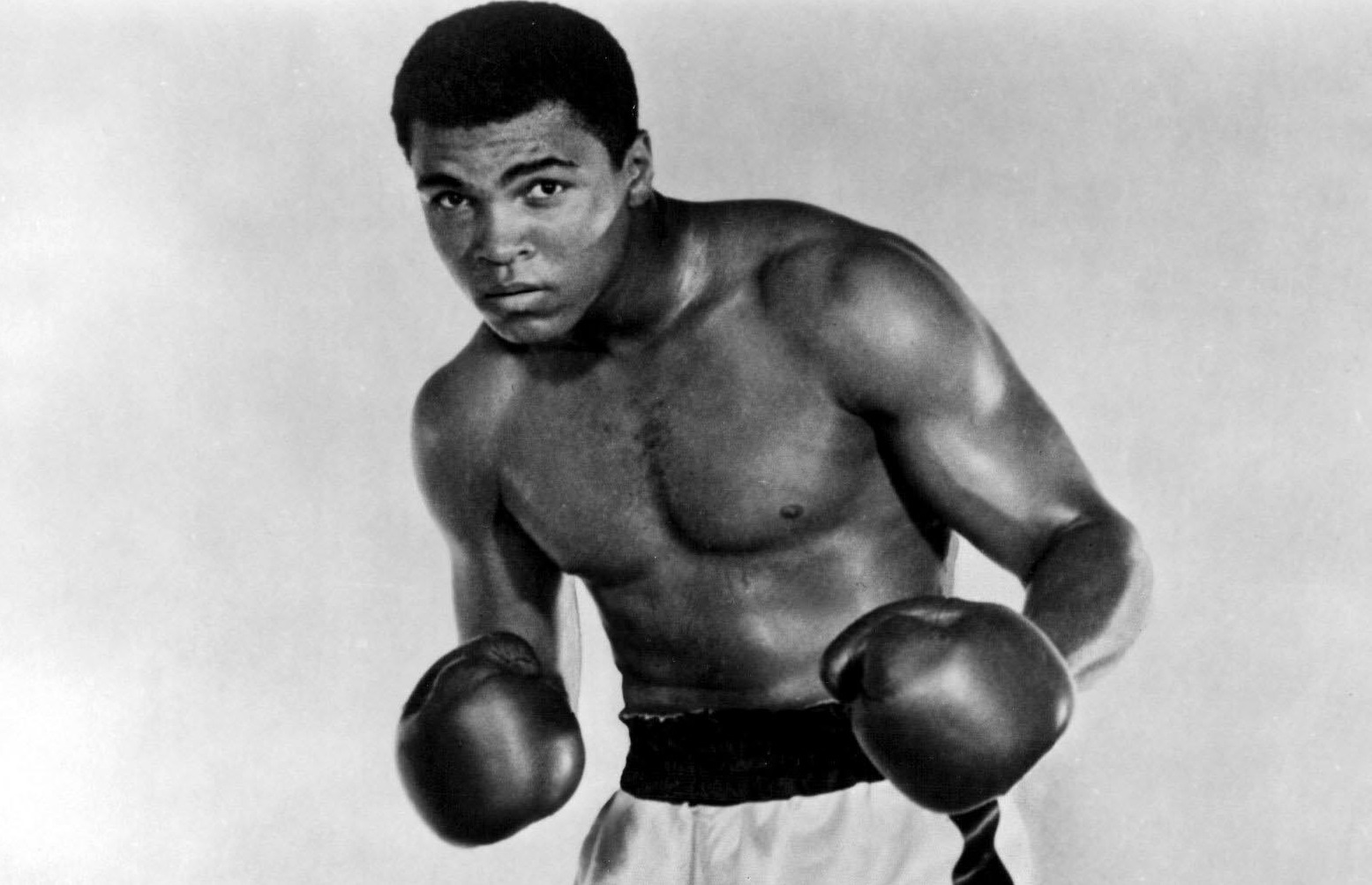

YESTERDAY was unusual because it was the first day I can remember when Muhammad Ali wasn’t around.

I was in Primary 1 at Harthill when he defeated Sonny Liston to become the mouthiest heavyweight champion in history.

I was four years into my journalistic career when I wrote the report of his final contest for this newspaper.

Autobiographies are like sandwiches. The bread consists of the before and after part of the subject’s professional career while the meat is what they did to make them famous.

With Ali, though, it was never quite as simple.

The struggles he endured with Parkinson’s Disease for 32 years were heroic in themselves as he fought an opponent he could not beat but refused to back down to.

There will be critics who claim that boxing is to blame and that the punishment he took (in the three fights against Joe Frazier and Ken Norton, against George Foreman, Earnie Shavers and Larry Holmes) contributed to his condition. And maybe they did.

That, though, is to miss the point. Boxing did not destroy Muhammad Ali – it created him, gave him purpose, meaning and a platform which helped him to change his world and that of millions of others.

If it hadn’t been for boxing, social media would not have been inundated by spontaneous outpourings of sadness.

If Cassius Clay had never climbed into a ring he may still be alive today but no one outside his immediate family would know.

As it is, he lit up the 1960s and 1970s with his brilliance and his wit, bamboozling opponents and interviewers alike.

Watching him on television – whether in the ring or on Michael Parkinson’s chat show – he brought colour into our black-and-white television set.

He wasn’t just larger than life, he was everything you could possibly want to be. Smart, funny, handsome and talented – there was nothing not to like for any boy growing up in a Lanarkshire mining village.

Or anywhere else, for that matter.

READ MORE

Muhammad Ali: World unites in grief after death of The Greatest

Tommy Gilmour Jr and Dick McTaggart on their meetings with Ali

You can usually tell something about people’s characters by the athletes they choose to support in sport’s great rivalries.

John McEnroe v Bjorn Borg, Steve Ovett v Sebastian Coe, Jimmy White v Steve Davis, for example. Anyone who wanted the first-names to win was likely to be someone I’d want to spend time with, the others not so much.

However, while Muhammad Ali v Joe Frazier was a truly titanic and defining rivalry, I don’t remember anyone in my school playgrounds who ever wanted Frazier to win. It was different in America, of course, and not always for sporting reasons.

Indeed, even at the time of that terrific trilogy, I felt Ali had overstepped the mark in his abuse to Frazier, who was an honest and worthy champion. Ali belatedly accepted that but Frazier was, understandably, bitter towards the end and never forgave or forgot.

For the most part, though, Ali was a joy to behold. The crushing disappointment of his defeat by Frazier in their first meeting was almost worth bearing when he slayed George Foreman in the Rumble in the Jungle.

The tragedy which befell him in his final decades was thrown into sharp relief by his hilarious appearances on Parkinson, when he would have his host doubled up with laughter.

His final years were a roller-coaster ride for fans as he raged against the dying of the light. Watching him go through the motions against lesser rivals and then come close to falling off the tightrope against more talented opponents was stomach-churning.

Watching him box on for 11 rounds with a broken jaw against Ken Norton was almost as painful to watch as it was for him to endure.

I remember cursing his lazy performance when he lost to Leon Spinks and then cheering like VE Day when he got his act together in the rematch to become the first man to become heavyweight champion for a third time.

Then there was the long, drawn-out finale. A challenge to his successor, the impressive Larry Holmes, which should never have been allowed to happen.

He bowed out, one month short of his 40th birthday, in December, 1981, with a points defeat against Trevor Berbick. It was my first-ever fight report for this newspaper.

If ever anyone was born to have a long and distinguished career as a fight analyst for television, it was Ali. Unfortunately, his illness deprived him – and us – of that opportunity.

Even so, he continued to raise money for charities and was always willing to meet with an adoring public.

On November 19, 1993, it was my turn. He was doing a book-signing tour and came to Waterstone’s in Glasgow.

Deploying my native cunning, I arranged a competition for the newspaper I was working for at the time, with signed copies going to two lucky winners.

That allowed me to jump the queue to shake the great man’s hand, have a couple of books autographed (the one he was promoting plus another I’d brought along) and to have my photograph taken with him. These remain my most cherished pieces of sporting memorabilia.

Ali stayed for two hours longer than he was supposed to in order to accommodate every one of the thousands of fans who queued to see him (including Ally McCoist and world flyweight champion Paul Weir) before leaving for more of the same in Edinburgh.

Some heroes don’t let you down.

Unsurprisingly, The Greatest belongs to that exclusive club.

READ MORE

Scot Ken Buchanan on being the only man to push Ali into second place

Ali deserves the credit for bringing money into boxing, says Scots former champion Jim Watt

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe