes a big difference.

Article 48 allows for current treaties to be amended with the agreement of all EU states. On paper, this is the easiest way in. And it could even fit with the Scottish Government’s independence timetable that ends just six months after a Yes vote in March 2016. The trouble is, it needs everyone to agree.

The Spanish for one are certainly sending out signals suggesting they would not play ball. If you think this independence debate is heated, you should see the one in Spain where Catalonia wants to break away.

Whilst London recognised the SNP’s mandate to hold a vote and granted it the necessary powers, Madrid takes a different approach essentially sticking its political fingers in its ears and ignoring the clamour from Barcelona where Catalans are to hold their own referendum in November anyway.

Similarly Cyprus, Belgium and Romania have their own issues with separatists. The Foreign Affairs Committee at Westminster noted the Scottish referendum caused “unease” in a number of EU capitals.

The UK Government says the Article 48 route is “utterly implausible”. They argue that should Scotland vote Yes, it is also voting to leave the EU and, as such, it would have to apply to get back in via Article 49.

Joining the EU from outside is much more tricky. Croatia was the last member to get in and the entire process took 10 years.

The signals from Brussels are mixed. Outgoing European Commission chief Manuel Barroso said it would be “extremely difficult, if not impossible” for Scotland to get back in and, in a letter to a House of Lords committee, said Scotland would have to apply to join “according to the rules”.

Incoming EC boss Jean Claude Juncker has said he will “respect the outcome” of the September 18 poll, but in a meeting with MEPs last week he reportedly added more ominously: “One does not become a member by writing a letter.”

The disagreement over Scotland’s route into the EU matters because if it did take the Article 49 route that would almost certainly leave Scotland outside the EU for a time. No matter how short, that would be disastrous given Scotland sells £11 billion worth of exports, currently without any barriers to that trade.

EU structural funds, of which Scotland has recently received more than its fair share, would dry up and farming subsidies would be suspended. The Scottish Affairs Committee calculated that falling out of the EU would cost Scots as much as £1,300 per household.

Only once a route in was agreed could negotiations over terms begin. Britain, due to its sheer size, has got away with all manner of rule-bending down the decades. If the UK wants an opt-out, the rest of Europe at the very least must listen because we bring such heft to the European free trade project.

Scotland’s voice would not carry as far. Britain pays billions into the EU, but unlike other countries we also get cash back a rebate currently worth in the region of £5 billion. The rebate was arranged because the UK doesn’t benefit from agricultural subsidies in the way other EU nations do. The Scottish Affairs Committee claims it’s currently worth £900 per Scottish household. The Scottish Government say they would negotiate for a share of the rebate that’s been agreed until 2020. That might work, but after that date, it’s unlikely Scotland would continue to receive a rebate.

EU contributions are worked out according to the size of a country’s economy and linked to VAT returns. EU rules say the minimum amount of VAT should be 5% on everything, but because the UK negotiated an opt-out, food, children’s clothes and books remain VAT free here. If independent Scotland failed to broker a similar exemption the price of those goods would go up.

Then there’s the big figures structural funds that the EU shares out to help boost the poorest areas and the subsidies farmers receive under the notorious Common Agricultural Policy and fishermen under the Common Fisheries Policy.

Westminster has poured structural funds into Scotland in recent years. It’s scheduled to get £186 million extra before this budget period runs out in 2020.

Cynics, especially those in the north-east of England who reckon they’ve been short-changed, suggest that’s been a political decision driven by the referendum. They’re probably right and, if Scotland votes No, it may well see its share of UK structural funds slashed after 2020.

The CAP has been drastically reformed since the days when it led to fabled wine lakes and butter mountains in Strasbourg, but it does protect farmers from the worst of the economic weather and consumers from erratic price changes.

The UK also has an opt-out from the Schengen Agreement on free travel. Scotland would have to agree the same terms with the EU if it wanted to keep borders with England and Northern Ireland open. It may manage that, but at this stage there’s no guarantee. Fail and Scotland would have to sign up to Schengen ensuring all Europeans could flock to Scotland.

One opt-out that Scotland currently has would almost certainly have to go. English students are charged to study at Scottish universities while those from the rest of the EU get free tuition the same as Scots. If Scotland became an independent member of the EU, it would not be allowed to discriminate against a fellow member state in such a way. English students would get free tuition, the Scottish Government would get a hefty bill and they haven’t explained how they’ll pay it.

The issue of how and when an independent Scotland would get into the EU is one of politics versus economics. Despite the objections of places like Spain, economics would most likely win ensuring Scotland would get in.

For all that Strasbourg and Brussels seem distant politically, the terms of entry would have a direct impact on everyone in Scotland’s life and pocket.

Scotland could get itself a very good deal. But it may not. For now, like so many independence issues, it is uncertain.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe